Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

Elizabeth I was a long-ruling queen of England and Ireland, governing with relative stability and prosperity from November 17, 1558, until her death on March 24, 1603. Sometimes referred to as the “Virgin Queen,” Elizabeth was the last of the five monarchs of the House of Tudor, and is commonly recognized as one of the most successful and celebrated queens in history. In fact, the Elizabethan Era – the golden age in English history that has been widely romanticized in books, movies, plays and television – is actually named after her. Elizabeth herself remains one of the most recognizable monarchs of British royal history because of these depictions, and has become a fixture of modern-day pop culture thanks to her appearance and distinctive makeup. Her stark white-painted face and bold red wig remain part of her legacy, even centuries later.

Elizabeth’s iconic heavy white makeup wasn’t a standard beauty look of the time as many commonly believe: it was actually a form of camouflage, an attempt to cover up her bad skin, which had been left scarred after a near-death illness. But while her makeup (which was made with white lead and vinegar) did offer her a sort of mask, did it slowly poison her over time?

Read on for more on Queen Elizabeth I, her legacy, her incredible vanity, the role her makeup played in her brutally self-disciplined persona, and what role those thick layers of makeup may have played in her death.

England’s last Tudor monarch

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace in London, England, on September 7, 1533. She was the daughter of King Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn, who was famously beheaded when Elizabeth was just two years old. After Anne’s execution, her marriage to Henry was annulled, and Elizabeth, who had been born a princess, was declared illegitimate through political machinations. Despite this, Elizabeth eventually returned to the line of succession, and she eventually ascended to the throne on November 17, 1558, following the deaths of her brother Edward VI and then her older half-sister, Mary I, also known as Mary Tudor.

Elizabeth’s reign, which is often referred to as the Elizabethan Era or England’s Golden Age, was a time of peace and prosperity when the arts had a chance to blossom. Elizabeth understood the importance of art, theatre, music and literature, and how they were connected to the legacy of her country. With her support, English poetry, literature, theatre and art flourished, much of which is still read and watched today. For deeper context, Elizabeth’s reign supported the creation of works by such greats as William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe. “Elizabeth was passionate about theatre, and actively protected it from the Puritans who wanted it banned,” Alison Weir wrote in her 2013 biography The Life of Elizabeth I.

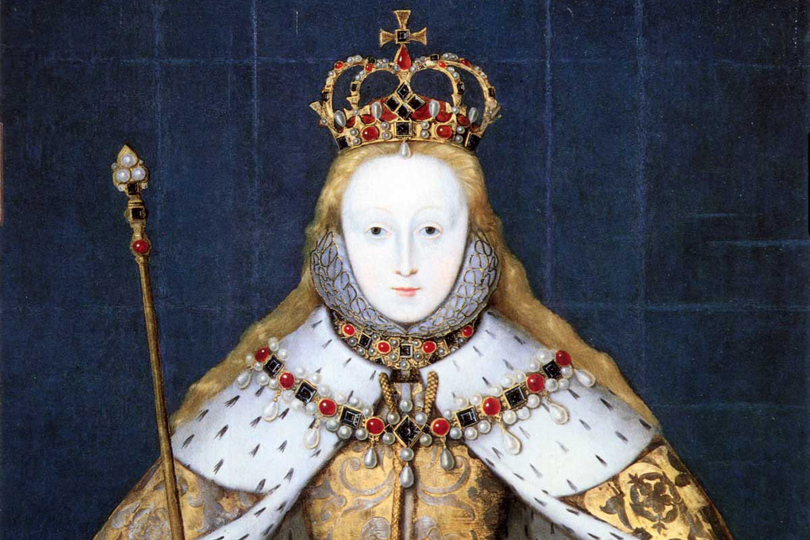

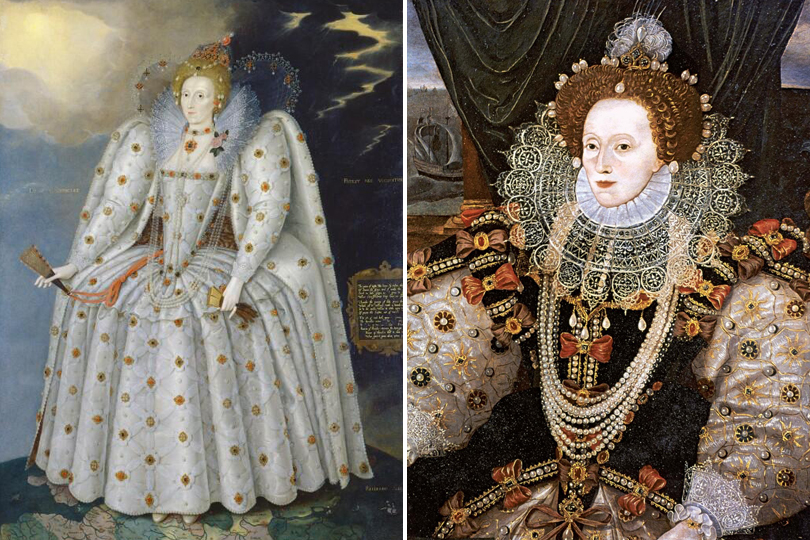

The Elizabethan Era was also a time when portraiture was the reigning form of painting, and artists, of course, honoured Elizabeth by painting her portrait. These images reveal that Elizabeth’s hair was naturally red (she didn’t start wearing wigs until later in life) and that she was an early fashionista in many ways: she loved jewellery and beautiful clothing. She was highly aware of the importance of her appearance in public, and went to great pains to achieve elaborate looks that she believed suited her the best.

Of course, it was also because she was famously vain. Elizabeth was known to order the destruction of any portraits of herself she didn’t like. This description of her comes from a journal written by André Hurault de Maisse (1539-1607): “When anyone speaks of her beauty she says she was never beautiful. Nevertheless, she speaks of her beauty as often as she can.”

Smallpox strikes

Four years into Queen Elizabeth I’s reign, on October 10, 1562, when she was just 29, she was struck down with a violent fever that left her bedridden and forced to remain in bed at Hampton Court Palace. It soon became clear that her illness was more than just a simple fever: she had smallpox, which caused the development of small blisters that would split before drying and forming scabs that left behind unsightly scars – if, that is, the patient survived the illness. At the time, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases due to its high illness and mortality rates; it was highly contagious and killed approximately 30 per cent of people infected, with no treatment and no cure.

Elizabeth refused to believe she could have contracted such a dreadful disease. Author Anna Whitelock wrote in her 2014 book The Queen’s Bed: An Intimate History Of Elizabeth’s Court that a notable German physician, Dr. Burcot, was invited to the queen’s sick bed; when he diagnosed her with smallpox, she sent him away, accusing him of being incompetent. However, as Elizabeth’s health declined further, Dr. Burcot was asked to make another visit and he again diagnosed the Queen with smallpox.

Elizabeth became so ill that she could barely speak. Seven days into her illness, it was feared the she was going to die, and her ministers hastily discussed a succession plan.

While the disease wreaked havoc on Europe, killing many monarchs, it did not kill Elizabeth. She ultimately survived, and the succession plan was put on hold. However, Elizabeth did not escape smallpox unharmed. She was left with permanent scars and marks on her face, which left the vain queen desperate to cover them up.

Smallpox not only altered her physical appearance but would leave her vulnerable to constant criticism and judgment – something she commented on in 1586 while addressing Parliament. Elizabeth said:

“We princes, I tell you, are set on stages in the sight and view of all the world duly observed; the eyes of many behold our actions, a spot is soon spied in our garments; a blemish noted quickly in our doings.”

Makeup as a shield

In her youth, Elizabeth didn’t really wear makeup, but after her battle with smallpox, she began using makeup to try and cover her scars, ultimately creating the iconic look that we know today.

During the Elizabethan Era, the English upper class considered pale skin incredibly beautiful, and a popular makeup available in the 16th century was called Venetian Ceruse (also known as ‘the spirits of Saturn’). This was a highly sought-after skin whitener made with vinegar and white lead sourced from Venice that gave women an incredibly pale look. Elizabeth began obsessively using this Venetian Ceruse in an attempt to cover her smallpox scars. The lead in the makeup, however, was poisonous, and over time, Venetian Ceruse caused hair loss and skin fading, two things Elizabeth suffered from as she got older.

Author Lisa Eldridge wrote in her 2015 book Face Paint: The Story Of Makeup that archaeologists have found traces of white lead in the graves of upper-class women who lived as far back as ancient Greece, and in China in the ancient Shang Dynasty (1600–1046 BCE).

But Venetian Ceruse wasn’t the only deadly makeup that Elizabeth used in her beauty routine. After her battle with smallpox, she also became known for her vibrant red lips. The bright red colour on her lips (and rouge on her cheeks) came from cinnabar, a toxic mineral containing mercury.

Today we know that mercury poisoning can cause memory loss, depression or, in extreme cases, death.

The biggest problem with Elizabeth’s use of Venetian Ceruse and cinnabar was how long she left them on – for weeks at a time with daily touch-ups, layering the poisonous makeup onto her skin over and over again, leaving plenty of time for the lead to soak into her skin. Then, when it eventually came time to remove the thick layers of makeup, Elizabeth used a mixture of eggshells, alum and even more mercury. This would only worsen the effects of the makeup that was slowly killing Elizabeth.

Unfortunately for her, when Elizabeth began losing her hair, she began wearing wigs that were dyed red…with even more mercury.

Elizabeth’s beauty was said to have faded badly with time. By applying makeup with mercury to her face on a daily basis, Elizabeth began to experience skin deterioration and hair loss, which she battled by applying even more makeup because she was so self-conscious about her image. According to historian John Morrill, Francis Bacon (a British philosopher and statesman) wrote at the time, “She imagined that the people, who are much influenced by externals, would be diverted by the glitter of her jewels, from noticing the decay of her personal attractions.”

End of a long reign

By the end of her life, Elizabeth was in a state of deep depression because of her deteriorating appearance, and she refused to have a mirror in any of her rooms. Along with her poor physical health, she showed signs of declining cognitive ability and delirium. Despite this, she refused to rest and reportedly stood for hours, which historians believe was because she was afraid that if she were to sit down, she would never get up again.

Elizabeth died on March 24, 1603, at Richmond Palace in Surrey at the age of 69, after a successful reign of 45 years. At the time of her death, she was reported to have a full inch of white makeup on her face. By this point, she had lost most of her teeth, suffered hair loss, and refused to be attended to and bathed. In G.J. Meyer’s 2010 book The Tudors: The Complete Story of England’s Most Notorious Dynasty, he describes her as “a pathetic spectacle, all the more so because throughout her reign she has been vain to the point of childishness.”

Elizabeth’s embalmed body was guarded in Whitehall Palace for three weeks before being laid to rest in a lavish funeral ceremony on April 28, 1603. Today her tomb can be found in Westminster Abbey in London, England, in the same vault as her half-sister, Mary I. The Latin inscription at the base of the tomb reads, “Partners in throne and grave, here we sleep Elizabeth and Mary, sisters in hope of the Resurrection.”

Because Elizabeth had no children, with her death came the end of the House of Tudor – a royal family that had ruled England since the late 1400s. The son of her cousin and former rival, Mary Queen of Scots, succeeded her on the throne as James I.

Legendary status

Elizabeth’s life story is one filled with drama and vanity and she has inspired countless artistic and cultural works throughout the centuries. She’s undoubtedly the most-often portrayed British monarch in films, portrayed on the screen by a wide range of actors including Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Judi Dench, Cate Blanchett, Helen Mirren and even Margot Robbie.

(Bottom L-R): Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth (1998), Helen Mirren in Elizabeth I (2005), Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007), Margot Robbie in Mary Queen of Scots (2018)

Scottish author and screenwriter George MacDonald Fraser once wrote: “No historic figure has been represented more honestly in the cinema, or better served by her players.”

She’s a character worthy of our fascination: a virgin queen who brought almost half a century of stability after the turmoil of her siblings’ short reigns. But one can’t deny that one of the biggest reasons we remain fascinated by her is because of her appearance: her flame-red hair, white face and lavish ensembles.

The exact cause of Elizabeth’s death remains a mystery because before her death, she refused to grant permission for a post-mortem to be conducted. However, today it is generally believed that she may have died of mercury blood poisoning, brought on especially by her decades-long use of the lead-based Venetian Ceruse, which was finally classified as a poison 31 years after her death.

Ultimately, it is impossible to say for certain what killed Elizabeth I. Regardless of whether or not her makeup killed her, what it has certainly done is helped ensure that she remains one of the most iconic and revered monarchs to have ever lived.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.