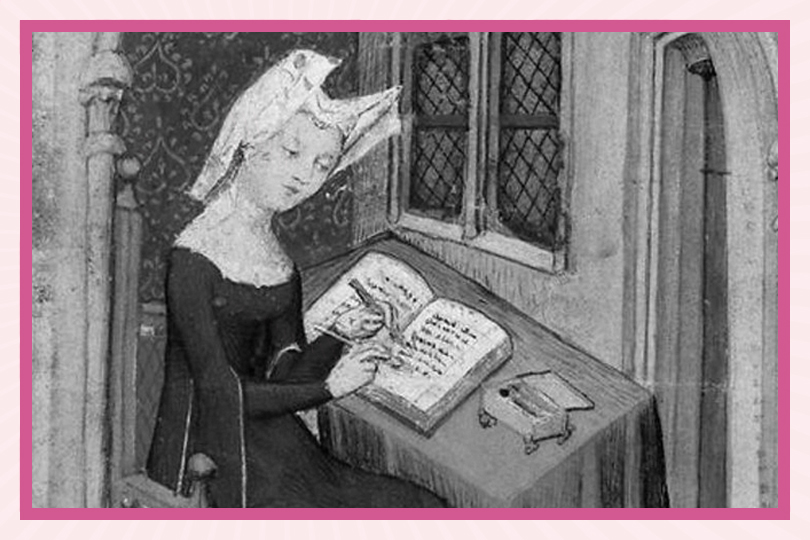

We often credit the twentieth—or even the nineteenth—century with the birth of feminism. However, if we go all the way back to the fourteenth century, we will find an extraordinary woman who was ahead of her time when she picked up her pen to promote gender equality: Christine de Pizan. As a poet, biographer, and all-around literary superstar, Christine left an impressive body of work behind. And yet today, so many people have never heard of her.

According to Professor Earl Jeffrey Richard, an expert on her life and work, Christine is “at once one of the outstanding writers of world literature and one of the most neglected.” To help rectify this, in this latest installment of our HER STORY column, we’re bringing you a glimpse into the life and legacy of this hugely influential yet underrated medieval feminist writer.

The Early Years

Christine de Pizan (also spelled Christine de Pisan) was born in Venice, Italy, in 1364. Her father, Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano, was widely recognized as a learned man. A few years after her birth, he was invited by Charles V, King of France, to take on the position of court astrologer. Tommaso accepted, and the family moved to France.

This meant that Christine would be raised at the French court, surrounded by the brightest minds and with access to great repositories of important manuscripts. And contrary to the social norms of the time, Tommaso encouraged all three of his children to get an education—even his daughter. Interestingly, this was apparently in contradiction to her mother’s wishes, who thought that she should focus on learning the usual feminine skills required to take care of the home.

Christine and her two younger brothers received formal educations at court and she was taught lessons in both Greek and Latin, great works of literature, history, philosophy, and medicine. Furthermore, she continued to read independently, teaching herself and soaking in knowledge. Christine was noticed from a young age as having a distinct literary flair, and the inner circle at court was charmed by the ballads and poems that she composed.

When she was around 15 years old, Christine was married to a court notary or secretary named Estienne de Castel. Though this was an arranged match, and he was 10 years her senior, her marriage was, according to her own later account, extraordinarily happy. Her husband encouraged her learning and literary activity and together they had three children.

Unfortunately, this is where her story takes a tragic turn.

Christine’s father died in 1388, and a year later, her husband died from the plague. At 25 years old, Christine was left alone as a widow with three young children to support and no means to do so.

But instead of remarrying, as was the convention of the day for financially vulnerable widows, she turned to her own devices: she picked up her pen.

As she later wrote in her journal: “I had to become a man.”

Lady of Letters

In 1393, Christine published her first book, One Hundred Ballads, thereby launching her career as a professional writer—the first woman to make a living from her writing, as noted by many scholars. According to Richards, writing was “a vocation she pursued with remarkable courage and energy as well as ambition.”

When she presented her work to the French court, she was met with great approval and in turn began to receive the support of financial backers. Her patrons included the most important figures of the era, such as: John, Duke of Berry; Philip the Bold; John the Fearless; Louis of Orleans; Charles VI and his wife Isabelle of Bavaria. She was therefore intimately involved in political events and had direct access to the inner royal circle.

In 1399, she published Letter of Othea to Hector, which was the medieval equivalent of a bestseller. In it, the goddess Othea taught the legendary hero Hector of Troy lessons in government and virtue. This was an early foray into the girl-power texts that she would produce in the future and that she would be remembered for.

During her life, she was recognized as an accomplished lyric poet and served as the official royal biographer of King Charles V. Christine also attacked contemporary (male-authored) literature that she felt misrepresented women, becoming engaged in hot-button cultural conversations of the time.

She published many works over the course of her career, but perhaps her best-known work, revered as a revolutionary and proto-feminist treatise, is The Book of the City of Ladies, published in 1405. Historian Eileen Power writes in Medieval Women that this text helped launch a more general debate in the French court about the status of women. Christine argued that women’s inferior position was not natural, but cultural. This might be obvious to readers today, but this was not the case in the Middle Ages. In fact, Richards argues that “within the context of her time, Christine’s thought must be viewed as revolutionary.”

The Later Years and Legacy

Christine lived during the Hundred Year’s War (1337-1453), a longstanding conflict between England and France. While the details of this conflict are outside the scope of this article, it is important to mention that the ups and downs of it affected her life and career.

In 1415, the English invaded France, and this prompted Christine’s retirement. She took refuge in a convent in Poissy, where years earlier her daughter had taken her vows, withdrawing from court and putting down her pen for many years.

But after the French victory in 1429 led by Joan of Arc, Christine was inspired to pick up her pen once again and authored her last work: “The Tale of Joan of Arc.” Christine’s account of the triumphant teenage girl known as the “Maid of Orleans” was the first to celebrate this national heroine, and the only work penned during Joan’s short lifetime.

It seems fitting that her last work celebrated a powerful female figure who victoriously led men into battle.

Christine died sometime around 1430, a year later.

Her work remained popular after her death and spread to other nations. For example, five of Christine’s works were translated into English in the fifteenth century. According to Henrietta Leyser in Medieval Women: A Social History of Women in England 450-1500, her children’s book The Moral Proverbs of Christine, published by Caxton in 1478, is credited as the first book by a woman to be printed in England.

Christine’s books declined in popularity after the Renaissance and it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that she was rediscovered. Now, she is seen as a feminist icon and her books are a common part of Women’s Studies curriculums at universities, but in the wider public, she is relatively unknown.

It’s time that she was recognized for her influential work and her forward-thinking belief in the equality of men and women.