Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

Thousands of new perfumes are launched every year, but only one has truly stood the test of time, being as popular now as when it first went on sale almost a hundred years ago. Chanel No. 5, Mademoiselle Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel’s original fragrance for women, has consistently graced vanity tables around the world since its release in 1921, becoming synonymous with sophistication and luxury.

The legend of Chanel No. 5 was primarily based on stories that at one point were difficult to prove, but over the years historians have uncovered what is likely the true story behind the creation of the iconic fragrance. Here, we take a look at the story of the unique best-selling scent and some of the factors that have contributed to its unprecedented success.

Beginnings

It’s important to note that the story of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel’s life is filled with an endless number of discrepancies, which is a reflection both of her own inconsistencies and the inconsistent recording of them. While there are countless rumours and stories that surround the designer and her controversial life, biographers have come to agree on the main points.

Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel was born on August 19, 1883, in Saumur, Maine-et-Loire, France. Though today we know “Chanel” as an iconic luxury name, she was born into an impoverished family and her early years were anything but glamorous. At age 12, after the premature death of her mother Eugénie Jeanne Devolle Chanel (known as Jeanne), Gabrielle and her two sisters were placed in the Sisters of the Sacred Heart orphanage in Aubazine by her father, Henri-Albert Chanel, while her two brothers were sent to work as farm labourers with a local family. She was raised by nuns who taught her how to sew – a skill that would lead to her life’s work.

At the age of 18, Gabrielle left Aubazine and began working as a sales assistant in the Maison Grampayre shop in Moulins, while simultaneously working as a singer performing in cafés and clubs in Moulins and later in Vichy. It was during this time that she acquired the nickname “Coco.” There are varying accounts of its origins: according to biographers she got her legendary nickname from one of her signature songs “Qui qu’a vu Coco?” while she herself later claimed that it was a “shortened version of cocotte, the French word for ‘kept woman,’” which she was for a number of years.

Two men were instrumental in Mademoiselle Chanel’s first fashion venture. In her early 20s, she became involved with Étienne de Balsan, the son of textile entrepreneurs, and he helped her start a millinery business in Paris. She later left him for English aristocrat Captain Arthur Edward ‘Boy’ Capel, who she called her true love and who also partially funded her early career. In later years, Mademoiselle Chanel reminisced of this time in her life: “Two gentlemen were outbidding for my hot little body.”

In 1910, she opened a boutique selling hats at 21 rue Cambon, Paris, named Chanel Modes. She later added stores in Deauville and Biarritz as her career began to bloom and she began designing clothes. By the beginning of the 1920s, this young woman was a phenomenon in French fashion circles.

Sweet scents

Up until the 20th century, perfumers crafted scents while fashion designers created clothing. Although some designers and fashion houses began to dabble in scent production in the early 1900s, famed French couturier Paul Poiret (1879–1944), one of the great designers of the 20th century, is generally credited with being the first fashion designer to introduce a signature fragrance. Poiret released Parfums de Rosine in 1911, a fragrance he created with his wife and named after his daughter instead of using his own name.

By the early 1920s, Mademoiselle Chanel was ready to follow suit and take her thriving fashion business to new heights. She wanted to create a scent that could describe the new, modern woman she epitomized and designed for.

Perfume “is the unseen, unforgettable, ultimate accessory of fashion….that heralds your arrival and prolongs your departure,” she once explained.

The story of No. 5 starts during the late summer of 1920, when Mademoiselle Chanel went on holiday on the Cote d’Azur with her then-lover, the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich. There she met French-Russian chemist Ernest Beaux, a sophisticated and well-read perfumer who had worked for the Russian royal family and lived close by in Grasse, the centre of the perfume industry. Mademoiselle Chanel challenged him to create a signature scent for her that would make its wearer “smell like a woman, and not like a rose.”

Rather than create a simple floral scent or a single-note scent, as was de rigueur back in the ’20s, Beaux played with a mix of notes, and months later presented Mademoiselle Chanel with small glass vials containing sample scents numbered 1 to 5 and 20 to 24 for her assessment. As legend goes, she picked the fifth vial, her choice inspired (some say) by her belief that the number five was magical. “I show my collections on the fifth of May, the fifth month of the year, so let’s leave the number it bears, and this number five will bring it good luck,” she declared.

The chosen formula, which debuted in 1921 alongside her latest collection, was a bouquet of notes that included jasmine, ylang-ylang, may rose and sandalwood…along with one last abstract ingredient that had never been used before in perfumery. In the fifth sample, Beaux had bravely added a generous dosage of aldehydes, an unusual synthetic component that would exaggerate the notes and give No. 5 its distinctive “clean” scent, reminiscent of fresh laundry.

Of course, it is rumoured that the concoction was actually the result of a laboratory mistake after Beaux’s assistant added it by accident. Regardless, the perfume’s strong percentage of aldehydes meant that the fragrance would ultimately linger on the wearer’s skin for an extended period of time, making it more suitable for “modern” women with busy lives and complex tastes.

Mademoiselle Chanel later said, “It was what I was waiting for. A perfume like nothing else. A woman’s perfume, with the scent of a woman.”

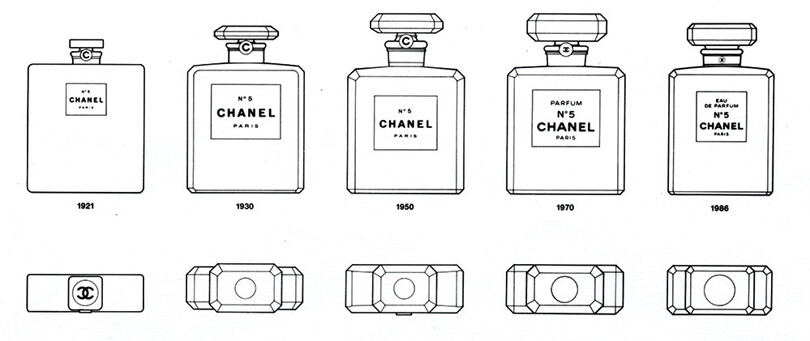

Then there was the elegant rectangular design of the bottle, an important part of the perfume’s universal allure. Some say that the inspiration for the bottle was drawn from glass pharmaceutical vials, but the No. 5 bottle was more than likely designed at Mademoiselle Chanel’s request to resemble a whisky decanter in “exquisite, expensive, delicate glass.” It was the whisky decanter, one she always admired, that was favoured by her dead lover, Capel, who had died tragically in 1919. The austere bottle was given a minimalist white label with black sans serif text emblazoned on it. On top, the perfume was sealed with a diamond stopper, inspired by the Place Vendôme in Paris.

The first bottle, produced in 1921, differed slightly from the Chanel No. 5 bottle known today. The original container had small, delicate, rounded shoulders and was sold only in Chanel boutiques to select clients. A few years later, when “Parfums Chanel” incorporated, the glass proved too thin to survive shipping and distribution, so the bottle was modified with thicker glass and square, faceted corners – the only significant design change in its history.

At first, Mademoiselle Chanel planned to give No. 5 free of charge as a Christmas gift to selected customers of her fashion house. But she realized its full business potential as soon as she saw the great enthusiasm it met with when she first presented the fragrance in her Paris boutique on May 5, 1921, alongside her latest fashion collection.

Business dealings and anti-Semitism

Chanel No. 5 was an instant hit with Mademoiselle Chanel’s customers, but it was made in incredibly limited amounts in Beaux’s laboratories. Théophile Bader, the founder of the department store Galeries Lafayette, wanted to sell No. 5, so he introduced Mademoiselle Chanel to businessmen Pierre and Paul Wertheimer (she developed a close friendship with Pierre, something she would later come to regret).

In 1924, the four negotiated a deal creating a new corporate entity, Parfums Chanel. Under the deal, the Wertheimers agreed to manage production at their factories as well as marketing and distribution of the perfume, for which they would receive 70 per cent of the profits, while Bader, who would also assist with distribution, would receive 20 per cent as a finder’s fee. Mademoiselle Chanel herself would receive a mere 10 per cent.

Feeling she had been cheated, Mademoiselle Chanel filed a lawsuit trying to get more control of the company and more of the profits. Over the years, as No. 5 became immensely popular and a massive source of revenue, she repeatedly sued to have the terms of the deal renegotiated and spent more than 20 years trying to gain full control of Parfums Chanel. In fact, according to Axel Madsen in the biography Chanel: A Woman of Her Own, by 1928 the Wertheimers had a lawyer on their staff who dealt solely with the designer, while she claimed that Pierre Wertheimer was “the bandit who screwed me.”

Not everything about the history of Chanel No. 5 is luxurious, and it’s no secret that Mademoiselle Chanel had some very questionable opinions and alliances throughout her lifetime. During World War II, she not only had a long affair with a senior Nazi officer and agreed to be a spy in the service of the Third Reich, she also decided to exploit the Nazi laws in an attempt to gain sole control of Parfums Chanel from the Wertheimers. Since the Wertheimer brothers were Jewish, their business and ownership was susceptible to Nazi seizure, and the upsurge in anti-Semitism saw the designer using the ‘Aryan’ laws and all of her connections with senior Nazi officials to try to transfer into her hands – in effect, to steal – the company from the brothers.

This attempt failed, as she learned that the Wertheimers had transferred control of the company to a non-Jewish Frenchman named Félix Amiot before fleeing to the United States. After the war, when authorities in Paris began prosecuting Nazi collaborators, she was summoned for questioning and it was only thanks to Winston Churchill, who intervened on her behalf, that she was released without being punished for her behaviour. According to Hal Vaughan’s book Sleeping with the Enemy, she also took care to erase, wherever possible, all evidence of her actions. Ultimately, Mademoiselle Chanel never endured any consequences for her wartime dealings with the Nazis.

The Wertheimers regained ownership of Parfums Chanel, and renegotiated the original 1924 contract with Mademoiselle Chanel to grant her two per cent of worldwide perfume sales, making her one of the richest women in the world. She made a celebrated return to the fashion world in 1954, aided by the brothers, who stayed silent on her previous Nazi ties, recognizing that exposing her would ultimately destroy the business venture for everyone involved. In fact, most people are unaware of Mademoiselle Chanel’s controversial past and involvement with the Nazi party.

Marketing genius

Chanel No. 5 was an instant success, partly due to some of Mademoiselle Chanel’s newfound fame and ingenious marketing tricks. Initially, according to the film The No. 5 War, she told her customers to sprinkle the perfume on their bodies wherever they wanted to be kissed.

In 1937, she changed the face of fragrance advertising by using her own image to promote No. 5 (and herself) in Harper’s Bazaar. In the magazine – which came out in the midst of a worldwide depression – she appeared in her full glamour, telling the world she was the living epitome of the luxury fragrance.

The extravagant ad worked, and advertising became a key factor in the brand’s ongoing success. The perfume went on to be featured in glamorous advertisements throughout the 1940s and 1950s, using taglines like “Every Woman Alive Loves Chanel No. 5.” But arguably the best publicity that No. 5 ever received was not an advertisement at all.

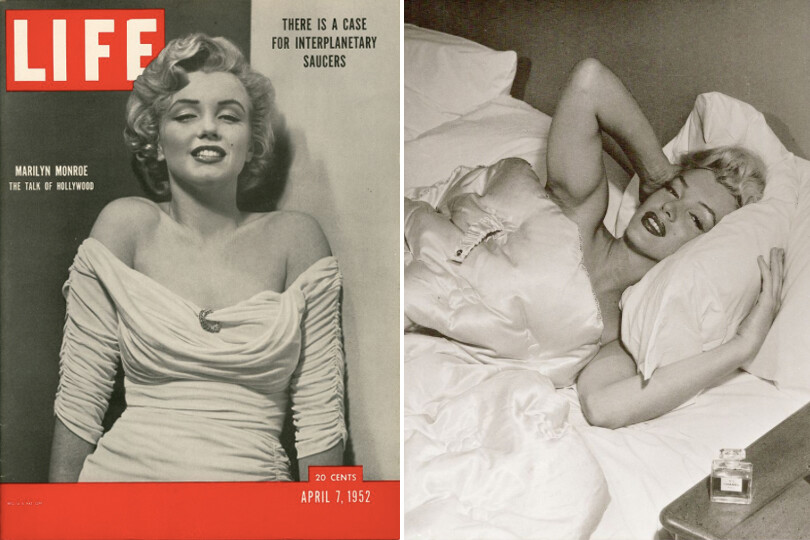

In April 1952, Marilyn Monroe singlehandedly changed the perception of the perfume when she appeared on the cover of Life for the first time. When asked by a reporter what she wore to bed, Monroe replied that she wore “five drops of Chanel No. 5” and nothing else. “I don’t want to say nude,” she said, “but it’s the truth.”

A second unsolicited endorsement came from Monroe during a photo shoot for an article by Sidney Skolsky in Modern Screen in 1953; a Chanel No. 5 bottle is seen on Monroe’s nightstand.

After Monroe’s sexy quip, Chanel recognized the power of celebrity endorsement, and through the years the brand would go on to sign Hollywood’s most recognizable faces, including Monroe. French actress Catherine Deneuve signed on to be the face of the fragrance in 1969, a partnership she held for the next 10 years, followed by Carole Bouquet, Candice Bergen, Lauren Hutton, and later Nicole Kidman, Audrey Tautou, Brad Pitt (the first male to advertise the scent), Gisele Bundchen, Lily-Rose Depp and, most recently, Marion Cotillard.

Celebrity endorsements and advertising played a role in creating and maintaining the luxurious allure and popularity of the fragrance. No. 5 was even the first fragrance to ever advertise during the Super Bowl half-time show.

In 1980, Andy Warhol cemented No. 5’s iconic status with his pop-art, silkscreen series entitled “Ads: Chanel.” Warhol’s depictions of the fragrance bottle were then re-purposed by Chanel in their high-profile advertising campaigns.

Today

Mademoiselle Chanel died on January 10, 1971, in her room at the Hotel Ritz in Paris, where she had resided for more than 30 years. She was 87 and still designing at the time of her death. After a period of time, Jacques Wertheimer bought the controlling interest in the House of Chanel, but by 1974, the company had dwindled, and only the perfume line and the original shop on rue Cambon remained.

In 1974, Wertheimer’s son Jacques assumed control of the company and revamped it by focusing on the legacy and popularity of Chanel No. 5. The brand returned to Chanel’s previous celebrity-centric ads (Wertheimer’s first ads featured Audrey Tautou) and by 1983 Wertheimer had persuaded German designer Karl Lagerfeld to end his contract with fashion house Chloé and take over as chief designer for Chanel. Lagerfeld’s mandate was to resurrect the label to its former glory, which he did in record time.

Today Chanel No. 5 remains a household name, just as it was after its introduction, popular with a wide range of age groups. The popularity is partially thanks to the brand’s remarkable marketing, which reinforces Mademoiselle Chanel’s mythic aura. That decision has paid off as the rich story of Chanel No. 5 continues on…the legacy, fame, style and sales (one bottle is sold every 30 seconds) still unprecedented.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.