By Sienna Vittoria Asselin

There’s no denying that Queen Charlotte ruled the screen in the first two seasons of Bridgerton, even though she was merely a supporting character. And now with her own dedicated spin-off prequel, depicting her early years at court, she has truly become a household name in pop culture. But who was the real Queen Charlotte, and was her marriage with George III truly a love story? Was she really a Black Queen of Britain that bridged racial divides? And what about all the snuff and the Pomeranians? Here, we look back at the life and legacy of the historical woman that inspired Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story.

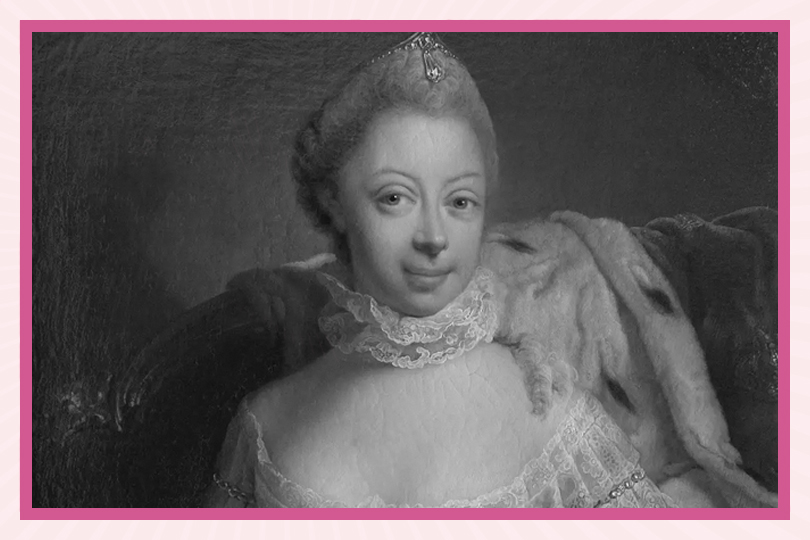

Early Life of a German Princess

According to her biographer, royal historian Catherine Curzon, the future Queen Charlotte was “not born to greatness.” Nobody would have thought that this unassuming princess from a “little corner of Europe” would end up ruling beside the King of Great Britain.

She was born on May 19, 1744, the youngest daughter of Duke Charles Louis Frederick of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Princess Elizabeth Albertina of Saxe-Hildburghausen, the rulers of a small northern German duchy in what was then the Holy Roman Empire. Princess Charlotte grew up at Untere Schloss (aka Lower Castle) in the district of Mirow.

Curzon notes that Princess Charlotte received a “mediocre” education. She learned how to manage a household but was kept out of politics. Curzon writes in The Real Queen Charlotte that what made her so remarkable was how unremarkable she was at first; she was not political, not ambitious, and only aspired to a happy home. She was described as plain, but perfectly pleasant and “sweet-tempered.” Those are not the qualities of the bold and beautiful queens that typically make history, but they are what made her the perfect wife for the timid and unassuming new king who also valued hearth and home.

Queen Consort: A Royal Love Story

In 1760, the young King George III succeeded to the throne and began looking for a wife. He chose Charlotte’s name from a list of eligible Protestant ladies, thinking that they would be a good fit; he was 22 years old, and Charlotte was 17 years old. He announced his intention to his council in 1761, setting in motion the process to arrange the match, and sent a group of escorts to Germany to fetch her. She arrived dutifully in London on September 8th. Six hours later, they were married. They did not have a chance to get to know each other whatsoever, and as with any arranged royal marriage, their chances of marital happiness were slim.

But, just as depicted in the romantic television drama, their marriage appears to have been a true love story from the start. They settled into an easy domestic routine right away. When George warned Charlotte that she must “never meddle in politics” she was happy to oblige. Less than a year later, the new Queen Charlotte gave birth to her first child, a little Prince of Wales. Over the next 22 years, George and Charlotte became the parents of 15 children, including nine sons and six daughters. All but two survived to adulthood, which is a remarkable thing in a time of such high infant and child mortality. Queen Charlotte oversaw their education and was very involved in her children’s lives. She also built strong and devoted friendships with her ladies in waiting and cultivated a happy home of domesticity for her husband and children.

While she happily stayed out of politics, her interests ranged widely. She presided over a glittering, fashionable court, and according to Curzon, she was a stickler for etiquette and social protocol. The first known debutante ball was hosted in her honour and the tradition lasted until Queen Elizabeth II canceled the balls in the 1950s. She was passionate about gardening and oversaw beautiful royal gardens. She was also an amateur botanist, which was considered a fashionable “ladylike” science at the time and was an important patroness of the botanical garden at Kew, an important scientific institution at the time. She founded orphanages, patronized a hospital, and was a musical connoisseur.

And true to Bridgerton‘s depiction, she did indeed love her snuff, a finely-ground smokeless tobacco inhaled through the nose. According to Curzon, she earned the nickname “Snuffy Charlotte,” and she had an entire room at Windsor Castle dedicated to her collection of the luxury product. And she did in fact love her Pomeranians. She had her own beloved pet Pomeranians and gifted them to other members of the royal family.

One of the fascinating aspects of her story and legacy is the debate around her heritage. Bridgerton depicts Charlotte as a Black woman, and some historians believe that she may have been England’s first Black royal, possibly of distant African descent. And since so many of the royal families across Europe can trace their lineage back to her, via her granddaughter Queen Victoria, this calls into question the racial identity of European royalty at large.

The theory was popularized nearly 25 years ago, when genealogist Mario De Valdes y Cocom traced Charlotte’s ancestry way back in time to a Black branch of the Portuguese royal family. However, many historians now reject the theory and say that his evidence was thin and the connection too distant.

And even if it was true, the real Regency England was nowhere near as diverse as the show portrays; their marriage certainly did not bring about any sort of racial equality. Unfortunately, Bridgerton‘s Lady Danbury’s observation that “we were two separate societies divided by color until a king fell in love with one of us” is one of fiction. Slavery was still present in the British colonies and people of colour in Britain worked in positions of domestic service, either as paid or enslaved servants.

A Love Story Turned Tragedy: The Later Years

Everything changed once King George III’s health began to deteriorate. According to Curzon, in 1788, George experienced his first “bout of mental illness.” He suffered physical pain and mental distress, including periods in which he talked until he foamed at the mouth. It happened again in 1801. Curzon writes that he became “sleepless and often violent” and that “he made lurid accusations of adultery against Charlotte,” who in turn began to suffer when she stopped eating and started having trouble sleeping. She began to tear out her prematurely graying hair and descended into a deep depression. Charlotte had lost her husband and best friend. The optimistic start to their marriage was transformed by his ill health, and she was transformed along with it. Her gentle demeanor gave way to a fierce temper, which she often directed at her daughters.

George III did receive treatment, which helped temporarily, but things were never the same again. The King was officially “declared insane” in 1811 and unfit to rule; Parliament turned authority over to their son, the Prince of Wales and future George IV, who ruled as regent for his father, giving the “Regency period” its name. Unfortunately, during the parliamentary debate over who would hold power during George’s illness, Queen Charlotte resisted handing over the reins to her “dissolute” son, and this caused estrangement.

Meanwhile, Queen Catherine was given official custody of her husband and she stayed loyally by his side until the end. George III’s heartfelt words give a glimpse into their relationship: “The Queen is my physician, and no man can have a better; she is my friend, and no man can have a better.” Once she became “more keeper than companion,” Curzon writes in The Real Queen Charlotte, she “mourned for the man she had known and loved.”

At the age of 74, Queen Catherine died on November 17, 1818, after nearly 60 years of marriage. Due to George III’s mental state, he did not understand that his wife was dead, and straw was scattered across the courtyard to muffle the sounds of the horses during her funeral procession. Fifteen months later, King George III died, and the royal lovers were, writes Curzon, reunited “in eternal rest.”