By Christopher Turner

The story of Lizzie Borden is one of the most notorious in American criminal history – equal parts gruesome and enigmatic. On a sweltering morning in August 1892, Andrew and Abby Borden were found brutally murdered in their home in the quiet mill town of Fall River, Massachusetts – both struck multiple times with a hatchet. The prime suspect? Their 32-year-old daughter, Lizzie Borden, a churchgoing spinster with a calm demeanour and an inconsistent alibi.

Lizzie quickly became the prime suspect and her trial in 1893 was a national sensation: the O.J. Simpson case of its day, with reporters flocking to Fall River to cover the gruesome murders. Lizzie’s calm composure, her churchgoing reputation, and the absence of any physical evidence ultimately led to her acquittal, yet public opinion never fully exonerated her. She lived the rest of her life in relative isolation, ostracized by her community.

More than a century later, the chilling case endures as a haunting symbol of Americans’ fascination with female violence, class privilege, and the blurred line between innocence and guilt. Was Lizzie the monster that modern headlines made her out to be…or the victim of patriarchal hysteria, tried as much for her defiance as for the crime itself? Here’s a look back at Lizzie Borden, America’s first true-crime obsession.

Lizzie Borden’s early years

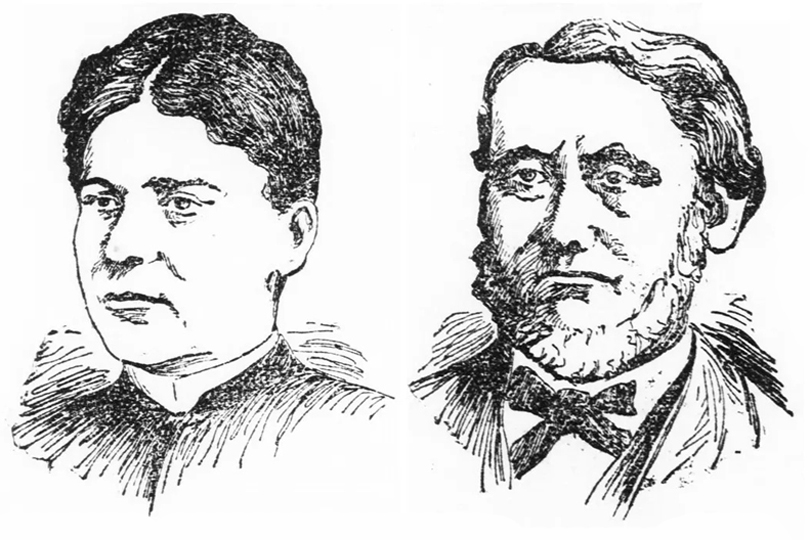

Lizzie Andrew Borden was born on July 19, 1860, in Fall River, Massachusetts, a textile mill town 50 miles south of Boston, to a wealthy yet notoriously frugal businessman, Andrew Jackson Borden (1822–1892) and Sarah Anthony (née Morse, 1823–1863). Lizzie was the third child born to the couple: ahead of her were Emma Lenora, and Alice Esther, who died at 22 months of hydrocephalus (also commonly referred to as water on the brain).

Lizzie’s mother, Sarah, died of uterine congestion and spinal disease on March 26, 1863, when she was 39 years old. On June 6, 1865, two years and two months after his first wife’s death, Andrew married Abby Durfee Gray (1828–1892), a woman he had met at the Central Congregational Church. Abby was 37 at the time, and Andrew was 42. Lizzie later stated that she called her stepmother “Mrs. Borden,” and while she claimed that the two had a cordial relationship, she believed that Abby had married her father for his money.

Lizzie and her older sister Emma had a relatively religious upbringing, and as a young woman, Lizzie was very involved with religious organizations and activities at her local church, including teaching Sunday school to children of recent immigrants.

The murders of Andrew and Abby Borden

Tension had been growing within the Borden family throughout the first half of 1892, mostly over Lizzie and Emma’s disapproval over Andrew’s gifts of real estate to various members of Abby’s family. Then, at the beginning of August 1982, the entire family became violently ill. A family friend later speculated that their illness was caused by mutton that had been left on the stove to use in meals over several days. Abby, however, voiced a fear to friends and family that the household had been purposely poisoned, given that Andrew was not a popular man in Fall River.

On August 4, 1892, Andrew (then 69) and Abby (then 64) were found brutally murdered in their home at 92 Second Street in Fall River. Their deaths occurred in separate locations in the house. Andrew was discovered, unrecognizable, in a pool of blood on the living room couch, his face nearly split in two after 10 or 11 blows with a hatchet (not an axe, which through the years has become part of the murder’s mythology). Abby was found upstairs in the guest room, her head smashed to pieces after 19 blows with the same hatchet (again, not an axe); it was later determined that she had been killed at least 90 minutes earlier than her husband.

The bodies were discovered by different people at different times. According to court records, Bridget (“Maggie”) Sullivan, the maid at the Borden family residence, was upstairs just after 11 am when she heard a cry from Lizzie, who had discovered her father’s body when she entered the house: “Maggie, come down! Come down quick. Father’s dead; somebody came in and killed him.”

A half hour or so after Andrew’s body had been discovered and the downstairs had been searched by police for evidence of an intruder, Adelaide Churchill (a neighbour who had come to comfort Lizzie) made the grisly discovery of Abby’s body on the second floor of the Borden home. Adelaide and Bridget were searching the house at Lizzie’s suggestion.

After the discovery of the bodies, Dr. Bowen (the family’s physician, who lived across the street) came over to pronounce both victims dead. Word quickly spread across the town that an assassin had struck the victims in broad daylight at their home on a busy street, one block from the town’s business district.

The Fall River Herald reported that neighbours and passers-by had heard nothing at the Borden property, and there was no evident motive like robbery or sexual assault. Initial speculation as to the identity of the murderer centred on a “Portuguese labourer” (whose name was Jose Correa de Mello) who had visited the Borden home earlier in the morning and “asked for the wages due him,” only to be told by Andrew that he had no money and “to call later.”

That story didn’t last long. Two days after the murders, newspapers began reporting that Lizzie, who was 32 at the time, might have had something to do with her father’s and stepmother’s murders.

A story in the Boston Daily Globe reported rumours that “Lizzie and her stepmother never got along together peacefully, and that for a considerable time back they have not spoken,” but noted also that family members insisted relations between the two women were quite normal. The Boston Herald, meanwhile, viewed Lizzie as above suspicion: “From the consensus of opinion it can be said: In Lizzie Borden’s life there is not one unmaidenly nor a single deliberately unkind act.”

An initial inquest hearing was held less than a week after the murders, on August 9, in the courtroom over police headquarters; Lizzie attended, after being prescribed doses of morphine by Dr. Bowen to calm her nerves. During the hearing, Lizzie continuously contradicted herself, providing differing accounts of the morning in question. The inquest adjourned two days later, on August 11, and Lizzie was served with a warrant of arrest and then jailed for the double homicide.

The next day, Lizzie entered a plea of “Not guilty” to the charges of murder and was transported by rail car to the jail in Taunton, eight miles north of Fall River, where she was confined to a 9.5-by-7.5-foot cell for the next nine months. Lizzie did briefly leave her cell on August 22, when she returned to a Fall River courtroom for her preliminary hearing. At the end of that hearing, Judge Josiah Blaisdell pronounced her “probably guilty” and ordered her to face a grand jury for the murder of Andrew and Abby Borden. A grand jury began hearing evidence on November 7, and Lizzie was indicted on December 2.

Lizzie’s trial would be next. As a result of the crime’s sensational nature, her trial attracted national attention, and her name was whispered with fear and fascination across the country.

The trial of the century

Lizzie’s trial began on June 5, 1893, in a New Bedford courthouse before a panel of three judges and a jury of 12 men (half of the jurors were farmers; others were tradesmen). The trial was a landmark in publicity and public interest.

Because Abby was ruled to have died before Andrew, her estate went first to Andrew and then, at his death, to his daughters Lizzie and Emma as part of his estate. A considerable settlement, however, was paid to settle claims by Abby’s family. Still, Lizzie could afford the best legal team to defend her with her father’s money in hand. Andrew V. Jennings, Melvin O. Adams and former Massachusetts Governor George D. Robinson represented the defendant, while Hosea M. Knowlton and future United States Supreme Court Justice William H. Moody argued the case for the prosecution.

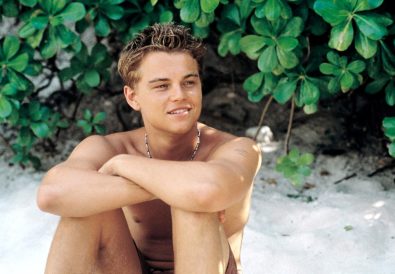

Lizzie’s lawyers advised her to dress in head-to-toe black throughout her trial. Lizzie presented herself in court as a helpless maiden, appearing in a tightly corseted black dress, and came to the courthouse holding a bouquet of flowers in one hand and a fan in the other. One newspaper described her as “quiet, modest and well-bred,” far from a “brawny, big, muscular, hard-faced, coarse-looking girl.” Another stressed that she lacked “Amazonian proportions” and that she could not possess the physical strength, let alone the moral degeneracy, to wield a weapon with skull-cracking force.

Reporters flocked to Fall River, and the trial quickly became a media spectacle, with newspapers across North America calling it “the trial of the century,” spinning lurid headlines that painted Lizzie as either a cold-blooded killer or a misunderstood woman trapped by the suffocating gender roles of the Victorian era. Reporters obsessed over her composure, her tailored black dresses and her refusal to break down in court. To some, her poise signalled guilt, while others saw it as a reflection of the quiet dignity of a churchgoing woman wrongly accused.

As for the logistics presented at the trial, Lizzie claimed that she was in the barn at the time of the murders and said she had entered the house later that morning to find her father dead in the living room. The evidence that the prosecution presented against Lizzie was circumstantial at best. It was alleged that she had tried to buy poison the day before the murders and that she burned one of her dresses several days afterwards. Although fingerprint testing was becoming commonplace in Europe at the time, the Fall River police were wary of its reliability, and refused to test for prints on the potential murder weapon – a hatchet – found in the Bordens’ basement.

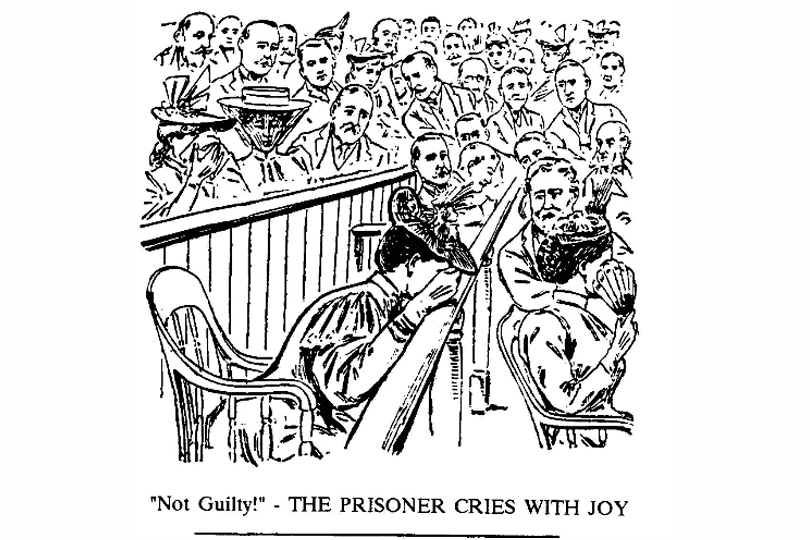

After nearly two weeks of sensationalistic courtroom drama, the jury was sent to deliberate on June 20, 1893. Despite inconsistent testimony and the suspiciously timed attempt to purchase poison before the murders, after an hour and a half of deliberation, the jury came back to the courtroom and acquitted Lizzie of both murders. Her acquittal was largely due to a lack of physical evidence, coupled with her well-bred Christian persona and an all-male jury reluctant to believe a “proper lady” capable of such violence.

After the foreman of the jury announced, “Not guilty,” Lizzie reportedly let out a yell and sank into her chair, resting her hands on a courtroom rail with her face in her hands, and then let out a second cry of joy. Soon, her sister Emma, her counsel, and courtroom spectators were rushing to congratulate her. Lizzie hid her face in her sister’s arms and announced, “Now take me home. I want to go to the old place and go at once tonight.” The courtroom audience cheered her acquittal. Upon exiting the courthouse, Lizzie told reporters that she was “the happiest woman in the world.”

Newspapers across North America generally praised the jury’s “Not guilty” verdict. The New York Times, for example, editorialized: “It will be a certain relief to every right-minded man or woman who has followed the case to learn that the jury at New Bedford has not only acquitted Miss Lizzie Borden of the atrocious crime with which she was charged, but has done so with a promptness that was very significant.” The Times added that it considered the verdict “a condemnation of the police authorities of Fall River who secured the indictment and have conducted the trial.” Not stopping there, The Times editorialist blasted the “vanity of ignorant and untrained men charged with the detection of crime” in smaller cities; the police in Fall River, the editorial concluded, are “the usual inept and stupid and muddle-headed sort that such towns manage to get for themselves.”

But the verdict didn’t mean the nightmare was over. Lizzie may have been acquitted, but when she returned home to Fall River, she found her life was altered forever, as friends and neighbours began to shun her. Her calm composure, her churchgoing reputation, and the absence of any physical evidence may have ultimately led to her acquittal, but public opinion never fully exonerated her.

Two months after the verdict, the Borden sisters moved to a large Victorian house, which they called “Maplecroft,” located on the corner of French Street and Belmont Street in The Hill neighborhood of Fall River. Lizzie withdrew to her new home, but even there, neighbourhood children still pestered the Borden sisters with pranks.

Lizzie and Emma had a falling out in 1904 (more on that later), and Emma ultimately left Maplecroft in 1905. The sisters never saw each other again, and Lizzie became even more of a recluse, rarely leaving her home. She even began using the name Lizbeth A. Borden, in an attempt to distance herself from her past.

Lizzie became ill following the removal of her gallbladder, and died of pneumonia at the age of 66 on June 1, 1927, in Fall River. Funeral details were not published, but it is known that only a few people attended her funeral. Her sister Emma died nine days later at a nursing home in Newmarket, New Hampshire, at the age of 76 after suffering from chronic nephritis. Both lifelong spinsters, Lizzie and Emma were buried side by side in the family plot at Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River, the same plot as their father and stepmother.

Was Lizzie Borden a lesbian?

Persistent rumours over the years have suggested that Lizzie Borden was a lesbian. There is no definitive evidence of this, but nonetheless the rumour has stuck throughout the years with true-crime fans. The idea that Lizzie was a lesbian has mostly been fuelled by her decision never to marry, suggestions that she had a relationship with her family maid Bridget Sullivan, and her close relationship in later years with stage actress Nance O’Neil.

In the 1984 novel Lizzie, crime novelist Ed McBain floated the possibility that Lizzie was secretly a lesbian and may have been having an affair with Bridget. In McBain’s opinion, when Andrew and Abby found out about the affair, their reaction drove Lizzie to murder them – either out of rage or to hide her secret, or both. The 2018 film Lizzie, starring Chloë Sevigny and Kristen Stewart, cemented the lesbian theory in pop culture with its portrayal of a love affair between Lizzie and Bridget, even though the film was not based on historical fact.

Then there are the theories that Lizzie had another lesbian relationship. Although both she and Emma were reclusive in the years after the trial, sticking to their house in The Hill neighbourhood of Fall River, Lizzie did make friends with a stage actress named Nance O’Neill. According to news reports at the time, Emma did not approve of the friendship, which was the main reason she eventually moved out of the house in 1905, and never spoke to Lizzie again. Rumours that Lizzie and Nance had a sexual relationship swirled as a result.

While the notion that Bridget and Lizzie were having an affair is basically pure fan fiction, the possibility that Lizzie had a real romantic relationship with Nance – who publicly identified as a lesbian – is much more likely. That there was a relationship is based on rumour and conjecture, with no direct evidence to support it. It is, of course, very possible for two women to have a close relationship that has nothing to do with romance, but the friendship between the two women helped bolster the lesbian theory into what it is today.

Although we’ll never really know the truth, public opinion remains convinced that Lizzie did kill her parents. While money and a desire for freedom are considered the most likely motives, it’s no surprise, given how “deviant” sexuality has been portrayed over the last century, that the dominant theory remains that Lizzie Borden was an axe-murdering lesbian.

The Lizzie Borden allure

As time passes and the truth gets further and further away, the story becomes riper for interpretation. Today finer details of both the murders and Lizzie’s life are disputed, exacerbated by the time-worn legend of the original crime and the lack of accurate records. Lizzie Borden has become a lasting pop culture figure, and her story has been adapted into numerous movies, documentaries, TV shows, books, musicals, plays, a ballet, a rock opera, and the upcoming Netflix series Monster: Lizzie Borden (created by Ryan Murphy and starring Ella Beatty as Lizzie). Her story is even the basis of the popular skipping-rope rhyme (even though the details are wrong): “Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother 40 whacks. When she saw what she had done, she gave her father 41.” Remember, the Bordens received 29 whacks, not the 81 suggested by the famous ditty, but the popularity of the rhyme is a testament to the public’s fascination with the 1893 murder.

Today, the house where the Borden murders occurred is a bed and breakfast and museum, offering tours and overnight stays. The house has been restored to look as it did in the 1890s, with many original furnishings and original decor, and it is considered one of the most haunted places in North America. Maplecroft, the Victorian house that Lizzie and her sister purchased after the murders and where Lizzie lived until her death, is now a private residence and is not open to the public.

Was Lizzie the monster that today’s headlines make her out to be…or the victim of patriarchal hysteria, tried as much for her defiance as for the crime itself? The truth may remain forever trapped inside that infamous Fall River house, but one thing is certain. Lizzie Borden became something larger than life: America’s first true-crime obsession.

RELATED: