Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

It’s summertime, the sun is beaming, and you suddenly realized it’s time to really slather on the sunscreen. The reason? Sunlight contains ultraviolet (UV) radiation; the types we need to worry about are UVA and UVB rays. These rays affect your skin in different ways: UVA rays can cause redness, irritation and cellular damage, while UVB rays equate to burned skin. We know you know that sunscreen is designed to protect your skin from these damaging rays, but read on to find out more about the history of the product…and about our relationship with tanning and sun protection over the years and around the world.

BTW Sunscreen is the most important step in a good skincare routine – seriously! So if you’re not already wearing sunscreen each and every day, this is your reminder to start.

The first sunscreens

Sun protection, in a variety of forms and with varying success, has been around since early civilizations. For example, ancient Egyptians used extracts of rice, jasmine and lupine plants to help protect their skin from the sun’s blistering heat, while ancient Greeks used olive oil. Among the nomadic sea-going Sama-Bajau people of the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia, a common type of sun protection was a paste called borak or burak, which was made from water weeds, rice and spices; in Myanmar, thanaka, a yellow-white cosmetic paste made of ground bark, was traditionally used for sun protection. Zinc oxide paste has also been popular for skin protection for thousands of years.

Our love-hate relationship with the sun picked up steam in the 20th century. In North America and in Western Europe before the 1920s, tanned skin was associated with the lower classes, because they worked outdoors and were exposed to the sunlight. As much as they could, people went to great lengths to protect against sunlight exposure, with full-length sleeves, and women sporting sunbonnets and other large hats, headscarves and parasols shielding the head.

Fashionably speaking, one of the original forms of sun protection came in the 1910s in the form of sun-protective clothing and modest bathing costumes that included skirts, bloomers and black stockings.

The concept of tanning was only made chic years later, when Gabrielle Coco Chanel caught too much sun on a Mediterranean cruise in 1923. The photographs of her disembarking in Cannes set a new precedent of beauty, a look that symbolized health and wealth, and people began purposefully sunbathing to resemble her look and get that glow. Her friend Prince Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucigne later said: “I think she may have invented sunbathing. At that time, she invented everything.”

There are records of early synthetic sunscreens and sunburn creams being tested in the late 1920s, including experiments from H.A. Milton Blake, a young South Australian chemist. After years of experimenting and with funding from friends and family, Blake produced 500 tubes of his “sunburn cream” through the newly created Hamilton Laboratories in 1932. Blake’s cream was the first-known commercially available sunscreen in the world, and Hamilton sunscreen still exists to this day.

The first major commercial sunscreen product was developed by French chemist Eugene Schueller, the founder of L’Oréal, and brought to market in 1936.

Two years later, an Austrian chemist named Franz Greiter set out to invent his own effective sun protection cream. As a mountain climber and skier, Greiter frequently suffered from sunburn, one of the worst occurring when he climbed Piz Buin, the highest mountain of the Silvretta area at the Swiss-Austrian border. In 1946, Greiter introduced what may have been the first effective “modern” sunscreen, called Gletscher Crème (Glacier Cream), although it has been estimated that the original Gletscher Crème only had an SPF of 2. Regardless, the product subsequently became the basis for the brand Piz Buin (named in honour of the mountain where he allegedly received the sunburn that inspired his concoction), which still sells sunscreen products today.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Green, a US airman and pharmacist, created a greasy gelatinous substance called “red vet pet” (red veterinary petrolatum) to protect himself and other soldiers from the hazards of sun overexposure in the Pacific tropics at the height of World War II. Heavy and unpleasant, it worked primarily as a physical barrier between the skin and the sun. After the war, Green decided to mix the red vet pet concoction with cocoa butter and coconut oil to create a less heavy and less greasy sun protection product. That product would eventually become Coppertone suntan cream.

Sunbathing had caught on across the globe by this point, with magazines encouraging it, while sunlight therapy became a popularly subscribed cure for almost every ailment from simple fatigue to tuberculosis.

At the same time, swimsuits’ skin coverage began decreasing, with the bikini radically changing swimsuit style after it made its appearance in 1946. In the 1950s, many people began using baby oil as a method to increase tanning.

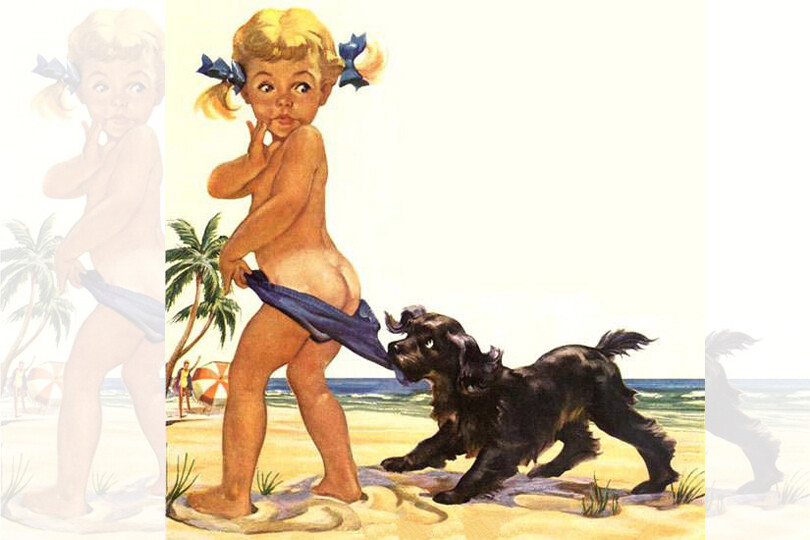

It’s important to note that the purpose of most sun protection products at this point was not to block out the UV rays of the sun, but to enhance or darken a tan. Ads for Coppertone helped reinforce the idea that a sun protection product was to “safely” acquire a tan. The brand became famous in 1953 when it introduced the Coppertone girl, drawn by an illustrator named Joyce Ballantyne who used her three-year-old daughter, Cheri, as the model. The popular advertisement showed a young blonde girl in pigtails staring in surprise as a Cocker Spaniel puppy sneaks up behind her and pulls down her blue swimsuit bottom, revealing her bottom to have a lighter tone than the rest of her body; the tagline reads “Don’t be a pale face, use Coppertone.” Sales boomed as the glamour of sunbathing continued into the 1960s.

Standardized rating

Coppertone led the way, but other chemical sunscreens and lotions were also hitting the shelves. Despite the emerging warnings about a potential link between sun exposure and skin cancer, the love of a suntan endured.

With that in mind and with sunscreen products becoming widely used, it was important to standardize the strength and effectiveness of each product, which is why Greiter introduced the concept of the SPF rating in 1962.

SPF stands for Sun Protection Factor, and the number beside it indicates how well the sunscreen protects the skin against sunburn. For example: Say it takes 300 seconds for skin to burn with sunscreen, and 10 seconds to burn without it – 300 divided by 10 is 30, so the SPF is 30. You can determine the effectiveness of a sunscreen by multiplying the SPF factor by the length of time it takes you to suffer a burn without sunscreen. For example: If you develop a sunburn in 10 minutes when not wearing a sunscreen product, in the same intensity of sunlight you will avoid a sunburn for 150 minutes if you’re wearing a sunscreen with an SPF of 15.

People loved their tans

Once the 1970s rolled around, SPF – which had started at 2 – advanced all the way to a level of 15. However, most people weren’t sure what that meant, and some assumed it meant they could stay in the sun longer without any need to reapply. And still, even though more studies were being done that showed a link between sun exposure and cancer, people loved their tans. In fact, in 1971 Mattel introduced Malibu Barbie, a doll with tanned skin, sunglasses, and her very own bottle of suntanning lotion.

For years, Greiter’s SPF rating was the only innovation in sunscreens and suntan creams, while development efforts were focused on making sunscreen protection longer lasting and broader spectrum, as well as more appealing to use. In the 1970s, Piz Buin introduced a line of sunscreens with ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B filters (i.e., broad-spectrum sunscreen). Another advancement in protection came in 1977, when water-resistant sunscreen was introduced into the market.

The following year, the US Food and Drug Administration finally adopted Greiter’s SPF calculation and proposed the regulation of sunscreens, recommending standards for safety and effectiveness. These guidelines – some parts of which never took full effect – mostly dealt with SPF testing and labelling. However, the official document did state, “In the long run, suntanning is not good for the skin.”

That sun safety message was starting to sink in, although the glamour of sunbathing and tanning continued. In the 1970s, methods of sunless tanning – such as Coppertone self-tan – grew in popularity, and by 1978, the tanning bed was reintroduced as a quick (and popular) way of bronzing the skin.

And now the innovations started coming fast and furious. In the 1980s, zinc oxide hit the market in a variety of colourful shades, gaining popularity after lifeguards began smearing the thick, zinc oxide paste on their noses and on their cheekbones to protect against sunburn. Low-SPF sunscreens were slowly replaced by those with higher sun protection factors. The 1990s brought the advent of spray-on and gel-based sunscreens.

People also tried another innovation to maintain their suntanned skin while avoiding the dangers of the sun’s rays. Tanning beds, which by now had been around for years, hit their height of popularity in the 2000s, becoming a $5 billion a year habit with tanning beds in most gyms and tanning salons seemingly on every city corner. But research was showing strong connections between indoor tanning and melanoma, and by the 2010s, regulations were introduced in North American and Europe placing restrictions on tanning salons and banning people under 18 from using tanning beds. However, there were no regulations on how often an adult could use a tanning bed. Nonetheless, the allure of artificially bronzed skin (both from tanning beds and directly from the sun) finally began to dwindle as more and more studies were published on the relationship between sun exposure and skin cancer.

Today

Exposure to the sun is vital to your overall health and well-being. Soaking up those rays can ward off depression, strengthen your bones, and even help regulate your blood pressure. Yet, as we all know, too much bare-skin exposure to the sun can cause early skin aging, and increase the risk of skin cancer by 90 per cent. So it’s clear: good sunscreen is vital to good health.

We tend to think that sunscreen is only necessary in the height of summer, when you can almost feel the UV rays soaking into your body. But those harmful ultraviolet rays are abundant no matter what season it is or what the weather is like. Even on an overcast day, up to 80 per cent of the sun’s rays are being absorbed by your skin. And in the winter months, the presence of snow can nearly double the amount of ultraviolet radiation that bombards your skin. This means, every single day of the year, no matter what the weather is like, if you are going to be outside for even 10 minutes – or less, for individuals with paler skin – you need to apply an SPF product to maintain healthy skin. The easiest way to do this is outside of those summer months is with an SPF-packed moisturizer (since wearing a dense, pore-clogging sunscreen all day is a little excessive). We’re still making advances in sun care, but many daytime moisturizers and lip balms have an SPF built in that is lightweight, broad-spectrum, fast absorbing and even skin soothing.

Which one is best for you? Well, it all boils down to personal preference…just make sure you’re wearing it.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.