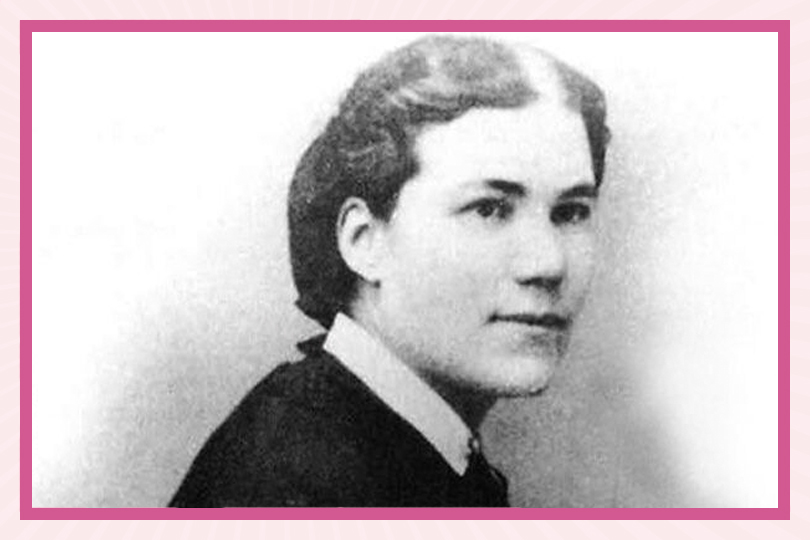

On May 25, 1861, Frank Thompson answered President Lincoln’s call for volunteers and proudly walked out onto the streets of Detroit as a newly minted Private and member of the Company F, Second Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment. In order to join the Union forces during the Civil War, you simply had to answer a few questions and prove that your handshake was strong. You didn’t need to undergo a physical examination beyond that. So, nobody noticed that Frank Thompson was actually Sarah Emma Edmonds, a 20-year-old woman from Canada.

Edmonds would go on to serve as an army nurse, and according to her memoirs, she went behind Confederate lines as a Union Army spy, all the while disguised as a man. Read on for a look at the life and legacy of this fascinating New Brunswick-born woman who played a part in the American Civil War.

The Early Years

Edmonds was born December 1841 in New Brunswick, the youngest of six children. As the fifth girl in the family, she was yet another disappointment to her father, and he made sure she knew it.

Growing up on a farm, she gained a skill set that would become important in her later life: riding, shooting, hunting, and nursing. She was at home on a horse, wielding a gun, from a young age.

When she was 15 years old, her father attempted to force her into marriage with an older man. Perhaps inspired by the stories she read as a young girl about teenage Fanny Campbell, who disguised herself as a man and got involved in all sorts of adventures with pirates, Edmonds ran away, cut off her hair, and hid behind men’s clothing. She assumed the identity of “Frank Thompson.” Passing as a man, she found a job as a Bible salesperson, first travelling New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, then eventually landing south in Michigan.

The Civil War

Edmonds was still living in Michigan when the Civil War began in 1861. According to her biography in the Canadian Encyclopedia, she faced a dilemma: as a Christian pacifist, she was against war, but she was also anti-slavery and wanted to help the Union forces. As a compromise, she decided to volunteer as a nurse.

She headed to Detroit to enlist and, passing the army’s very basic requirements and cursory examination, she successfully became Private Frank Thompson, Company F, Second Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Comfortable on a horse and armed with a weapon, she fit right in with the best of the men. According to an article in Canada’s History, Edmonds was soon “initiated into the realities of war” and “withstood the trauma of howling artillery shells slicing bloody lanes through compact masses of men, tossing body parts, viscera, and broken weapons and equipment high in the air.”

Interestingly, Edmonds wasn’t alone in the ruse. There were reportedly 250 women that joined the Confederate side and 400 in the Union army, all disguised as men. Beyond that, women participated as nurses, cooks, laundresses, and camp followers.

Behind Enemy Lines

Edmonds began as a (male) nurse but soon her participation extended into more controversial and dangerous territory: behind Confederate lines as a spy for the Union Army.

First, in 1862, nearly a year into her time in the forces, Edmonds was appointed as a regimental mail carrier. She delivered mail by horseback between army camps. But then, the Union Army started looking for new volunteers to act as spies. According to Edmonds’ memoir, Nurse and Spy in the Union Army: Comprising the Adventures and Experiences of a Woman in Hospitals, Camps and Battlefields (published later to great acclaim in 1865), she was recommended.

Edmonds passed the interview at the US Secret Service headquarters in Washington, DC, and according to her memoir, she used silver nitrate to darken her skin, donned a wig and shabby clothes, and, pretending to be a slave, made it into the Confederate stronghold at Yorktown, Virginia.

She recounts how she gathered useful information for the Union Army, at times disguised as a slave, a female Irish peddler, and as a Confederate soldier. Edmonds was a master of disguise and was able to maintain her secret identity until 1863 when she contracted malaria. She needed to get medical help right away, but did not want to blow her cover by exposing herself to a doctor.

Instead, she travelled north to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, changed into a dress, and was admitted to the hospital as Emma Edmonds. By the time she was cured and tried to return to her post, she discovered an army bulletin posted in the window of a newspaper office: Frank Thompson was wanted as a deserter. Once found, he would be punished for his desertion by death.

Edmonds knew her military career was at an end but she was not done with the war effort. She travelled to Washington and secured a position as a nurse (this time, as Sarah Edmonds) for the United States Christian Sanitary Commission. She remained there for the rest of the war.

Later Years and Legacy

After the war, Edmonds published her memoir and donated all the royalty earnings to the war relief fund. She went back home to Canada and in 1867, married a fellow New Brunswicker named Linus Seelye, becoming Emma Seelye. They raised three sons together and eventually settled on a farm in Texas.

She managed to apply for an honourable discharge for “Frank Thompson” and secured herself a veteran’s pension. She was also the only woman to ever be accepted fully as a member of the Union army’s veterans organization, the Grand Army of the Republic.

Unfortunately, she spent her last years suffering from illness and financial struggle. On September 5, 1898, she died from a stroke.

But her legacy lived on. In 1901, her remains were moved to the Civil War veterans’ plot in the Washington Cemetery—the only female buried there. The details and extent of her involvement in espionage as recorded in her autobiography have since been contested, and her memoirs are now considered a liberal blend of fact and fiction. However, some of the experiences she recounted do apparently stand up to contemporary records and regardless of the exact nature of her involvement, her story remains a fascinating example of women in wartime.

In 1988, she was inducted into the United States Military Intelligence Hall of Fame and the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame, and in 1990, the New Brunswick Hall of Fame.