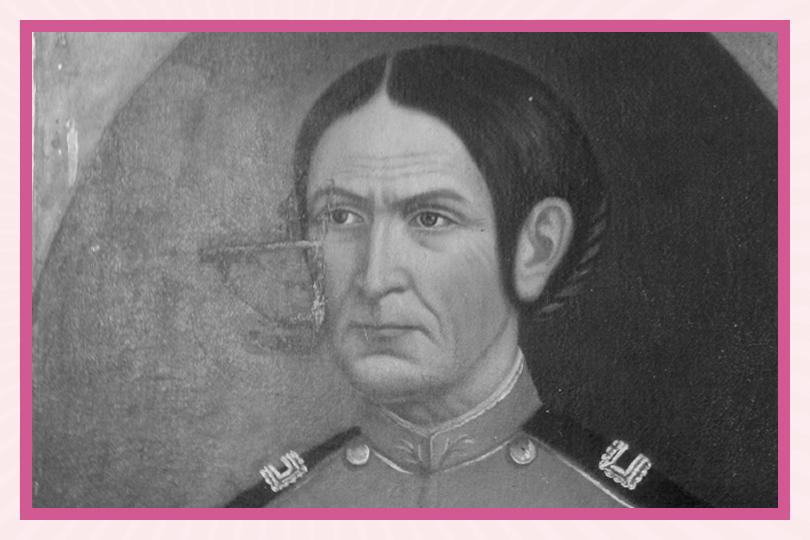

In 2013, the president of Argentina sparked controversy by replacing a towering monument of Christopher Columbus (a man previously celebrated for “discovering” the Americas but increasingly seen as a symbol of invasion and genocide) with a statue of a woman named Juana Azurduy. The statue depicts Juana in a fierce battle position, wielding a sword in mid-air, strikingly capturing her courage and military prowess. Though little-known to us, Juana was one of the first to sound the call to arms for independence in Latin America and is celebrated as a heroine of the nineteenth-century rebellion against Spanish rule. Read on for a look at her early life, her extraordinary military career, and her lasting legacy.

Early years

According to Dr Cheryl Jiménez Frei, a historian of Latin America, Juana Azurduy was born in 1780 in the village of Chuquisaca (today’s Sucre, in Bolivia). She was of mestiza (mixed) heritage, as her father was Spanish, and her mother was Indigenous.

Professors Catherine Davies, Claire Brewster, and Hilary Owen record that she received a basic convent education. Some sources claim that instead of reading stories of piety, “she preferred to learn about the exploits of chivalric heroes and the Crusaders.”

In 1805, after she left the convent, she married a soldier named Manual Padilla. Together, they had several children, and their marriage was seemingly one of equality and harmony. They were both strong supporters of the Latin American independence movement and began to collect money and arms in support of the cause.

First, Padilla enlisted in General Belgrano’s troops. Unfortunately, they lost the battle of Chuquisaca in January 1811. Luckily, Padilla escaped back home, and the family relocated to the town of La Laguna to regroup.

Guerilla fighter and mother of the wounded

In 1813, General Belgrano began to regroup and Padilla helped him by raising 10,000 soldiers. At this point, it is claimed that Juana was fed up with watching from the sidelines and wanted to share in the sacrifices that her husband was making and the risks he was taking. She therefore “resolved to become his compañera in danger and in glory.”

Juana soon joined the cause herself and became a guerrilla fighter in the wars for independence. While this might seem exceptional to us, that a woman was on the battlefield in the nineteenth century (a time usually associated with Victorian gender roles, during which women sat at home with their embroidery) as noted by Davies, Brewester, and Owen, she was not alone: they count at least 90 prominent female soldiers that fought against Spanish rule. But, they also go on to say that out of all of these women, Juana stands out as particularly exceptional.

She served under the Army of the North (fighting alongside her husband and sons) in the attempt to liberate areas of modern-day Argentina and Bolivia. She eventually went on to lead her own legion of male soldiers, ‘Los Leales,’ and a personal guard of female soldiers, the ‘Amazonas’ who fought alongside her.

Apparently, Juana, often donning her signature red jacket, was a very charismatic leader. Her troops respected her for her bravery and enthusiasm for the cause. They appreciated that she was always the first one on the battlefield and the last one to leave it. She “led them like a true commander.” But also, as a woman, she “loved them as a mother,” and “cured and comforted the wounded.” It is interesting that she cultivated this reputation balanced between “varonil power” and “feminine grace.”

Her troops saw many successes but also tragic defeats. In one battle, in 1816, her soldiers were left badly wounded, and many killed, and the royalists went in search of their leaders: Juana and her husband. Juana got away but they shot her husband. Devastated, she continued to fight to avenge Padilla’s death, even though she had been badly injured.

At around this time, Azurduy was honoured by General Belgrano and promoted to lieutenant colonel. She then had the right to wear a uniform and enjoy all the privileges of that rank.

Later years and legacy

In 1825, after Argentina achieved independence from Spanish rule, Juana retired from the military and returned to her home city of Chuquisaca. She was granted a pension, but unfortunately, political chaos and uncertainty made it so that her pension never actually made it to her. Tragically, after a life of bravery and patriotism, she died “a very humble death,” her heroism entirely forgotten, alone and in poverty, on May 26, 1862.

As noted by Davies, Brewster, and Owen, she was remembered as a heroine of the independence movement, a century later. Sucre’s airport Is now named Juana Azurduy de Padilla and one of the capital’s main streets is called Calle Azurduy.

Furthermore, Jiménez Frei notes that in 2009, Argentina’s president posthumously promoted Azurduy to general, and in 2010, she and the Bolivian President Evo Morales declared Azurduy’s date of birth (12 July) the Day of Argentine-Bolivian Fellowship. And, as we saw at the beginning of this article, the statue that replaced Columbus proudly shows that Juana is someone to celebrate and is integral to the nation’s identity. As one indigenous activist said, “to keep the image of Columbus there is to say we did not reject oppression. But to put Juana Azurduy there…is emancipation, to cut the chains.”