Heidi Sopinka is likely one of the rare people that can be called a jack of all trades, and a master of all. The 46-year-old mother of three boasts a resume that includes stints as a bush cook in the Yukon, a helicopter pilot, a travel-guide writer in Southeast Asia, a magazine editor and writer, the co-founder of cool-girl-approved Toronto fashion brand Horses Atelier, and now, a novelist. Having grown up on a farm in Ontario, riding horses before school, Sopinka has long been fascinated by animals and all things wildlife.

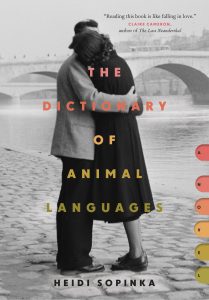

Her new release, The Dictionary of Animal Languages (Hamish Hamilton Canada), tells a tale of love, grief, animals, and art, through the story of a woman named Ivory Frame at the ages of 19 and 92. After studying art in interwar, avant-garde Paris, the novel’s heroine becomes a renowned painter. But she loses everything when WWII breaks out, and she devotes the rest of her life to creating a dictionary of animal languages, hoping to bridge the barrier between humans and the natural world.

The Dictionary of Animal Languages is out now, and I highly recommend you snag yourself a copy. But until then, read on as we talk books, fashion, nature, and fearlessness.

How did you become a bush cook?

I studied English Literature at McGill University, which was great, but I don’t highly recommend it if you want to be a writer. So, I left there deciding I was going to do something really practical. So I spent a summer cooking for forest firefighters in the Yukon. We got flown into fires in the middle of nowhere and I felt like, “why are they even trying to control these fires?” It felt so remote. It was really an amazing thing to see. The cooking part was fine. It was like cooking for giants, making huge portions for like 60 people in the middle of nowhere.

So from literature to helicopter flying – that’s a complete switch.

Well, it did, and it didn’t. It was a bit of – like anything in life – a very strange pathway to get there. But I flew in Texas and got into a really specialized bush training program. I got into the program, which was very exciting, but then they cut the funding. So, it cut that career short. It was very expensive to constantly keep up with my training and everything. At that point, I started my masters out west in literature and then I dropped out and used the rest of my tuition money to fly to Southeast Asia. I became a travel guide writer for a British publisher there. I got to go from place to place and write about it. In a nice way – it wasn’t like those guides where you’re listing facts. It was giving a picture of Thai food or the Balinese ancient form of Hinduism…like something very fascinating to me. That was really lovely, and when I first felt like a writer.

Is that when you came back to Canada?

Yeah, I came back and sort of debated getting into book editing, and it just seemed so difficult and small. So, I decided I wanted to get into magazines, so I ended up working for Azure, a design and architecture magazine, and then from there worked for other magazines and wrote freelance and edited for magazines.

What was the inspiration behind the idea of the animal language dictionary?

I’m really interested in language and communication, and I guess I felt like the main character, Ivory, is a solitary figure, but she has this sort of intimacy with animals. It’s her life’s work. And she exists in this sort of wordless place. But I think the notion that if you can communicate, you can understand something or someone. So, she takes it on herself to make a dictionary of all the animals in order to stop extinction – if we understood them, we would revere them, and essentially change the world order.

You must have had to do a lot of research on animals for this.

I mean, I did, and I didn’t. I definitely have some weird information that I gained. Oddly, I started looking into people that study animal communication, and there are such things as acoustic biologists, which I had no idea existed. In fact, there is a woman in Africa, who has for 30 years been compiling a dictionary of elephant languages. I had no idea such a thing existed. I sort of made it up and then realized it’s actually a thing. So that was interesting. I did a lot of reading. I re-read Silent Spring and I read a book by Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and people that have spent their lives devoted to animals. But I actually did a lot of reading too on the surrealists in Paris because that’s the other storyline. When the main character is 19, she’s in Paris in the ‘30s before the second world war. So, I definitely looked a lot at the surrealists and their artwork and their performances and their strange parties in Paris.

When did you start your clothing line, Horses Atelier?

So I guess it was in 2012. My friend Claudia Dey, who is also a novelist, and I were pushing our strollers – we both had babies at the same time – and we were both struggling trying to write, and finding it really hard with young kids, and we suddenly, within a few blocks, hatched a plan to use our love of design and clothing to start a label. We had our name and first few designs within a few blocks. We had this hilarious notion that we were going to make big money as designers and then we could make our weird art books on the side. We didn’t realize that it’s maybe the one industry that’s worse than publishing in terms of being competitive and difficult to make money at [laughing]. We had weird focus, I guess, and we just sort of went for it. It was a lot of hard work. Now when we look at it we’re like “wow, what were we thinking doing that with young kids?” But it was, and it still continues to be, a really nice counterpoint to writing, because it’s a visual world and it’s really social.

What’s your role in Horses Atelier?

I guess I’m the co-founder of it and the co-designer, so with my partner Claudia we come up with the designs of each collection and manage the whole operation as a business.

How would you describe the style of Horses Atelier clothing?

I guess we sort of always said it was like Japanese classicism meets Parisian chic. We love this notion of this woman riding a bicycle like you’d see in Paris or something. So, it’s sort of simple and timeless with a really amazing fit. And the fabric has to feel really great on your body, which is why we only use really nice silks and wools from Italy and cottons from Japan, and that sort of thing.

You’re also personally a very stylish woman. Toronto Life referred to you (along with your Horses Atelier co-founder Claudia Dey) as one of Toronto’s best dressed.

[Laughing] they haven’t seen my writing outfits.

How would you describe your personal style or aesthetic?

I think I’m pretty minimalist, but I love Victorian blouses, and I love silk kimonos, and obviously our clothes are a big part of what I wear. And I usually have some sort of vintage element, and something handmade I love too. My grandmother on my dad’s side – my dad is Ukrainian – and I have some of her Ukrainian dresses and blouses. It’s totally my peasant stock. I love that beautiful, handmade vintage piece as well. So, I kind of swing between both things, and I like the Studio 54 silk jumpsuits at night and then something more everyday and handmade for the daytime. I always am wearing jeans. It’s a problem.

Do you have a particular outfit or garment from Horses Atelier that is your go-to?

I would definitely say one of our work suits. Probably our Field Suit. We made it because we like to wear one thing. You don’t have to think about what your pants are. You just put it on and it’s one thing and you go out the door and you can wear high tops in the day and you can change and put heels on if you have to go out at night and it’s just comfortable. I can’t stand things that are really tight. I want to rip it off at the end of the night.

I’m also curious about the name that you chose – Horses Atelier. What does it mean to you? Is there a connection to you having grown up around horses?

It’s sort of a lot of things. For us, initially, I had just given the Patti Smith memoir – the Just Kids one – to Claudia for her birthday, and we sort of thought of Patti Smith and her album “Horses,” and then “atelier” just came up because we kept saying: “We’re horses.” And then everyone would laugh. It sounds like we’re animals [laughing]. So, we tacked it onto the end, because we like that it was the French word for studio. I mean, I have a relationship with horses. My mom had horses, and they live on a farm still, but we realized a lot of women have relationships with horses. Like whether they rode them or even were exposed to them or not, they sort of evoke a strong emotional response, which is great. We didn’t expect that.

In terms of all the things you’ve done in life, are there things that you were afraid to get into?

Well, flying was definitely one. I was young enough to not really notice my mortality, but my mom, who has a terrible fear of flying, was very nervous about me doing that. I hadn’t really thought of that until I actually was up in the air by myself, and I remember my hand getting sweaty because I was a bit nervous that it was my first solo flight. I remember the controls kind of slipped and I nose-dived a tiny bit and I was like “Oh God, I actually have my life in my hands – literally.” And that was the first moment I thought of that, weirdly. I hadn’t thought of that the whole time until then. And with writing, there’s this certain fear that you can’t do it. But again, I feel like the thing I’ve learned is you just do it. You might do it badly, but eventually you’ll get better.

Are you able to give any hints on your next novel that you’re working on now?

Well it’s also a group of artists, but there’s oddly a love triangle and possibly a ghost story within it. It’s set in the ‘70s. I started finding all these weird fringed and ruffled kind of things in second-hand stores and my friend Claudia was like “maybe you’re dressing for your next book.”

Main image of Heidi Sopinka by Arden Wray. This interview has been edited and condensed.