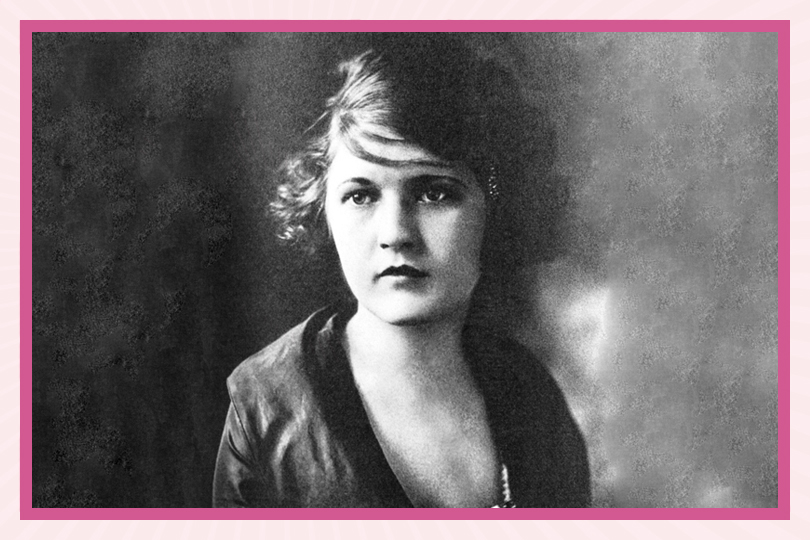

When we try to conjure up an image of the quintessential flapper of the Jazz Age, nobody fits the bill more than Zelda Fitzgerald, the legendary socialite and iconic wife of the American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald. She was celebrated in her time for her beauty, her charm, and her infectious love of a good time, and was Fitzgerald’s longest lasting muse—and perhaps, some people have even suggested, his unacknowledged literary collaborator. Here, in an effort to understand the woman behind the pop culture cult figure, we take a look at her early life, her marriage, her own artistic activity, and the tragic turn her life took.

Early life

Zelda Sayre was born on July 24, 1900, in Montgomery, Alabama, to an old Southern family with a history of slave-owning and support of the Confederacy. Her mother, Minnie Machen Sayre was artistically inclined, and her father, Anthony Dickinson Sayre, was a powerful judge. They provided her with a financially and socially privileged upbringing, and Zelda was noted to be a “free-spirited” and “undisciplined” child. According to F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work, her parents named her after “a gypsy heroine in a novel.”

Even as a young girl, she was known for her fun-loving ways and her beauty. In May 1918, she graduated from Sidney Lanier High School and was voted “Prettiest” and “Most Attractive” in her class on her way out. According to Professor Kirk Curnutt, a specialist of the Fitzgeralds, she spent her youth “starring in ballet recitals and basking in the glow of elite country club dances.”

Two months after her high school graduation, she met the man who could change the course of her life: F. Scott Fitzgerald, a charming 21-year-old army officer stationed nearby that harboured literary ambitions. Their relationship quickly took off, however she also entertained other suitors, since she held doubts that he would be able to provide for her financially. But when Fitzgerald’s manuscript of This Side of Paradise was accepted for publication and he got his first magazine short stories printed, she gave their relationship a chance. On April 3, 1920, they tied the knot at New York City’s St Patrick’s Cathedral.

Icon of the flapper age

Fitzgerald’s novel was an instant success, and they were swept up in a wave of fame and fortune. They became symbols of the “free-wheeling lifestyle and relaxed morals of what became known as the Lost Generation,” and Zelda herself became a celebrity and her opinions on modern love and other topics were gobbled up by the media. They lived an extravagant life of over-spending, over-indulging, and over-drinking.

In 1921, Zelda became a mother when she gave birth to their first and only child, a daughter who they named Frances “Scottie” Fitzgerald. They lived between America and Europe, joining the artistic expatriate circle that included other creative celebrities of the age like Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway.

Zelda became a fixture in the social scene of Jazz Age-era New York and Paris, and was not only a muse to society at large, but also to her husband. Fitzgerald’s female characters—for example Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby—were largely inspired by Zelda. According to Curnutt, “both her vivacity and tragedy live on in the many characters she inspired in her husband’s novels and short stories.”

Marital, artistic, and mental health struggles

Their marriage became rocky in 1924, when Zelda took an interest in a French naval aviator while they were spending their summer in the French Riviera. Then, in 1927, Fitzgerald began a flirtation with a young actress. According to his own admission, his attraction to her was due to her constructive use of her artistic talents.

One view is that this “implied criticism made Zelda determined to accomplish something for herself.” First, she threw herself into dancing, revisiting her childhood practice of ballet. She took lessons and studied under a celebrated ballerina in Paris, but at 28 years old, the window for a serious career in the field had already passed. She also turned to writing, at first as an attempt to earn money for her ballet lessons. Several magazines published her short fiction.

According to F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z, Zelda’s mental health crumbled under the pressures of the ballet industry. She writes that “friends had previously noticed some nervous habits and the erratic turns her conversations would take, but by 1930 her behavior was obsessive and out of control.” She was hospitalized in Paris, then in Switzerland, and was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

By 1932, she was admitted to Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore. During her six-week stay, as part of her program of recovery, she was encouraged to express herself through writing. In a marathon sprint, she penned her novel Save Me the Waltz, which she had published that year. Unfortunately, it was not well-received and her career as a writer never took off. Fitzgerald himself “deeply resented the book” and not only blamed the financial burden of her hospitalization for his inability to complete his next work but he also accused her of stealing its plotline for her novel.

As noted in the preface for this 2013 collection of her writings states, “the attributions of Zelda Fitzgerald’s publications are muddied because editors put F. Scott Fitzgerald’s byline on her work—either as collaborator or as sole author.” This was largely because his name sold magazines. He also polished and edited her work, so this further complicates things. But Zelda resented that her works were deemed “unsellable without her husband’s name.”

While the fact that her life and persona inspired many of his literary characters is obvious and uncontested, the degree to which she may have influence—or even contributed—to his work has been hotly debated ever since. According to F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z, while Fitzgerald “did use bits of her diary and letters…and later incorporated material from her letters,” she was “not his collaborator…his work was his own.”

The Collected Writings, which aims to make her original works more widely available so that her skill as a writer can stand on its own, suggests that the speculation about the “possibility of Zelda Fitzgerald’s unacknowledged participation in F. Scott Fizgerald’s work” is not supported by evidence and is just guesswork.

In her own lifetime, Zelda hinted that a passage from Fitzgerald’s book The Beautiful and Damned was “lifted straight from her missing diary.” There were other possible instances of his appropriation of her writing or experiences into his work, and his publishing fame always overshadowed any of her own literary ambitions. A recent television drama on Amazon Prime starring Christina Ricci that fictionalized the life of Zelda took this idea and ran with it, depicting Zelda as an unfairly overlooked literary genius.

Later life and legacy

After her career as a ballerina staled and her career as a writer failed to take off, she turned her efforts towards art. Her cityscapes, depictions of dancers, flowers, and religious subjects showed considerable skill, but she did not find critical acclaim in this either; Time magazine referred condescendingly of her art show in New York as her “latest bid for fame.”

The cycle of temporary recovery and relapse continued, and she spent the rest of her life in and out of hospitals. As their surviving letters illustrate, the Fitzgerald’s remained deeply in love, but their marriage was suffered under the strain of his alcoholism, her mental health issues, their careers, their mutual infidelity, and their unhealthy lifestyles. He famously wrote in a letter that “Perhaps fifty percent of our friends and relatives would tell you in all honest conviction that my drinking drove Zelda insane—the other half would assure you that her insanity drove me to drink. Neither judgment would mean anything.”

Fitzgerald himself “descended into alcoholism and literary obscurity,” moved to Hollywood in an attempt to rescue his career, and died of a heart attack at the end of 1940. Earlier that year, Zelda had moved back home to Montgomery to live quietly with her mother, though they never divorced. Meanwhile, Curnutt notes, their daughter Scottie was largely raised by nannies and then enrolled in boarding school.

In 1948, while checked into Highland Hospital, a fire broke out. Trapped in her locked room, Zelda died at the age of 47 years old.

The time of her death coincided with a renewed interest in Fitzgerald’s work. As his work became popular again, according to Curnutt, critics and biographers “tended to depict Zelda as equal parts liability and inspiration.” Likewise, Ernest Hemingway’s popular book A Moveable Feast, published in 1964, contributed to her reputation as a “harridan who derailed her husband’s career.”

But in 1970, Nancy Milford released a biography of Zelda that rehabilitated her reputation and instead positioned her as “a symbol of thwarted artistry,” and she became a feminist icon. In 1992, Zelda was inducted to the Alabama Women’s Hall of Fame as an author, ballerina, and painter. Her novel has been given new attention and is now taught in English classes, her artworks have been exhibited around the United States, and her life story continues to fascinate and inspire movies, documentaries, and novels.