I was barely 12 when I woke up on August 31, 1997 and my parents told me Princess Diana had died. I knew who she was, but barely. She’d been a figure on magazine covers, fodder for the tabloids my Mom told me not to thumb through in line at the grocery store, and had the same haircut as my Aunt who I thought was super cool and fashionable. But the news hit hard: a famous stranger had been killed tragically young in a terrible car crash, and even relaying the news to me seemed to make my parents emotional.

So I followed my parents’ lead. That afternoon, we went to my Uncle’s for his end-of-summer BBQ where I passed on the news to two kids I grew up with.

“Princess Diana died,” I announced solemnly while holding a badminton racket. I expected a mix of shock and sadness, and maybe confusion. I knew I was basically changing their lives.

“Ha! Di died — get it?” said one.

I rolled my eyes and sighed dramatically, proving that unlike them, I was grown up enough to actually get it.

“No,” I corrected, as if speaking to a small child. “She was very young and died in a car accident and it was awful. You can’t joke about it.”

The next weekend, my Mom and Dad got up at an ungodly hour to watch the funeral. I woke up near the end and found them both crying on the couch, so I started crying too and kept it up throughout the day. I thought about the card that read “Mummy” sitting on top of her casket, of her two sons walking so bravely behind her, and of all the people I saw bawling on TV. And, like the rest of the world, I became totally obsessed with her life and her death, asking my Mom to buy me commemorative books, listening to Elton John’s single on repeat, and buying the Princess Diana Beanie Baby. I gave my seventh grade speech on “The Life of Princess Diana”, picked up every magazine with Prince William on the cover, and tried to figure out if I should hate Camilla Parker-Bowles. Which was odd because Diana had been a stranger — a woman I’d never thought about until she died, and I was explicitly told to care about her. And now, 20 years later, I still do.

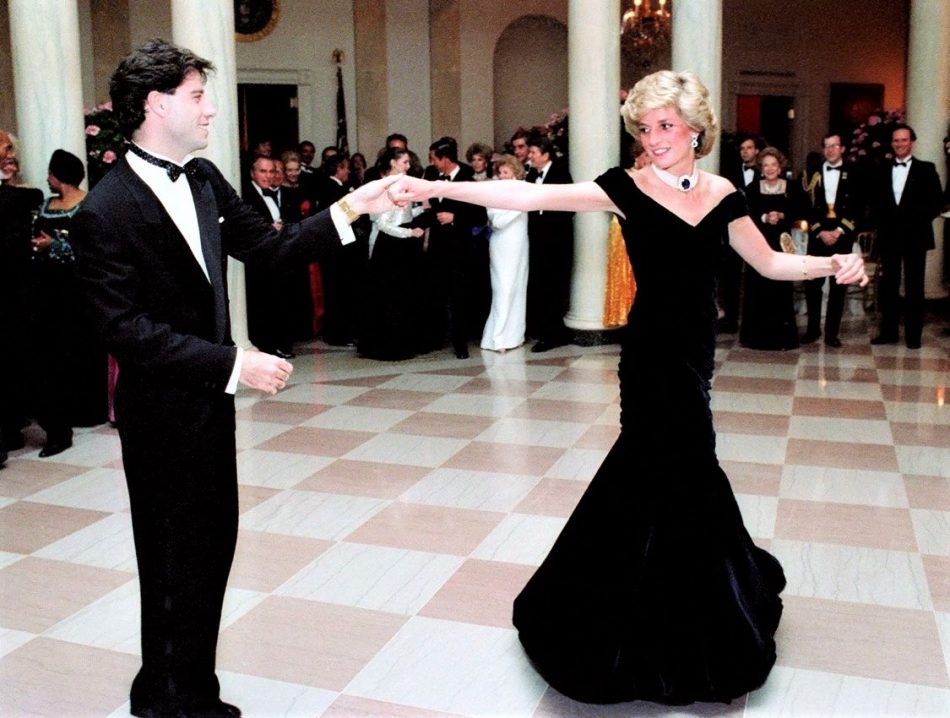

In retrospect, the death of Diana embodied almost everything I didn’t understand, but wanted to, because to me it represented adulthood: she had been glamorous, fashionable, popular. She had been married, raised two children, gotten divorced (something I thought was endlessly cool), and had spent a few days of her mid-thirties onboard a yacht with her boyfriend, who had heartbreakingly died too. She had been kind, generous, and campaigned for important causes like AIDS awareness and against landmines. She personified life, and then it was taken away. And at 12, nothing in the world seemed so unfair.

But of course, the older you get, the more you realize that death — tragic, expected, or a combination of the two — is constant. You realize that no one is guaranteed to live into old age, public figure or not, and that over time, you react to it with less performance because it gets a little more familiar. I cried more over the death of Princess Diana than I have family members I actually knew and very much loved, but it was her death that introduced me to the way we process it and who it’s claimed by, and what we turn loved ones into when they’re not here to live on their own terms anymore. Her death taught me about life. Particularly about how fucking unfair it is.

I’m now four years younger than Diana when she died in 1997. And, as an adult, I’ve reconciled that what I felt at 12 years old was the cocktail of feelings that come with celebrity death — especially if you’ve had no real prior experiences with death. But also as an adult, I understand the onus is on us not to villainize or to saint or to slant someone’s story to suit a narrative we feel more comfortable with. Princess Diana was the self and public-proclaimed Queen of Hearts, but she was also a grown-ass woman who came into her own in the midst of a shitty marriage that made her miserable. She embraced her reputation for being a free spirit and chose to live on her own terms and in her own way, and she applied that ethos whether she was aligning herself with charitable causes or hanging out on a boat with Dodi Al-Fayed. She was a person. And while I’ll never not want to cry when thinking about that heartbreaking card on her coffin, it’s sadder still to think that she was just like the rest of us: flawed, interesting, complex, complicated, and human. And not immune to the cruelness of mortality.