Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

In the early hours of September 15, 1954, Marilyn Monroe stood on a subway grate in New York City wearing a little white cocktail dress, flirtatiously trying to keep it down against an upward breeze. It was all part of a scene for the whimsical comedy The Seven Year Itch, directed by Billy Wilder, which would be released the following year. While the moment only lasted a couple of seconds on the big screen, the scene would go on to become one of the most iconic moments in movie history, and the images of Monroe wearing the simple white dress would become the most popular element of her legacy, turning it into one of the most famous dresses in history. Ironically, costume designer William Travilla, who created the dress, didn’t think much of it, once referring to it as “that silly little dress.”

The filming of the scene was chaotic at best and Travilla’s white cocktail dress has a pretty complicated history, including rumours that he didn’t actually design it. And, despite the roar of approval from fans, the dress sadly played a role in Monroe’s divorce from baseball legend Joe DiMaggio.

Here’s the full story of the white ivory halter dress that Monroe wore in that famous scene from The Seven Year Itch, and the consequences that rippled far beyond the few seconds of wind that blew the dress upwards.

The little white dress

William “Billy” Travilla, professionally known as Travilla (pronounced Tra-via) was an American costume designer who had a close working relationship with Monroe, as well as a brief affair. Their first on-screen collaboration came when Travilla created the costumes for Roy Ward Baker’s Don’t Bother to Knock (1952), which was followed by Travilla creating Monroe’s costumes for her next seven films, including the iconic floor-length pink silk column dress that Monroe wore in the pivotal music sequence in the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), directed by Howard Hawks. The actress adored his clingy, figure-hugging designs: “Billy Dear, please dress me forever. I love you,” she once wrote to him.

The Seven Year Itch was the seventh film that Travilla had worked on with Monroe during their time at 20th Century Fox. He sketched the design of the film’s soon-to-be-famous dress while on vacation with his wife, Dona Drake, and then began crafting it upon his return.

The ivory-white cocktail dress is bias-cut and made from rayon-acetate crepe, a fabric heavy enough to swing as Monroe walked, but light enough to catch that all-important breeze. The halter-like bodice has a plunging neckline and is made of two pieces of the softly pleated fabric that come together behind the neck, leaving the wearer’s arms, shoulders and back bare. There is a zipper at the back of the bodice and tiny buttons at the back of the halter. The halter is attached to a band situated immediately under the breasts, and the dress fits closely from there to the natural waistline. A narrow belt wraps around the torso, criss-crossing in front and then tying into a small neat bow at the waist, at the front on the left side. Below the waistband and the little belt is a softly pleated skirt that falls around the mid-calf. Travilla described it as “cool and clean, in a dirty, dirty city.”

Of course, there were the rumours that Travilla hadn’t actually designed the dress. According to the book Hollywood Costume: Glamour! Glitter! Romance! by Dale McConathy and Diana Vreeland, he had just bought it off the rack. Travilla, of course, valiantly denied this.

Coming to life on the big screen

The Seven Year Itch is Billy Wilder’s 1955 film adaptation of George Axelrod’s 1952 three-act play about a middle-aged husband – left alone for the summer while his wife and son vacation in Maine – and the girl in the apartment upstairs. Marilyn Monroe played the girl upstairs (in the film, the character’s name is actually credited as The Girl), and Tom Ewell, reprising his role from the play, played Richard Sherman, the middle-aged husband. A summer of flirtation between the two neighbours leads to the film’s climactic scene when, after the pair catch a movie on 52nd Street, Monroe’s character pauses over a subway grate as a blast of air from a passing train ensures her dress takes flight. “Feel the breeze from the subway! Isn’t it delicious?” she says flirtatiously.

The film was a major commercial success, although Wilder would later call the film “a nothing picture” and claim he wished he had never made it under the moral restrictions of the time, which prohibited a story about adultery from showing any adultery.

The Seven Year Itch was filmed between September and November 1954, with Monroe’s iconic subway grate scene filmed towards the beginning of production. An hour after midnight on September 15, 1954, Monroe stood atop a subway grate at the corner of New York’s Lexington Avenue and 52nd Street ready to shoot the scene, while a member of the crew crouched under the grille beneath her heels operating a wind machine. A few feet away behind a police barricade, about a hundred photographers and between 2,000 and 5,000 spectators (who all reacted loudly whenever her skirt blew up) looked on trying to catch a glimpse of the star. “The Russians could have invaded Manhattan and nobody would have taken any notice,” Monroe’s publicist Roy Craft later recalled.

Then-20th Century Fox’s East Coast correspondent Bill Kobrin told the Palm Springs Desert Sun that it was Wilder’s idea to turn the late-night shoot into a media circus. Monroe knew to expect a crowd of onlookers, so that night she was careful to make sure she wasn’t showing too much once the fan underneath her started blowing. While she always caught the dress before it blew up over her head, she still took precautions to make sure anyone watching on the street didn’t see too much: she wore two pairs of white underwear, so that once the fan blew the dress upwards, nobody got a glimpse of anything they shouldn’t have.

Despite 14 takes that night, the crew still couldn’t get it right, due in part to the constant camera flashes and incessant noise created by the thousands of fans on the street. A few weeks later, the scene was reshot on the 20th Century Fox lot in California, though the original location shots taken that night in New York were used for advertisements and promotions for the film when it was released.

The scene’s role in Monroe’s divorce from Joe DiMaggio

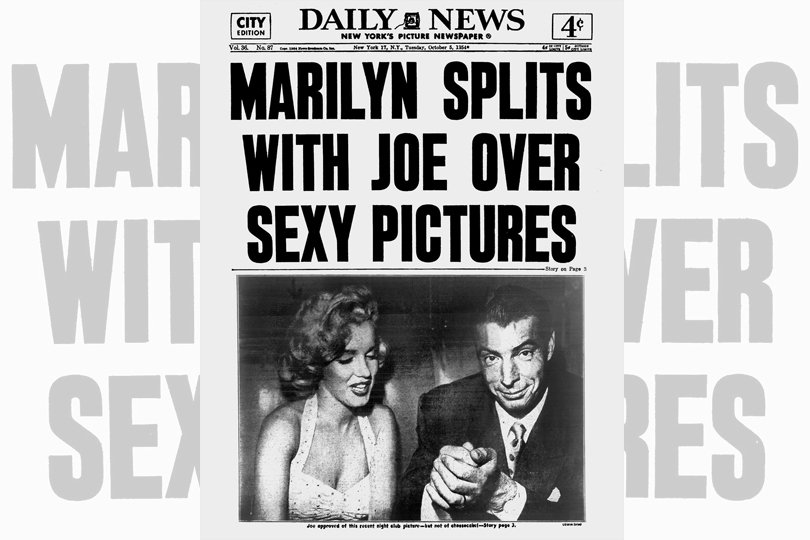

Despite the roar of approval from fans, Monroe’s husband at the time, New York Yankees centre fielder Joe DiMaggio, dubbed the greatest all-around baseball player of his era, was less than pleased with what he felt was an “exhibitionist” scene.

Monroe and DiMaggio had been married in January of that same year, and the union was troubled from the very start, mostly due to DiMaggio’s jealousy and controlling attitude; he was also physically abusive. The night of the skirt-blowing scene in front of Manhattan’s Trans-Lux 52nd Street Theater was the final straw. Photographer George S. Zimbel recalled everything going deathly quiet as Monroe’s disapproving husband stormed across the set and very publicly left the scene. Then a violent fight between the couple occurred immediately after filming stopped, first in the theatre lobby and later in Suite 1105 at the St. Regis Hotel, where Monroe and DiMaggio were staying. After returning to California in October 1954, Monroe filed for divorce from the baseball player after only nine months of marriage, on grounds of “mental cruelty.”

On October 5, 1954, New York’s Daily News ran the front page headline: “Marilyn Splits With Joe Over Sexy Pictures.”

Though the two shared only a brief marriage, they were able to repair their tumultuous relationship a few years later. At the beginning of 1961, Monroe and DiMaggio rekindled a friendship while she was hospitalized for depression at a psychiatric clinic in New York. Despite remarriage rumours that popped up in the press, the two maintained a good relationship as friends for the remainder of Monroe’s life.

On August 5, 1962, Monroe died from an overdose of barbiturates at her Los Angeles home, and officials ruled her death a probable suicide. She was 36. A heartbroken DiMaggio, with the help of Monroe’s half-sister Berniece Baker Miracle and business manager Inez Melson, arranged the funeral service at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery on August 8. For 20 years afterwards, DiMaggio had a half-dozen red roses delivered to her crypt at Pierce Brothers Westwood Village Memorial Park and Mortuary in Los Angeles three times a week. There were rumours that DiMaggio was preparing to propose again before Monroe’s death, but those rumours have never been confirmed. After her death, DiMaggio refused to discuss Monroe publicly and never married again.

Back to the dress

Publicity photos from The Seven Year Itch’s pre-dawn shoot and the film’s iconic scene live on to this day, and have turned Travilla’s flirty white halter dress into arguably one of the most recognizable costumes in film history. It has been imitated countless times in film and television, and is a staple for nearly every Marilyn Monroe impersonator around the world…not to mention the predictable Monroe Halloween costumes that can be spotted every single year. There’s even a 26-foot-tall travelling statue wearing the dress titled “Forever Marilyn.”

As for the original dress, after Monroe’s death in 1962, Travilla kept the dress locked up with many of the costumes he had made for her throughout their time working together, to the point the collection was rumoured lost.

Following Travilla’s death in 1990, a costume sketch for the dress sold at auction for $50,000. As for the actual dress, actress Debbie Reynolds purchased it for $200 to be part of her private, very robust movie costume and prop collection. (Reynolds had hoped to eventually open a museum of her own Hollywood memorabilia.) However, in June of 2011, Reynolds was forced to sell off assets to avoid bankruptcy, and those assets included her entire collection of Old Hollywood memorabilia, among which was Monroe’s dress. During an interview with Oprah Winfrey to promote the sale in 2011, Reynolds said of the famous white dress: “It’s turned an ecru colour because it’s very, very old as you know by now.”

The dress sold at auction for a reported US$4.6 million, the most money ever paid for a movie costume. The winning bid was made over the phone, and the dress is now part of a private collection – the mysterious owner has remained unidentified.

The last time the pleated ivory white dress was seen in public was in October 2012, for the “Hollywood Costume” exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. It was a last-minute addition to the exhibit, made possible by another actress, Meryl Streep. The exhibition’s curator happened to tell Streep that she was hoping to add Eliza Doolittle’s Ascot dress from My Fair Lady to the show. Streep said she knew the dress’s current owner, and helped the curator track her down. It turned out the woman didn’t have the Ascot number, but she did, in fact, own Monroe’s iconic costume. The anonymous owner agreed to lend the dress to the exhibit. However, it hasn’t been seen since, although more than a few replicas have made very public appearances.

So much for it being just a “silly little dress.”

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.