By Christopher Turner

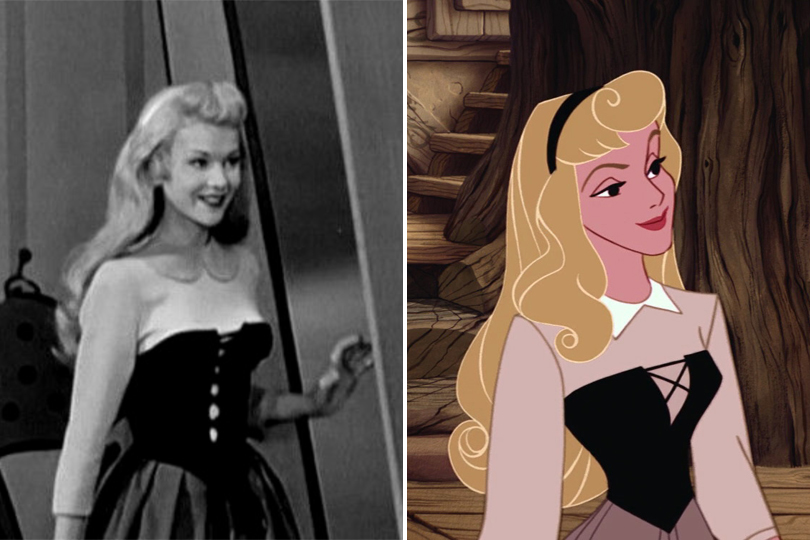

Despite contributing to three of the most enduring Disney films of all time, actress Helene Stanley never really became a household name. Still, she played a key role during Hollywood’s famed Golden Era and she was, in a way, a real-life Disney princess, serving as the inspiration and live-action model for Cinderella from Cinderella (1950), Aurora from Sleeping Beauty (1959) and Anita Radcliffe from 101 Dalmatians (1961).

Helene Stanley was born Dolores Diane Freymouth on July 17, 1929, in Gary, Indiana. She made her film debut in 1942 at the age of 14, starring as Sally in the low-budget movie Girls’ Town, and then worked steadily as a teenager, including as part of a teen dancing group called The Jivin’ Jacks and Jills, appearing in both Moonlight in Vermont (1943) and Patrick The Great (1945). In the mid-1940s, she started to work with MGM Studios and, as many actresses did in an effort to become more marketable, changed her stage name. As “Helene Stanley,” she signed with MGM, and immediately appeared in Thrill of a Romance (1945) and Holiday in Mexico (1946).

MGM producer Joseph Pasternak had intended on turning Stanley into a top actress, but when MGM’s executive team decided to change directions and focus their energies on actress Jane Powell, Stanley left MGM and went on to appear (mostly uncredited) in a string of films for a variety of studios. Her most notable appearance came a with a brief but memorable role in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle (1950). Despite her constant work, she never became a big star like some of her contemporaries.

Undeterred, Stanley pivoted to animated films when she was asked to be the “live model” for an upcoming Disney film. Beginning with Cinderella, Stanley acted out a live-action version of the story as a template for the final animated feature. That was just the start of her “double life,” where she would “star” in animated films while continuing to appear in small roles in live-action films.

Cinderella

Based on Charles Perrault’s 1697 fairy tale of the same title, Cinderella was the 12th Disney animated feature film to be released in theatres. By early 1948, Walt Disney had personally fast-tracked Cinderella to become the first full-length animated film since Bambi (1942). But, since Disney was still financially struggling following World War II and the Disney animators’ strike in 1941, it was decided to take a safe and tested approach to production of the film.

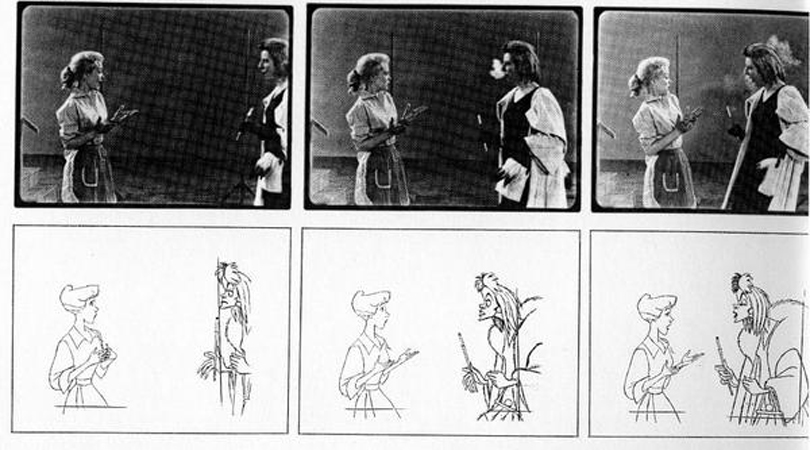

At the time, in order to get the most natural movements and subtleties captured on screen, Walt Disney had the actors, in full costume and makeup, act out the entire film on a sound stage, not to rotoscope (the process of creating animated sequences by tracing over live-action footage frame by frame), but for the animators to use as a reference.

“The financial condition of the studio was such that they couldn’t pour the lavishness into the production that they had with Fantasia or Pinocchio,” said film historian John Canemaker in the 2005 documentary From Rags To Riches: The Making of Cinderella. “So what they did was, they shot the entire film in live-action and they used this as a guide to do layouts for the film, for the cutting, for the way the action would flow into one another.”

When it came time to bring the title character to life…Walt Disney hired Stanley to perform the live-action reference for Cinderella. Acting alongside Stanley were Jeffrey Stone, the live-action reference for Prince Charming, as well as Mary Alice O’Connor (the Fairy Godmother), and Eleonor Audley (the Stepmother and Lady Tremaine). (Stanley also did live-action for one of the stepsisters, Anastasia, while Rhoda Williams modelled for Drizella.) Actress Ilene Woods, who was hired to be the voice of Cinderella, had previously been known for her eponymous radio show The Ilene Woods Show, which was broadcast at the time on ABC.

Starting in spring 1948, Stanley and the other actors were filmed on large soundstages mouthing to a soundtrack playback of the dialogue that had already been recorded for Cinderella. This wasn’t the first time that Disney had used live-action actors as a reference: live-action actors had also been used for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Pinocchio (1940) and Fantasia (1940).

The animators would work from the live performances when the actors were being filmed and then from giant blow-ups of each frame of the film. There was no tracing involved – everything was drawn freehand. Per Frank Thomas (one of Disney’s leading team of animators, known collectively as the Nine Old Men), the animators were not allowed to imagine anything that wasn’t present in the live-action footage, and to avoid difficult shots and angles. Thomas explained, “Any time you’d think of another way of staging the scene, they’d say: ‘We can’t get the camera up there!’ Well, you could get the animation camera up there! So you had to go with what worked well in live action.”

When Cinderella was released to theatres on February 15, 1950, it received critical acclaim and became a box office success, making it Disney’s biggest hit since Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and helping turn around the studio’s financial troubles. The film also received three nominations at the 23rd annual Academy Awards, including Best Scoring of a Musical Picture, Best Sound Recording, and Best Original Song (for “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo”).

The financial success of Cinderella allowed Disney to carry on producing films throughout the 1950s and begin building Disneyland, as well as developing the Florida Project, later known as Walt Disney World.

In the meantime, Stanley appeared on Broadway, was discovered by 20th Century Fox and was cast in a series of small roles in five different films, which were all coincidentally released in 1952.

Sleeping Beauty

A few years later, Stanley was part of a Walt Disney film once again. Disney had first considered making an animated adaptation of Charles Perrault’s fairy tale Sleeping Beauty back in 1938 with preliminary artwork submitted by Joe Grant, but it would be years before the project moved forward. Finally, after the tremendous success of Cinderella, Walt Disney officially announced in November 1950 that he was developing the story of Sleeping Beauty to become an animated feature film.

However, numerous delays and changes in direction meant that production didn’t actually start until July 1953, the same year that Stanley married small-time mobster Johnny Stompanato.

Mary Costa was cast as the voice of Princess Aurora, but when it came time to cast the live-action reference for the princess, Disney turned once again to Stanley. Ed Kemmer was cast as the live-action reference for Prince Phillip, while the live-action reference for Maleficent was provided by both her voice actress, Eleanor Audley, and dancer Jane Fowler, who also served as a model for Queen Leah. The Three Good Fairies were performed in reference footage by Spring Byington, Madge Blake and Frances Bavier.

As with Cinderella, Disney animators watched the actors act out the entire film and then worked off of giant blow-ups of each frame of the film. In this video clip below, two animators sketch Stanley in the scene where Aurora dances and sings the medley “Once Upon A Dream.”

It was a painstakingly tedious process, as everything was drawn freehand by the animators – there was no tracing involved.

Stanley spent over two years portraying Aurora for the Disney artists. After completing the live-action filming, she returned to the big screen in a number of small roles, and also made her television debut in 1954 in an episode of the long-running melodrama, Big Town, which was followed by a variety of appearances in other shows on the small screen. The following year, Stanley and Stompanato divorced in February 1955.

Back to Sleeping Beauty. The scheduled release of the film was repeatedly pushed back as the film sat in post-production. In the end, it took nearly a decade and $6 million to produce the film, which made it the most expensive Disney animated feature at that time. When it was finally released to theatres on January 29, 1959, Sleeping Beauty became Disney’s 16th animated feature film. While it was also nominated for Best Scoring of a Musical Picture at the 32nd Academy Awards, the initial release of the film was considered a box-office bomb, and that caused Walt Disney to lose interest in the animation medium. However, the film’s subsequent re-release in 1970 proved very successful, and it has since become one of the most artistically acclaimed Disney features ever produced. In 2019, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

101 Dalmatians

As the 1950s drew to a close, Disney was experiencing greater financial success than ever before thanks to Disneyland; however, feature animation – one of the company’s signature endeavours – had an uncertain future. After Sleeping Beauty disappointed at the box office, there was some talk of closing down the animation department at the Disney studio, but it was ultimately decided that production should continue on the next project, 101 Dalmatians.

Dodie Smith wrote the book The Hundred and One Dalmatians in 1956. When Walt Disney read it the following year, it immediately grabbed his attention: he recognized its widespread appeal, and promptly obtained the rights.

Stanley was called back once again and served as the inspiration and live-action model for the story’s frazzled mother, Anita Radcliffe. Meanwhile, Mary Wickes provided the live-action reference for Cruella de Vil.

As with the previous Disney films, actors provided live-action reference in order to determine what would work before the animation process begun. However, this time around, inexpensive animation techniques – such as using xerography during the process of inking and painting traditional animation cels – helped keep production costs down.

101 Dalmatians was released in theatres on January 25, 1961, and became the Disney’s 17th animated feature film to hit theatres. The film was a box office success, pulling the studio out of the financial slump caused by Sleeping Beauty, and became the eighth-highest-grossing film of the year in North America, proving that a Disney feature animation could still be a profitable endeavour.

In an interview with Pete Martin of The Saturday Evening Post, Walt Disney explained, “[Sleeping Beauty] was not the kind of picture to have the appeal that [101 Dalmatians] had. Because in [101 Dalmatians,] I had those cute personalities to hold it, you know, and it had more of a broad appeal. Sleeping Beauty was more of […a] spectacular fantasy.”

101 Dalmatians was Stanley’s final role in Hollywood. Following her work as a live-action model on the film, she formally retired from show business. She had married again two years before the film’s release, this time to Dr. David Niemetz, a physician from Beverly Hills; the couple had a son, David Niemetz Jr., in 1961, the same year 101 Dalmatians was released. Stanley died in Los Angeles on December 27, 1990, at the age of 61. The cause of her death was not reported.

While Stanley’s career in film and television was varied and vast, her name is largely unknown in Hollywood’s history – but she will always have a legacy thanks to her association with Walt Disney Studios. After all, without her grace and influence, three of Disney’s most beloved characters – Cinderella, Aurora and Anita – simply wouldn’t be the same. Another example of art imitating life.