Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion moments…

By Christopher Turner

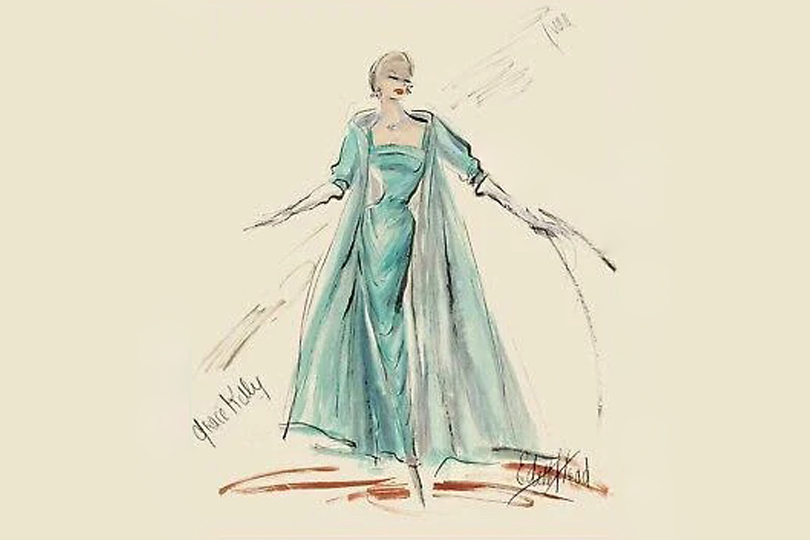

Illustration by Michael Hak

It’s one of the most memorable Oscar gowns of all time, renowned for creating the template for what we now call “timeless” on the Academy Awards red carpet: the icy blue satin gown that Grace Kelly wore to the 27th annual Academy Awards on March 30, 1955, where she won Best Actress for her role in The Country Girl. The gown is unanimously considered to be one of the best Oscar dresses of all time, consistently referenced on almost every historical best-dressed roundup across the internet and in countless fashion tomes. But, unlike so many of the most influential “fashion” moments in Hollywood history, the dress didn’t come from a renowned fashion house. It came from a studio costume department—designed by one of cinema’s great image-makers, Edith Head.

The dress is also burned into our collective consciousness because Kelly’s big Oscar night wasn’t the first time, or the only time, she wore the satin confection. She wore it in public two other times, at the film’s premiere the year before the Oscars and on the cover of Life magazine weeks after the ceremony.

Kelly wasn’t known for repeating her glamorous looks, but this dress had the perfect balance of glamour and restraint that made the repeat appearances a sensible choice for the quintessential 1950s Hollywood blonde. It also offered a level of elegance that went beyond the era’s everyday red-carpet standard.

Here’s the story of the gown that changed Oscar fashion and served as the inspiration for countless dresses that came after—and the story of Edith Head, the woman widely considered to be the most important figure in the history of Hollywood costume design.

How Edith Head found her way to Hollywood

Edith Head was born Edith Claire Posener on October 28, 1897, in San Bernardino, California, to Anna E. Levy and Max Posener. Her parents divorced, and in 1901 her mother married Frank Spare; the newlyweds opted to pass the young child off as their biological child, switching her surname. She grew up in various towns and camps in Arizona, Nevada and Mexico, before attending the University of California (where she earned her B.A.) and Stanford (where she earned her M.A.). Shortly after she completed her studies and began her career as a schoolteacher teaching French and art at the Hollywood School for Girls, she married a salesman named Charles Head on July 25, 1923.

Because of her husband’s drinking problem and her reduced teaching salary during the summer months, Head began looking for work to help supplement their household income. She spotted a classified ad in the Los Angeles Times that the Famous Players–Lasky studios (which was later absorbed by Paramount Pictures) was looking for a sketch artist to create costumes for the upcoming Cecil B. DeMille silent film, The Golden Bed.

Head was taking evening classes at Chouinard Art College, but lacked any significant or professional art, design or costume experience. Undaunted, she wrote the studio asking for an interview, got one and was then hired on the spot for $40 a week—more than double what she made teaching. The on-the-spot hiring was thanks to her diverse portfolio. Howard Greer, head of the studio wardrobe department, later described the interview with Head in Designing Male, his memoirs that were published in 1951.

“…A young girl with a face like a pussy cat crossed with a Fujita drawing appeared with a carpetbag full of sketches. There were architectural drawings, plans for interior decoration, magazine illustrations and fashion design. Struck dumb with admiration for anyone possessed of such diverse talent, I hired the gal on the spot.”

Years after Head had secured the job, she admitted to “borrowing” other students’ sketches from Chouinard Art College for her job interview with the studio: “I was studying seascape and all I could draw was oceans. I needed a portfolio, so I borrowed sketches—I didn’t steal them, I asked everybody in the class for a few costume design sketches. And I had the most fantastic assortment you’ve ever seen in your life. When you get a class of 40 to give you sketches, you get a nice selection.”

Instead of firing her for her lack of skill—which became apparent on Day 1—Greer taught her to sketch. As he had suspected, Head had a natural talent for costume design, and within six months she was not only sketching in Greer’s style but developing a style of her own. She worked her way up from sketcher to costume designer by way of apprentice assignments, and within two years she had begun designing costumes for the studio’s silent films, starting with Raoul Walsh’s 1925 silent film The Wanderer. By the 1930s, she had established herself as one of Hollywood’s leading costume designers, and in 1938 Head was named chief designer at Paramount, in charge of a costume department with a staff of hundreds…the first woman to head a design department at a major studio.

Although Paramount maintained that their actresses were not allowed any say in what they wore in the films they appeared in, Head would regularly talk with the actresses to find out what they liked to wear, and what they thought they looked good wearing. She became known as “The Dress Doctor,” and built a loyal following of actresses, including Barbara Stanwyck, Elizabeth Taylor and Grace Kelly, who insisted on working with her.

In 1953, the first year the Academy Awards were televised, Head was named the Oscars’ first fashion consultant, and was charged with making sure the stars dressed modestly enough to avoid running afoul of the censors. “I was appointed guardian of hemlines and bodices,” she said of the Oscar position she held until 1981.

Thanks to her role with the Academy Awards and her relationships with Hollywood’s biggest actresses at Paramount and later at Universal Studios, Head became America’s best-known and most successful Hollywood designer, and a bit of a celebrity herself.

Head boasted that she was a magician: she took ordinary women and, through the magic of fashion, transformed them into screen sirens.

“Accentuate the positive and camouflage the rest,” Head liked to say.

Her approach and her relationships clearly worked. Head was nominated for an unprecedented 34 Academy Awards, winning a record eight of them for her work in The Heiress (1949), Samson and Delilah (1949), All About Eve (1950), A Place in the Sun (1951), Roman Holiday (1953), Sabrina (1954), The Facts of Life (1960) and The Sting (1973).

The Country Girl

The Country Girl was a 1954 film written and directed by George Seaton and starring Bing Crosby, Grace Kelly and William Holden. Adapted by Seaton from Clifford Odets’ 1950 play of the same name, the film is about an alcoholic has-been actor who is given one last chance to resurrect his career.

Head designed the costumes for the film, transforming Kelly from her usual glamorous image to portray the worn-down character Georgie Elgin, the overwhelmed wife who had given herself up to prioritize caring for her alcoholic husband (played by Bing Crosby). The character’s “plain Jane” wardrobe included functional items like home-style belted dresses, cardigans, a green wraparound dress, a dark V-neck evening gown and a simple trench coat. It was all unlike anything audiences had seen Kelly wear on or off the big screen.

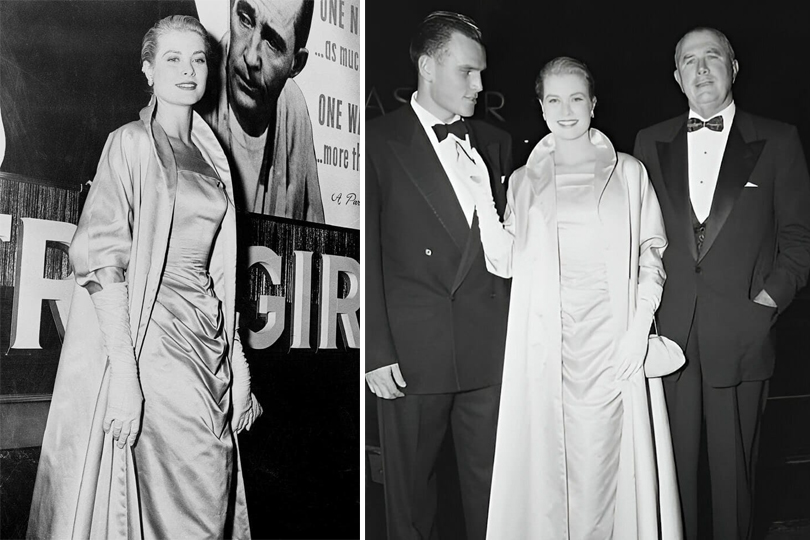

When the film had its premiere on December 11, 1954, at the Criterion Theatre in New York City, Kelly transformed back to her glamorous Hollywood image, wearing an ice-blue (sometimes described as sea-green) Grecian-style satin evening gown that Head had designed specifically for Kelly to wear for the occasion. Head’s creation would unexpectedly become the fashion moment that would ultimately seal Kelly’s status as a fashion icon.

The floor-length dress, which featured a matching tailored evening coat, featured an almost architectural neckline, a draped bodice and thin spaghetti straps, and was made from a bolt of French satin that reportedly cost $4,000. Kelly finished off the look with a pair of long white evening gloves.

“Edith Head was a costume designer rather than a couturier. Worn with elbow-length gloves and little other adornment, Grace Kelly set the bar for a new modern glamour and yet the colour is deliciously unorthodox,” said Jo Ellison, author of the book Vogue: The Gown.

The Country Girl was a box office success, and the film was ultimately nominated for seven Academy Awards, including a nomination for Kelly for Best Actress. Months after the premiere, Kelly would famously re-wear her premiere dress to the 27th annual Academy Awards, which were held on March 30, 1955, at the RKO Pantages Theatre in Hollywood. At the time, it was considered the most expensive dress ever worn on the Oscar red carpet.

Kelly won the Oscar that night, and kept her speech short and sweet: “The thrill of this moment keeps me from saying what I really feel. I can only say thank you with all my heart to all who made this possible for me. Thank you.”

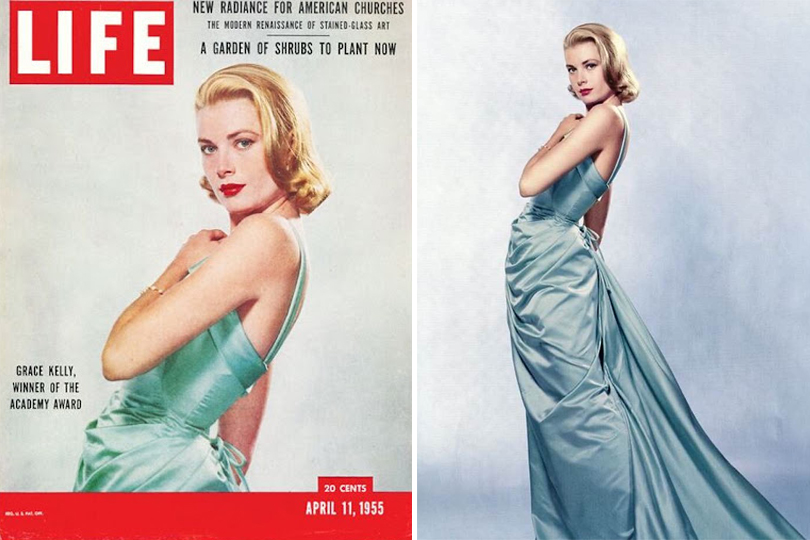

The dress would have one more memorable public outing just days after the Oscar ceremony. In celebration of her big win, Kelly wore the gown a third time when she was photographed by Philippe Halsman, which was used for the cover of the April 11, 1955, issue of Life magazine. This time the dress had an additional panel going across the bodice, and it was photographed without the matching floor-length evening coat that Kelly had previously worn. The cover was everywhere, and the photo shoot ultimately solidified Kelly’s status as a fashion icon in the public’s eye.

After that, Kelly set the standard for 1950s style and beyond. Decades later, the public was still obsessed with her style.… After all, Hermès did eventually rename their Sac à Dépêches (originally created in the 1920s) the Kelly bag after it was popularized by the Hollywood star turned Princess of Monaco.

The afterlife of the dress

Shortly after her defining Oscar moment, Kelly left Hollywood behind and married Rainier III, Prince of Monaco, in a two-day wedding extravaganza on April 18, 1956 (civil ceremony) and April 19, 1956 (religious ceremony) in Monaco. The Hollywood actress became a princess at the age of 26. She died on September 14, 1982, at age 52, following a car crash on a winding road in Monaco.

But Kelly’s ice-blue dress would live on, appearing in numerous fashion exhibitions across the globe throughout the years. It would also serve as an inspiration for countless designers and Hollywood starlets to come.… Think Kim Basinger’s mint-green Escada dress that she wore when she won Best Supporting Actress for L.A. Confidential in 1998, or Gwyneth Paltrow’s pink Ralph Lauren gown that she wore when she won Best Actress for Shakespeare in Love in 1999 (not so surprising considering Ralph Lauren has consistently hailed Kelly as his lifelong muse).

As for the gown’s designer, Head died just before her 84th birthday, on October 24, 1981. She remains a Hollywood legend and holds the Guinness World Record as the most-credited costume designer in film history, with a total of 432 credits. Unlike most other designers of her time, Head never undertook couture or wholesale fashion work, according to Hollywood Costume Design author David Chierichetti. Instead, she opted to “work only in the context of a certain actress in a certain film.”

Commenting in 1978 on her view of her profession, Head said:

“I think that most people don’t realize motion pictures are not ‘fashion.’ So many people say to me, ‘Isn’t it lovely to be a fashion designer and dress these beautiful stars?’ That is not what happens. I get a script, and the script says, ‘In this film, Grace Kelly is playing a princess, she’s beautiful, and she has fabulous clothes.’ The next script says, ‘Grace Kelly is a middle-aged, dowdy housewife’…so you do dowdy clothes. I can do tacky clothes, dowdy clothes, sexy clothes, horrible clothes…anything the world should want—male, female or animals…. Costume design is like theatre. Costume design is to tell a story. It has nothing to do with fashion at all, unless it is a fashion picture.”

Head may have believed that, but her work undeniably sculpted the future of Hollywood and the red carpet, especially the ice-blue satin confection worn by Kelly in 1955. Head’s genius wasn’t just that she could create beautiful clothes for the big screen. It’s that she could build an image so coherent it became a cultural memory—one ice-blue fold of satin at a time.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.