Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion moments…

By Christopher Turner

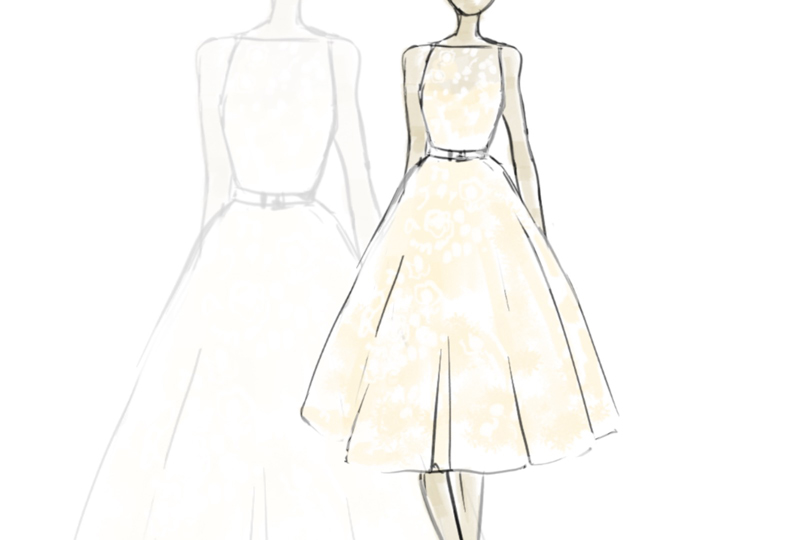

Illustration by Michael Hak

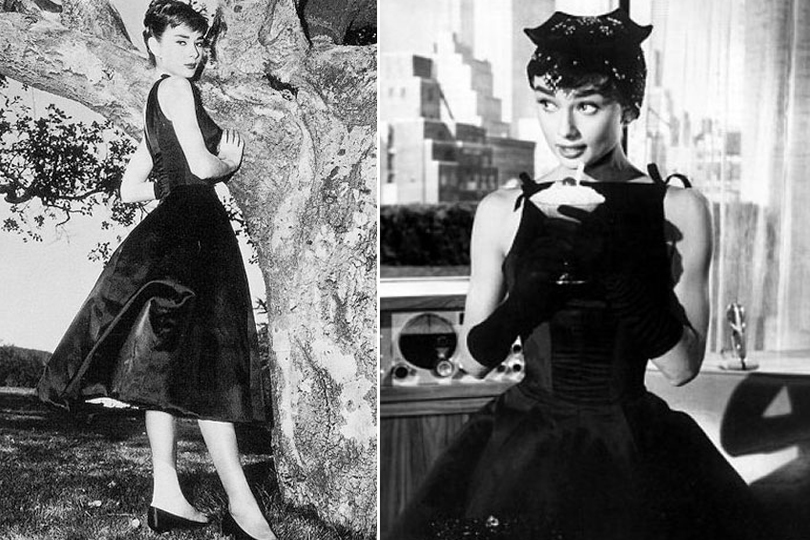

The iconic ivory lace tea-length gown that Audrey Hepburn wore to collect her Academy Award in 1954 for Best Actress for the 1953 film Roman Holiday is unanimously considered to be one of the best Oscar dresses of all time, consistently referenced on almost every historical best dressed roundup across the internet and in countless fashion tomes. The delicate sleeveless dress is incredibly lovely, but, surprise: the facts behind the dress’s design aren’t as clean-cut as the dress itself. The history of the dress is incredibly messy and the designer is often wrongly attributed, even by the most reputable of websites and books.

The actress’s Oscar-winning role saw her play a runaway princess who toured the Italian capital on a scooter with Gregory Peck. It was Hepburn’s first film role, propelling her to stardom, while the dress she wore to accept her Oscar was the beginning of her role as a Hollywood style icon: the beginning of a legacy of simple, timeless glamour.

Hepburn’s winning Oscar dress, which she referred to as her “lucky” dress, is often credited as being solely designed by French couturier Hubert de Givenchy, and it’s widely considered the first time the actress publicly appeared in a dress by the designer. However, this isn’t exactly true. It certainly looks like something Givenchy would have made at the time, but he did not design the original dress. Read on for more on who actually designed the dress, the controversial struggle between two of fashion history’s most famous designers, Hepburn’s lasting friendship with Givenchy, and how the lacy dress signalled a change for Oscar fashion to come.

Oscar night

The 26th annual Academy Awards were held on March 25, 1954, simultaneously at the RKO Pantages Theatre in Hollywood (hosted by Donald O’Connor) and the NBC Center Theatre in New York City (hosted by Fredric March). Young ingénue Hepburn was nominated for her role as Princess Ann in the 1953 romantic comedy film Roman Holiday, which was directed and produced by William Wyler. But according to her biographer, Barry Paris, Hepburn wasn’t an Oscar shoo-in—the coveted award was expected to go to Deborah Kerr that year for her performance in From Here to Eternity.

When a shocked and demure Hepburn stepped on stage to accept her first—and only—Academy Award, her lace dress captivated viewers. Her reluctance to look up while she spoke, and her exaggerated lashes fluttering on her cheeks, only emphasized the neckline of her dress and the beautiful lace fabric that swept across her collarbone. It was unlike any other dress worn on the Oscar stage before.

Of course, Hepburn wasn’t the only winner that night in this story. Roman Holiday would also land Head her own Oscar for costume design.

The Roman Holiday farewell dress

In 1952, Hepburn—then a young and unknown actress—was cast in the upcoming Paramount film Roman Holiday as Princess Ann. Head was the lead costume designer at Paramount at the time, and was assigned to design Hepburn’s entire wardrobe for the film. (Head would win seven Academy Awards during her 44 years working for Paramount, before she signed with Universal for the remainder of her career and winning her eighth and final Oscar there.)

Head designed all of the costumes Hepburn wore as Princess Ann—including a white lace midi dress with a shawl collar, wrap-over bodice and fitted waist, styled with a pearl choker and a Juliet style hat, that was worn in the closing scene of the movie. In that scene, Princess Ann held a press conference where she would see Joe (the reporter she had fallen in love with) for the very last time.

At that time, Head had been appointed the Academy’s official fashion consultant, and, according to Patty Fox’s 2000 book Star Style at the Academy Awards: A Century of Glamour, nominees would often nod to their characters with the gowns they wore to the Oscar ceremony. When the Oscars rolled around that year, Hepburn decided to wear the farewell dress to the ceremony, but removed the stately suited bodice that appeared in the final scene and added the Givenchy-influenced boatneck, keeping with trends of the time.

“It is definitely not by Givenchy,” says Kerry Taylor, who sold the dress through her eponymous British auction house in 2011. “It was a dress designed for the film by Edith Head which Audrey had remodelled for the Oscar ceremony—a ‘make do and mend’ mentality that she had inherited from those years of hardship during the war.”

After the awards, the ivory full-skirted look was given to Hepburn’s mother, Ella van Heemstra, who in turn gave it to a friend living in America. The dress remained stored away in a box at the bottom of a wardrobe until the family finally decided to sell it in 2011. On November 29, 2011, the dress was sold at auction to a private buyer for £84,000 by Kerry Taylor Auctions in London, United Kingdom.

“This beautiful lace dress is important because not only was it worn in the film Roman Holiday but was also worn to collect the Oscar itself,” said the auction house’s founder, Kerry Taylor. “It is the only time in the history of Oscar dresses that this ever happened to my knowledge. The demure white gown seems also sculpted to fit the willowy graceful figure of Audrey. The original dress was designed by Edith Head for the film, but for the Oscar night, Audrey altered the bodice—in essence, she Givenchy-fied it!”

The battle of the designers

Following Hepburn’s success in Roman Holiday, she was signed to a seven-picture contract with Paramount, and Sabrina—Billy Wilder’s Cinderella-inspired comedy—was set to be her follow-up film, with Humphrey Bogart and William Holden starring alongside her. The film was already in production during the lead-up to the 1954 Oscar night…and a conflict between Head and Givenchy was beginning to unfold behind the scenes on the film’s set.

By all accounts, the conflict between the two designers was instigated by Hepburn and started before Oscar night. Head was reportedly eager to tackle the costumes for Sabrina, writing in her memoir that was originally published in 1983 that she considered the film a “perfect setup” for her work. Different sources tell the story in slightly different ways, but essentially Hepburn convinced Wilder that she should go to Paris to select a few couture pieces that she would wear in the latter half of the upcoming film. Wilder had initially intended for Head to create all of the costumes for the film, but Hepburn rejected the designs and instead asked to wear “a real Parisian dress” for the part.

In the 2007 book Made for Each Other: Fashion and the Academy Awards, Bronwyn Cosgrave writes that Hepburn “went above Head,” arguing that it made sense that her titular character would return from Paris, where she is sent after a suicide attempt, with a wardrobe of couture that would be worn through the second half of the film. Wilder eventually agreed, but told Hepburn that Givenchy would not receive any credit and that she would have to pay for the clothes out of her own pocket. To Wilder’s surprise, Hepburn agreed.

Givenchy had just opened his tiny couture house in Paris after working at Schiaparelli, and was told that a Miss Hepburn would be coming into the store to take a look. Thinking that it was Katharine Hepburn whom he was going to meet, Givenchy was surprised when a tiny young woman wearing Capri pants, a T-shirt and ballet flats entered his shop.

“I told Audrey that I had very few workers and I needed all my hands to help me with my next collection, which I had to show very soon. But she insisted, ‘Please, please, there must be something I can try on,’” Givenchy reminisced in a 2014 interview with Vanity Fair.

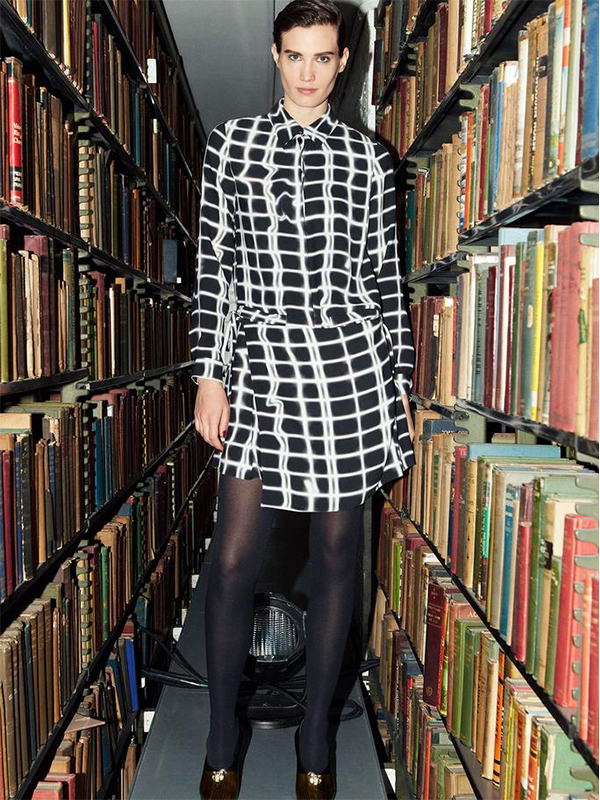

The Givenchy version of events found Hepburn selecting outfits for the film that had already been produced for the spring/summer 1953 collection, among them a black dress with a neckline that was used in Sabrinaand would inspire the neckline of the Oscar dress she would wear at the end of March. She liked it, per Vanity Fair, because of how it highlighted qualities on her body she thought were assets (her shoulders) and concealed what, in her opinion, was not (in the words of Givenchy himself, her “skinny collarbone”).

Both Head and Givenchy had misgivings about the way they were treated on Sabrina. In a 2010 Los Angeles Times piece excerpted from the memoir of Hollywood costume designer Jean-Pierre Dorléac (who was mentored by Head), Head maintained that she was responsible for all of the costumes in the film. Meanwhile, Givenchy was frustrated to find his name did not appear anywhere in Sabrina’s movie’s credits when the film hit theatres. Furthermore, when Sabrina was nominated for costume design the following year, it was Head who received the Oscar nomination, with Givenchy’s name nowhere to be found. Head maintained at the time that although Givenchy had designed Sabrina’s wardrobe in the second half of the film, all costumes were sewn and finished on the Paramount lot under her supervision. When she won the Oscar for Sabrina, she omitted Givenchy in her acceptance speech and the designer was furious. Perhaps in retaliation and in defence of the courtier she had grown so fond of, Hepburn had it written into her contract from then on that only Givenchy would be allowed to design her costumes and that he would receive full credit.

After Sabrina, Givenchy became a fixture in Hepburn’s increasingly successful career and he would exclusively create her wardrobe for both her private life and her seven subsequent films: Funny Face (1957),Love in the Afternoon (also 1957), Charade (1963), Paris When It Sizzles (1964), How to Steal a Million(1966), Two for the Road (1967) and, of course, Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It was a contract stipulation on which she insisted.

The actress and designer remained close friends, and collaborators, for the remainder of Hepburn’s life. She was even the face of the designer’s first perfume, L’Interdit, in 1957.

When she died on January 20, 1993, from a rare form of abdominal cancer, Givenchy was a pallbearer at her funeral—his final tribute to his dear friend.

Givenchy retired from fashion design in 1995, two years after the death of his friend. He died in his sleep on March 10, 2018, at the age of 91.

Legacy

In 2003’s The Complete Book of Oscar Fashion: 75 Years of Glamour on the Red Carpet, Reeve Chace writes that Hepburn “defined the new look of chic in her lacy tea-length gown of 1954.” And that she did. The changes that the star made to her Head-designed dress signalled a revolution in Oscar fashion. As movie stars’ images were no longer tightly controlled by studios, actresses made friendships and partnerships with the couture designers who dressed them. Hepburn and Givenchy’s relationship is one of the earliest examples of the evolution of the marriage of fashion and film.

It’s one of the reasons their names are constantly linked together to this day, and one of the reasons Head’s name is often forgotten when referencing Hepburn’s iconic ivory lacy tea-length Oscar dress. By enlisting Givenchy—even if it was at Head’s expense—Hepburn would ultimately embrace the identity as fashion icon that would leave a lasting mark on the red carpet.

In what could be seen as a case of tit-for-tat, the House of Givenchy has eliminated Head’s name from their history. When Emma Stone wore a dazzling gold Givenchy couture dress to pick up her Best Actress at the 2017 Academy Awards for her role in the musical La La Land, the brand said Stone was the first Best Actress winner to wear Givenchy since Hepburn. Sadly, no mention of Head’s contribution.

Still, the dress remains a key part of Hepburn’s legacy—but it’s also a key part of both Givenchy and Head’s legacy as well.

![]()

Want more? You can read THE STORY OF: The Iconic Black Givenchy Dress Worn By Audrey Hepburn In Breakfast At Tiffany’s and other stories from our The Story Of series right here.