By Sienna Vittoria Asselin

The First Nations peoples of Western Canada experienced tumultuous political change and upheaval in the late nineteenth century–their way of life was challenged, and their rights either stripped away or hotly debated. At the centre of this negotiation was one fascinating woman known to us as Jane Constance Cook. As a translator, mother, advocate, and leader, she made an impact on her family, her community, and on our country’s history at large. Read on for a look at the life and legacy of Jane Constance Cook, an important figure in our country’s history that is–as is so often the case with women, and especially Indigenous women–largely forgotten.

The Early Years

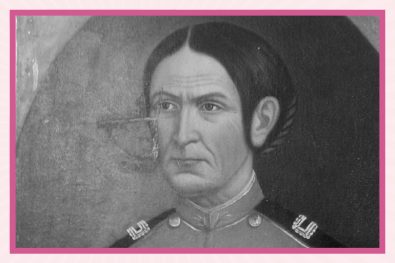

She was born in 1870 as Ga’axsta’las, or Jane Constance Gilbert in English, to a family of mixed heritage. Her mother was an Indigenous noblewoman from the village of Tsaxis (Fort Rupert, Vancouver Island, BC) and her father was an English trader and sea pilot. Some sources say she was born on Vancouver Island and others say that she was born at Port Blakely on Puget Sound, Washington, and later brought to Tsaxis.

After some travelling, Ga’axsta’las was entrusted to a missionary couple who raised and educated her in Tsaxis, her mother’s village. She therefore grew up bilingual and comfortable in both worlds, amongst both cultures. This cultural fluidity would give her an edge in her later work, as we will see.

We don’t know a lot about her childhood, as she only appears in written sources as of 1881 in the census at Tsaxis. But we can place her story in the context of the time and place to understand her early years and later work.

According to her biography, Standing Up with Ga’axsta’las, written by Professor Leslie A. Robertson and the Kwagu’Ł Gixsam Clan, she lived through “a period of intense upheaval for First Nation peoples.” A year after she was born, the Indigenous people were declared wards of the state in the new province of British Columbia. And when she was six years old, the government introduced the Indian Act, which “deprived aboriginal societies of the right to govern themselves, generated classifications that defined membership, racialized mobility and social behaviour, and sought to assimilate indigenous peoples.”

The upheaval that this caused had a lasting impact on Ga’axsta’las, and when she was older, she would go on to become a highly skilled and influential advocate for her people.

Motherhood and Being a Mother to Her Community

In 1888, she married a man named Nage (or Stephen Cook). He was also educated by missionaries. His mother was Indigenous and his father European.

They raised their family in ‘Yalis (on Vancouver Island). Together, Nage and Ga’axsta’las ran a general store and a salmon saltery. Later, they joined forces with their sons and built a successful fishing fleet. They also took on leadership roles in the Native Brotherhood of British Columbia, a First Nations rights organization.

They went on to raise 16 children together, constantly opening their home to those needing shelter, including people recovering from loss, travellers, or the sick. They fed anyone in need from her well-tended orchards and her kitchen, and as a traditional healer and midwife, Ga’axsta’las became a cherished member of her society.

Furthermore, Ga’axsta’las lived as a devoted Christian for her whole life. She was the president of the Anglican Women’s Auxiliary for more than 30 years and ran weekly meetings in the village, discipling women and supporting them through difficult situations.

But unfortunately, Nage and Ga’axsta’las faced tragedy after tragedy. They lost several children to illness and disease, as well as to the First World War.

First Nations Leader and Advocate

Throughout her years as a wife and mother, Ga’axsta’las’ was involved in advocating for First Nations peoples in British Columbia.

Her deep understanding of both cultures and legal systems allowed her to become a fierce champion for her people. According to Canada’s History, as the “grip of colonialism tightened around West Coast nations, Cook lobbied for First Nations to retain rights of access to land and resources.”

Her advocacy was a long-term effort and took many forms, as her biography outlines in great detail.

For example, being bilingual in English and Kwakwala, Ga’axsta’las was able to be a bridge between cultures. She translated sermons, speeches, and legal and extra-legal testimonies between English and Kwakwala. She served as an official court interpreter for trials and hearings from the 1910s onwards.

There are also several specific, historic highlights from her career that deserve highlighting. For one, Ga’axsta’las testified at the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission of 1914, an important government inquiry into “Indian” land claims and reserves. She also translated the words of the Kwakwaka‘wakw chiefs that made land claims.

She was also the only woman on the executive of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia in 1922. This was an early political organization composed of chiefs and other aboriginal leaders, and her voice was an important one. She spoke on behalf of commercial and food fishing rights and for nonracist health services.

In the 1940s, she stood with the Native Brotherhood in its fight for Indigenous peoples to benefit from the rights of Canadian citizenship without losing Indian status and hereditary privileges.

Later Years and Legacy

Ga’axsta’las died in 1951 in her early 80s after a long life at the centre of her family, her community, and her people. Her legacy lives on, as many of her descendants are still dynamic figures in First Nations structures of health, community and cultural development, education, law, resource rights, and local government. According to her biography, they all trace their passion for politics to Ga’axsta’las and her legacy of public engagement.

Robertson writes that her “legacy is apparent in her descendants’ ongoing participation in the political struggles of First Nation peoples in Canada.” She is remembered as a “woman of strength who demonstrated the importance of family relationships,” and she played an important, though often overlooked, role in the history of our country.