Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

If you were a kid in the 1980s, you probably, at some point, had a Cabbage Patch Kids doll. The soft-bodied baby-like dolls, each of which came with its own “adoption certificate,” were a worldwide phenomenon that reportedly generated about $2 billion in sales throughout the decade, while garnering endless media attention and controversy, and causing a series of violent customer outbursts and riots in numerous retail stores across North America in the fall and winter of 1983.

If you turn over the doll and look on the left bum cheek, you’ll find Xavier Roberts’ signature. Xavier Roberts was born in Cleveland, Georgia, in October 1955; he is best known as the father of the Cabbage Patch Kids and the creator of a toy phenomenon that had never been seen before. However (spoiler), Roberts didn’t actually invent the dolls…although he took credit for them until an ugly lawsuit began at the height of the dolls’ popularity. But you might not know about that.

You also might not know that a Kentucky artist named Martha Nelson Thomas originally invented the cute little dolls, but her design was stolen and transformed into a multibillion-dollar franchise that dominated the decade.

Here’s the not-so-cute history of the Cabbage Patch Kids dolls from the very beginning.

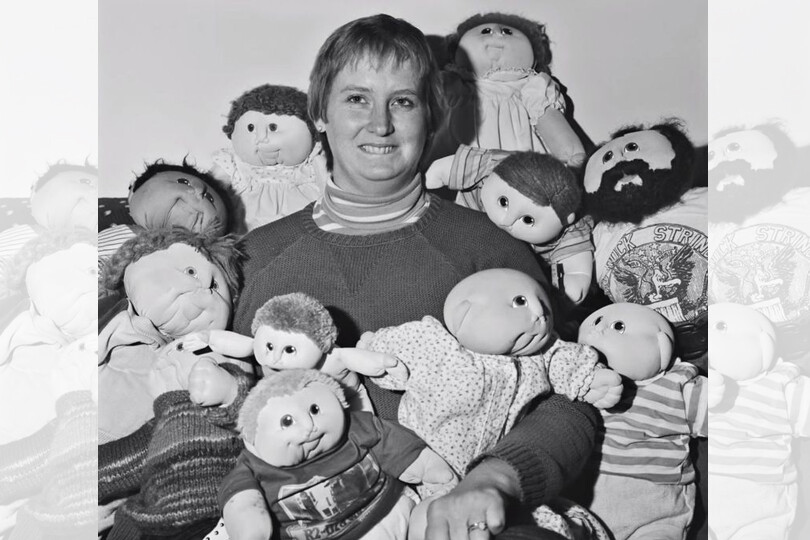

Doll Babies and Little People

The original Cabbage Patch Kids dolls were invented by craft artist Martha Nelson Thomas, who started working on her “Doll Babies” – her name for the line of toys – while she was still in art school in the early 1970s. Thomas experimented with soft sculpture to give her dolls a more realistic, three-dimensional look, and was “flat-out reinventing the doll,” her friend Guy Mendes told Vice in 2015. “The doll babies were her brood. She shopped for them. She dressed them. They were expressions of her.”

Thomas, who hand-stitched every doll she made, sold her stretch-fabric Doll Babies with their overly round faces at various craft fairs throughout Kentucky in the ’70s, where people could “adopt” the one-of-a-kind creations, which came with a unique “birth certificate” and “adoption” papers that Thomas had created.

In 1976, a young art student by the name of Xavier Roberts met Thomas at a craft fair, and was taken by the dolls and their sculpted faces. Roberts began purchasing the Doll Babies from Thomas to sell at a profit at a Georgia State Park gift shop where he worked. After several dolls were sold, Thomas decided to stop supplying her handmade dolls to the shop due to a dispute over pricing with Roberts and also because she was concerned he might take the idea away from her.

With his supply of Doll Babies cut off, Roberts decided to create his own version of the dolls. In fact, he wrote Thomas a letter stating that if he couldn’t sell her dolls, he would sell something like them.

Roberts was a skilled artist in his own right, so with the help of artist Debbi Moorehead, he began making soft sculpted dolls himself, which he called Little People (the name was to change later). Each one of his creations was completed with a hand-signed “Xavier Roberts” signature on the doll’s bum that was done with a felt-tip marker. But that wasn’t the only difference; Roberts modified the look of Thomas’ Doll Babies, as well as the birth certificate and adoption papers, sufficiently to get a copyright. He then began selling his Little People dolls at arts and craft festivals, telling potential customers his dolls weren’t for sale, but could be “adopted.”

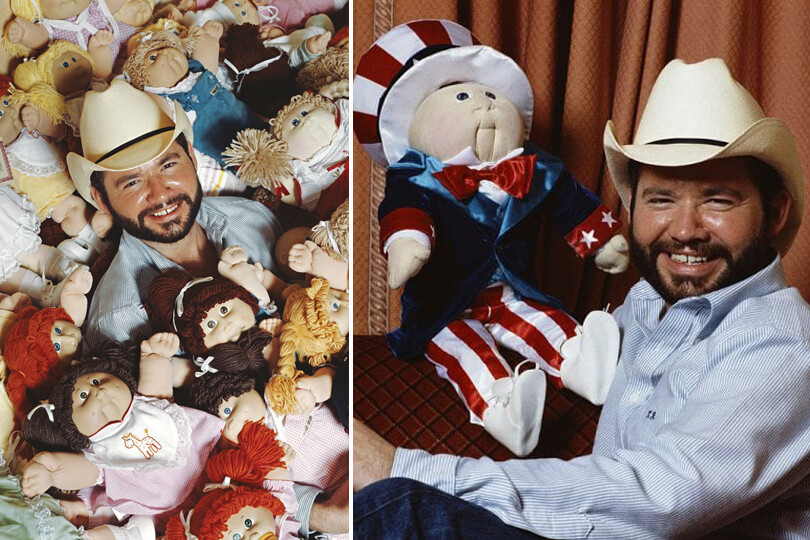

In 1978, Roberts formed the Original Appalachian Artworks, Inc. company with a handful of his friends, who would later became employees. Together they renovated an old building in Cleveland, Georgia, and turned it into a clever little shop that would become known as BabyLand General Hospital. It was an interactive experience that looked like the inside of a hospital, with nursery rooms filled with Roberts’ initial handmade soft sculpture 16-inch Little People dolls and their signature “certificates of authenticity” (not yet called adoption papers). Instead of sales clerks, Roberts turned his employees into nurses and doctors, giving them uniforms.

Thomas found out about Roberts’ new dolls by chance. A woman who had purchased one of his dolls in the Georgia area approached Thomas at an art fair to congratulate her on selling her dolls at the Atlanta Airport. The lady showed Thomas the doll, and that’s when she realized how completely Roberts had stolen her Doll Babies concept.

Birth in a cabbage patch

Roberts’ soft sculpture Little People dolls were a local hit in the late ’70s, and by 1981 they were being written about in magazines and newspapers. By the following year, Roberts and his friends at the BabyLand General Hospital were unable to keep up with the orders and Roberts licensed the dolls – which were now to have round vinyl heads – exclusively to Coleco for mass-production under the name Cabbage Patch Kids (the Xavier Roberts signature remained on the bum, although they were no longer signed with a felt-tip marker). Coleco began selling the dolls for US$35–45.

The dolls were now being mass-produced, but thanks to advances in manufacturing technologies, no two dolls were ever the same. Computerized machines were able to create infinite randomizations by varying several aspects of the dolls, including hair, dimple locations and skin tone. Their names were also unique.

The Cabbage Patch Kids came with a new origin story that was printed on every box. “Xavier Roberts was a 10-year-old boy who discovered the Cabbage Patch Kids by following a BunnyBee behind a waterfall into a magical Cabbage Patch, where he found the Cabbage Patch babies being born,” it read. “To help them find good homes, he built BabyLand General in Cleveland, Georgia, where the Cabbage Patch Kids could live and play until they were adopted.”

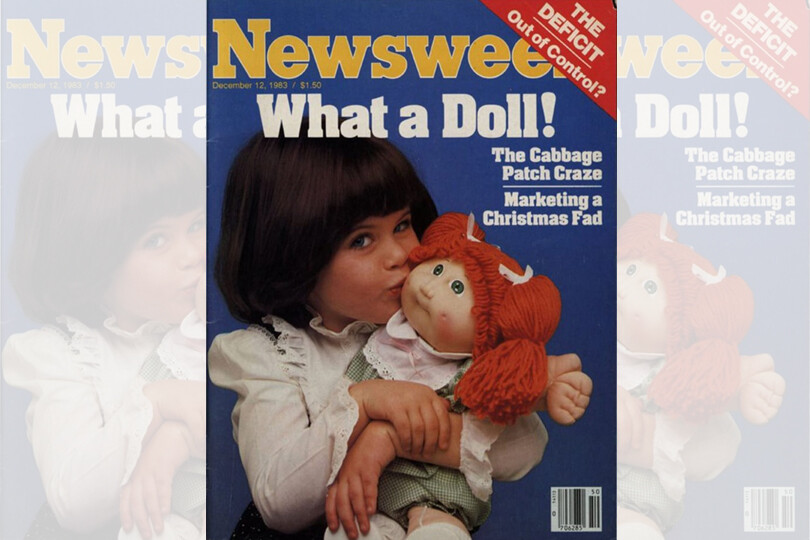

Coleco kicked off a massive marketing effort in June 1983 at the Boston Children’s Museum, where it held a mass Cabbage Patch Kids adoption event. The media ate it up, and the Cabbage Patch Kids were quickly featured everywhere, including a cover story in Newsweek before the end of the year. Nobody, including Roberts or retailers, had any idea what would happen next. But by the end of the year Coleco couldn’t keep up with the demand for the doll, creating a buying frenzy just before Christmas 1983.

Christmas wish list

The consumer response was so great, Coleco cancelled all of its advertising as they tried to keep up with demand – shipping a doll-industry record of 3.2 million dolls.

By November 1983, Cabbage Patch Kids were so scarce and so in demand that parents were willing to camp outside of local toy stores or drive hundreds of kilometres just to buy one. Most stores at the time typically only stocked between 200 and 500 dolls, but there were thousands of eager customers, which meant that frustration was brewing. Some stores held draws to keep things orderly, while others left things to be a free-for-all. Not surprisingly, a frenzied resale market began, with desperate gift givers willing to pay big bucks to get their hands on the dolls. Then mini-riots began to break out in stores across North America.

The so-called Cabbage Patch Riots of 1983 were the precursor to every violent Black Friday to come, but unlike most Black Friday sales, the Cabbage Patch Riots had parents battling it out fearful of potentially ruining their child’s life by not having this very special doll on Christmas morning.

Archival videos of news stories (which are readily available on YouTube) show pandemonium at stores in the United States and Canada, with boxes containing Cabbage Patch Kids being flung about. There were violent occurrences in major retail stores like Sears, J. C. Penney, Wards and Macy’s, with the nightly news reporting on incidents of hitting, shoving and trampling – not to mention bloody noses, broken arms and broken legs.

At a Simpsons department store in London, Ontario, a shopper named Bonnie Jeffries described the chaos she witnessed when she went looking for a doll in November. “I just, I couldn’t believe it – people yelling, screaming, knocking over merchandise, boxes flying, people crying because: ‘I didn’t get one,’” Jeffries said. “Like, someone grabbing two and three [dolls] and then someone complaining to the manager because ‘they got two and three and we didn’t get any’ and all this. I couldn’t believe it.”

At a Zayre department store in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, a riot broke out, with a store manager grabbing a baseball bat to protect himself. “This is my life that’s in danger,” William Shigo was quoted as saying in the New York Times. At a Hills Department Store in Charleston, West Virginia, 5,000 parents staged a near riot trying to get their hands on the dolls and left manager Scott Belcher describing the Christmas mob to the media: “They knocked over the display table. People were grabbing at each other, pushing and shoving. It got ugly.”

Two disc jockeys in Milwaukee even wisecracked that a load of the dolls would be dropped from a B-29 bomber to people who held up catcher’s mitts and American Express cards; two dozen believers actually turned up at County Stadium, braving a wind-chill factor of –2°F (19°C) to try and catch a doll.

Two years after the riots, Roberts reflected on the violence surrounding the dolls to the Chicago Tribune, saying he had thought about it endlessly but hadn’t come up with an answer that suited him. “Gosh, I don’t know,” he said. “I think it was a good product. I think we all worked very hard. I think the timing was right. Video games and all the plastic and battery-operated toys were around, and here was something you could just sort of pick up and love. I mean, it didn’t do anything.”

After the riots

The success of the Cabbage Patch Kids went beyond the 1983 Christmas riots. The year was obviously a massive success for Coleco and the Cabbage Patch Kids – by the end of 1983, almost three million of the Cabbage Patch Kids had been sold and adopted – but that was small potatoes. In 1984, 20 million Cabbage Patch Kid dolls were purchased, and sales of Cabbage Patch Kids dolls and branded merchandise (children’s apparel, bedding, sleepwear, lunchboxes, Thermoses, books and countless other products) generated an industry record of $2 billion in retail sales across North America, Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

All that made Roberts a very rich man and a darling of the media – again and again, he told the story of how his magical babies were born. The world couldn’t get enough of Xavier Roberts. He was living in a mansion with a fleet of luxury cars that included three Mercedes-Benz, two Jaguars, a Rolls Royce, a Corvette, a BMW, a van and a Jeep. He landed on a list of the 10 Most Eligible Bachelors in the World. (“Big deal,” Roberts sniffed about that to the Chicago Tribune in 1985 as he prepared to launch a line of country-inspired toy bears called the Furskin Bears. “Boy George was on it, too.”) He received proposals and propositions from smitten women across the globe (“They say, ‘If you’re ever in Boise, stop by for some champagne’”).

Thomas and her husband, Tucker Thomas, watched as Roberts continued to profit from her Doll Babies idea. With the encouragement of friends, Thomas had sought legal advice in the late ’70s from a lawyer named Jack Wheat, who worked for Legal Aid, because that’s all she could afford. Thomas’ lawsuit was originally filed in 1979, but it took six years of wrangling for the case to go to trial.

Up until this point, Roberts had claimed – in hundreds of magazine and television interviews throughout the years – that he was solely responsible for the creation of the Little People dolls and the Cabbage Patch Kids dolls. He had always claimed that the inspiration came to him when he was an art student, and that before the Little People dolls he had been making soft sculptures using quilting and hand-stitching techniques.

Roberts’ story changed when both parties finally became embroiled in a bitter legal battle to claim ownership of the idea for the dolls. It went to trial in 1985 and Thomas argued that Roberts had stolen her idea completely, that the Cabbage Patch Kids were copies of her Doll Babies. The problem was that Thomas didn’t have any documents to prove her claims, and she hadn’t copyrighted her concept.

“The theme of his defence was ‘Yes, I was inspired by Martha, but I changed the design and came up with my own design,’” Wheat told Vice in 2015. “It’s not the law right now but, in those days, before you could copyright a product, you had to actually put a copyright notice on it – ‘C’ with a circle, or the word ‘Copyright.’ She thought that took away from the Doll Babies being children. Therefore, she could not copyright her design.”

Because Thomas had never copyrighted her Doll Babies, she was fighting a losing battle. But then things changed.

“At some point in the middle of the trial, Xavier Roberts’ counsel approached me and said ‘Let’s discuss settlement,’” said Wheat. “And that day, the case settled.”

While some have claimed that Thomas “never saw a penny” from the court battle, that is not the case. Thomas agreed to settle out of court, having had enough of it all, just wanting to get on with her life and back to her art. The amount of the settlement has never been revealed, but according to Guy Mendes, a photographer and friend of Thomas, “she couldn’t tell us what the settlement was, but she said her children would go to college.”

“We didn’t want the conflict to go on forever,” said Thomas’ husband. “That’s not a good way to live.”

Ironically, it wasn’t the only time that Roberts would find himself in court battling over copyright. Roberts and Original Appalachian Artworks filed a copyright infringement lawsuit in 1986 against Topps Chewing Gum Inc., the Brooklyn company that had been selling the popular Garbage Pail Kids baseball trading cards. Roberts claimed the repulsive trading card parodies of the Cabbage Patch Kids were doing real damage to his angelic brand. As part of the out-of-court settlement, Topps agreed to modify the appearances of the Garbage Pail Kids to remove the resemblances.

Millions of happy kids, and millions of dollars

In 1988, Coleco (the company that was manufacturing the Cabbage Patch Kids dolls) filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and Roberts sold out for a little over $30 million. Hasbro took over the rights to produce the dolls from 1989 to 1994, with Mattel producing them from 1994 on. Today, full-size Cabbage Patch Kids dolls start as little as $29.99 in Canada.

Although Cabbage Patch dolls were still best-selling toys, the rage was clearly over. Still, by 1999, over 95 million Cabbage Patch Kid dolls had been sold worldwide.

Martha Thomas, who had touched so many lives, passed away in May 2013 at age 62 after battling ovarian cancer. At her funeral, many arrived with their handmade Doll Babies, which were all placed seated on a pew before her casket.

As for Roberts, he has stayed out of the spotlight for years; he still lives in his hometown and continues to head the privately held Original Appalachian Artworks. He spends much of his time gardening and caring for the grounds at BabyLand General Hospital, which is still open to shoppers looking to pick up a Cabbage Patch Kids doll or one of the shop’s original soft sculpture dolls that are still being hand-stitched there today. More than 130 million Cabbage Patch Kids dolls have been “born” since the early 1980s: one “birth” every 6.8 seconds. Millions of kids have known the joy that the dolls can bring, with cherished memories still being made today. And we have Xavier Roberts, a global supply chain, and Martha Thomas to thank for that.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.