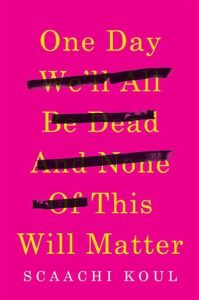

After growing up in a predominantly white neighbourhood in Calgary and receiving her fair share of obnoxious, hurtful, and straight-up horrifying insults, Scaachi Koul has a thing or two to say about racism, sexism, and navigating childhood as the daughter of Indian immigrants. As a senior writer at BuzzFeed, the 26-year-old journalist regularly writes about politics and popular culture. And in her powerful, honest, and at times laugh-out-loud-funny collection of personal essays One Day We’ll All Be Dead And None Of This Will Matter, she reflects on important and often difficult topics such as body image, Indian womanhood, rape and surveillance culture, fear of death, and parent-child relationships. Read on as we discuss her new book and she shares her thoughts on Twitter trolls, racism, and the awful year that was 2017.

So how would you describe your book in a nutshell? By the way, I loved it.

Oh good, I’m glad. I guess it’s a collection of essays about things that make me anxious and miserable.

What kind of response have you been getting from it?

It’s been good. I mean, if I want to dig for bad reviews, I can find it. But generally speaking, it’s been pretty positive. It’s heartening to hear brown girls read it and feel like it makes sense to them. You know, I’ve had a lot of white men read it too, which is kind of nice — they weren’t my target, but I appreciate that they picked it up and that it was something they could learn from.

Who was your target reader?

Brown women.

Have you always wanted to be a book author? Or was that kind of an unforeseen but natural evolution from your career as a journalist?

I mean, I think it’s like a pipe dream writers have in the back of their head. Like this is a thing I would do one day if someone would let me. I didn’t think anyone would let me. I don’t know. I wish I could go back to when I was 15 and appropriately inquire. I think I often don’t fully verbalize or articulate the things I would like to learn one day out of the anxiety of failing at it. So I usually don’t say anything and I just quietly chip away at it, and then when it happens I deal with that later. But yeah, I’m sure I did. I mean, everyone does. Even people that aren’t writers want to write books.

When did you decide you wanted to be a writer and go into journalism?

That was an easier choice, because I had no other skills. I wasn’t good at anything else. When I was in high school, I wrote for the school paper, I was an AP English student, and I had a 48 per cent in math. So your fate is written quite clearly when your options are that limited. So I needed to apply to a program that didn’t require a math grade but would allow me to write. So I applied to Ryerson and I got in. I just was never good at anything else. I had no other transferable skills. I wish I did — maybe I would have picked something else. But probably not. I’m also a narcissist so this is probably ideal.

You’ve talked a lot about how you’re trying to fill a gap in the culture — you didn’t grow up seeing yourself represented in popular culture or media. Do you think things have improved since you were a child?

Yeah, of course they have. But I wonder to what degree. People ask me that question all the time, but the only examples that they point to are Mindy Kaling and Aziz Ansari. So great, those are good shows, those are great actors, those are really cool creators. I’m so thankful that they’re around. But I don’t think we’re at a point yet where I’m able to take for granted creators that are brown and black. I don’t feel like I’m there yet. We’re still in a space of like, what kind of work do they get to do? Where do they get to sit? And do we constantly have to defend that? I’m even waiting for a bunch of dumb men to start smashing pots over their heads because Ocean’s 8 is women only. We’re still having those arguments. I don’t get comfortable very easily. But of course things are moving, but the pace at which they move is very slow, so I’m not giving anyone a pat on the back.

You’ve talked a lot about cyber bullying and harassment. What do you think is the solution to these problems?

I mean, it’s like a fundamental thing about how we raise our children. And how white families raise their white kids. And how people parent boys. And how we raise straight kids. It’s very elemental. And so it feels so condescending to be like, “raise your kids better,” but that’s a big part of it. It’s about the stuff that we consume. It’s about the things we read and the movies we watch and what we think is acceptable. I don’t think teenage boys or young men or old men come out of the womb thinking “I can be abusive to women.” I don’t think that’s inherent. I think you learn that somewhere. You either learn it — and talking to the men who have yelled at me recently, or ever, it’s like something about your dad. Your dad said something to you you thought was acceptable. Or you warped something about your mother. It’s really basic family stuff. And then the other element of it is: what did you see in a movie that you thought “well if we can laugh about this, then maybe I can do it.” There’s a historical element. I mean this goes back to like 200 years ago — so how much time do you have? But those are the biggest pieces to me when I look at these things.

So it comes down to education.

I have to think so. This is bred in. This isn’t something — I mean even the stuff that goes on with Twitter and how shitty the platform has been. The platform has been absolutely a fucking disaster. But deeper than that, the company and the men who run that company think it’s okay to ignore harassment as an issue. But why? Why do they think that? And deeper than that, there are a bunch of people who behave like that. And this is their truest self. Because they know they can’t do this at work but they can do this online, because there’s no punishment for it. Those are some of the things that I’m trying to tap into and I’m trying to make sense of it but I haven’t quite been able to grasp why.

I was reading about what happened when you put a call out on Twitter looking for non-white, non-male writers. It’s absolutely scary what happened to you. Has anything on that level happened since that?

No, because I think that I’m at a point now where my following on Twitter is large enough that if anyone said anything to me, there’s someone that would say something. Like the scale has tipped a bit in the last year. So not recently. There’s always something. Nothing that targeted. I think harassment, though it is something I still contend with, the scale has changed. I mean, I think it could still happen, I would just have to enter a new stratosphere with my career, which I just haven’t yet. I’ll let you know if it occurs.

So learning from this experience, do you have any advice for young women on how they can navigate the social media world?

There’s nothing I can say that is going to make it feel better if someone is threatening to kill you. So the only thing I can say, and I’ve said this so many times, is you just have to wait. And you don’t have to engage. You don’t need to stay. You don’t need to be on Twitter. You don’t need to play on the Internet. None of these are obligations. If you want it, if you want to stay, and if it happens, the only real thing you can do is just wait, because they will lose and they will go away and they will lose interest — that is the hope. It’s not a steadfast rule, and there are tons of women who have gotten it way worse than I have…. Generally speaking, I would say, it goes away. You just have to give it a minute.

In your interview with Elle, you were talking about how the media — which is largely white — doesn’t know how to talk about race with you. How do you think that white media and white people in general can better navigate these important conversations?

They can let brown and black people do it. That’s a pretty simple solution. They don’t have to take charge. It’s not necessary. And that’s not to say — and this is the other coin of that diversity hiring question. You should have those people be at the helm of those conversations but they don’t only need to be in those spaces. You can hire a brown person to be a business reporter. They can work in your tech section. They can work in your lifestyle section. But if you want to have an honest conversation about race, you need to look internally. So I get this question a lot from white journalists because they want me to give them an answer, and I can’t. You have to do stuff at your own organization.

What’s a piece of career advice that you’ve received that you could pass on?

I would say you shouldn’t listen to your own hesitation when you’re pitching ideas. Because a lot of the time when you’re a young writer you think: well, they’re not going to buy this. You have to ignore the voice inside of your head telling you it’s not going to work. And you just have to do it anyway. And I think it will yield better results than just waiting for your time to come up. Because it might just not come up. That number might not come up. And you just have to… That’s the best I have to say. The rest is luck.

Because a lot of your work is so personal, how do you find the courage to share such personal things about yourself?

I don’t think about that, because there is nothing in the book that I’m embarrassed or uncomfortable with. Like what, are you going to come to me at an event and be like “I hear you have knuckle hair.” Like okay, sure. It’s fine. I didn’t shave it for the first half of my life. It doesn’t make things more true or less true if you write them down. They don’t go away. Sometimes they don’t get better. It doesn’t change anything. The only time I’m cautious about it is when it involves other people, because then I’m telling stories that aren’t just my own. I’m cautious when I talk about my partner, when I talk about my parents. With stuff like me, like okay, what are you going to do? There is nothing you can do about it. And because I’ve already owned it, fine. I have yet to receive a repercussion from it more tangible than sometimes people come up to me and they probably feel a sense of intimacy with me that is one-sided. But that’s not really the worst thing in the world.

One of your notable articles was about how awful 2016 was. Now that 2017 is done, how are you feeling about it?

It was bad. It was all bad. Everything is bad. Was there anything good? No, it was a terrible year. It was confusing. It was a personally very rewarding and satisfying year. It was politically and contextually really awful. So I feel almost neutral because it kind of all balanced out. Like the world is ending and we’re definitely going to die and Trump is going to get us killed and I hate Justin Trudeau and everybody is racist and sexist and I have no faith in humanity. However, my book did really well this year [laughs]. So it’s hard to say. All years are bad. I don’t think I’ve ever ended a year and been like “that was a good one.” I’m really not sure I’ve ever done that. I’ve maybe said “okay, that was tolerable.” But I’m not an optimist. I look for the bad first.

What do you hope the book will leave readers with?

I hope it makes them feel a little less alone and I hope they get a laugh and I hope they hope it makes them call their parents more.

Portrait photography by Barbora Simkova.