By Christopher Turner

In the hauntingly floral pages of gothic fiction, no name blooms quite like V.C. Andrews. With her signature mix of taboo, tragedy and tightly wound family secrets, Andrews carved a literary legacy that feels as unsettling as it is addictive. Her most famous series, the Dollanganger family series, starts off with her best-known and most-loved work, Flowers in the Attic, the 1979 book that has been enjoyed by readers for more than 46 years and has sold millions of copies around the world. But behind that iconic saga lies a story as strange and enigmatic as the attic itself.

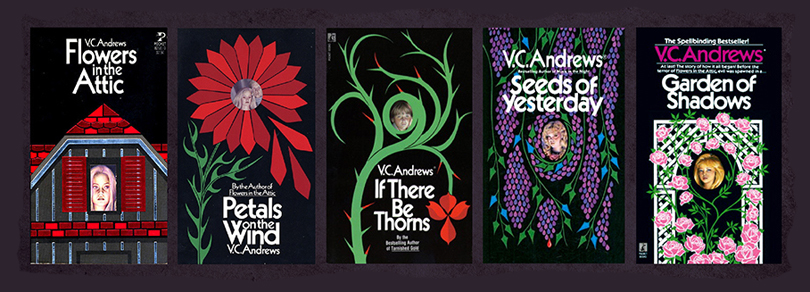

Flowers in the Attic, which was followed by Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns, Seeds of Yesterday and the Garden of Shadows prequel, turned Andrews into a bestselling phenomenon. Now an 11-book series, the gothic horror saga initially tells the story of four siblings who spend three years locked in the attic of Foxworth Hall, their grandparents’ mansion in Virginia, while their mother tries to win back her inheritance. It famously shocked readers with pages filled with child abuse, religious fanaticism, rape and incest. And that was just the beginning of the over-the-top saga.

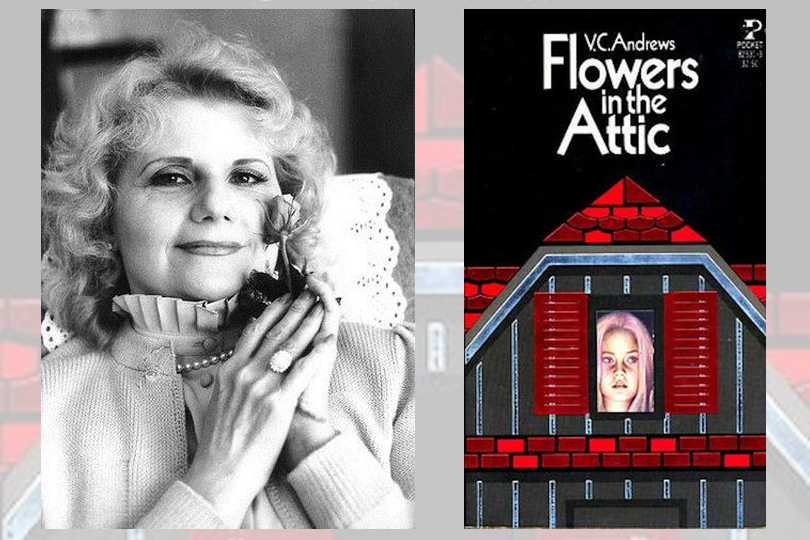

The Flowers in the Attic series is so outlandish, readers have long wondered if Andrews based any of the stories on her own life. After all, the famously reclusive author was a platinum blonde beauty bound to a wheelchair, her watchful mother permanently at her side at all of her public appearances.

Here’s the inside scoop on V.C. Andrews and her iconic Flowers in the Attic saga.

The woman behind the pseudonym

Before she became V.C. Andrews – queen of gothic family drama – she was Cleo Virginia Andrews, born in Portsmouth, Virginia, on June 6, 1923. The youngest child and only daughter of Lillian Lilnora (Parker), a telephone operator, and William Henry Andrews, a tool-and-die maker, she had two older brothers, William Jr. and Eugene.

Andrews grew up attending Southern Baptist and Methodist churches with her family in Virginia. A lifelong Southerner with a fiercely creative mind, she was a talented painter and commercial artist long before she sat down to a typewriter in earnest. But her life was marked by hardship: there are conflicting stories, most because of discrepancies from Andrews herself, but it is widely believed that a fall down a school staircase in her teens aggravated an existing arthritic condition and left her with chronic pain and limited mobility. She went through different surgeries after her fall and was at one point put in a full-body cast, which only made things worse. After the cast was taken off, Andrews suffered from crippling arthritis that required her to use crutches and a wheelchair for the rest of her life, which as a young woman often left her retreating into her inner world. School records show that Andrews had to leave Woodrow Wilson High School in Portsmouth in October 1940, in her senior year. The records note “health reasons.”

In a number of interviews given after she found fame, Andrews shared that she suffered from pain caused by bone spurs that formed on her spine. However, she also shared some pretty outrageous stories about her condition – like in the 1981 Washington Post article “Blooms of Darkness,” where she told a story about a surgeon who had a stroke while operating on her.

“I can have corrective surgery, but I’m a little leery of doctors because they made mistakes with me. One doctor had a small stroke while he was operating. The saw slipped and he cut off the socket of my right hip.… I have to have a new replacement. But the operation is very serious for me, life-threatening. I’m not in pain now…”

Andrews was known to deliberately exaggerate to confuse reporters, so how much of this was a dramatization is up for debate. But we do know that Andrews’ disability remained a real mystery for some time, and is misunderstood even now.

What is known is that after her accident at school, Andrews became completely dependent on her parents – and that dependency, as well as Andrews’ medical condition, brought a lot of shame to her mother, in particular.

“Let’s not allow anyone to see my ‘afflicted daughter,’” Lillian Andrews reportedly said about her wheelchair-confined daughter. This is according to a cousin of Andrews who went on record in the 2022 book The Woman Beyond the Attic: The V.C. Andrews Story by Andrew Neiderman. When Andrews sat on the front porch, Lillian would place her daughter’s wheelchair behind two conifer trees in the front yard so neighbours or passers-by would not see her. “[Lillian] didn’t want people looking at her,” according to the cousin.

Neiderman claimed that Lillian was so embarrassed by her daughter’s disability that she made sure that whenever Andrews was out in public, she always wore clothes that covered up her wheelchair in a way that would hide her disability from others.

“She was trapped,” said Neiderman. Like the children in Flowers in the Attic, “her mother kept her under lock and key. Firstly, because she was ashamed of her for being disabled, and secondly, because she couldn’t handle [Andrews’ disability].

“Her mother would lock her in her room and not give her dinner, if she got angry at her,” according to Neiderman. “She controlled who Virginia could see, what she could do, and punished her for not doing what she wanted.”

While she was controlled by her mother, Andrews did complete a four-year correspondence course from her home. She soon became a successful commercial artist, illustrator and portrait painter and, after her father’s death in 1957, she used her art commissions to support the family. However, after her husband’s death Lillian reportedly hid her daughter away more than ever: she shopped for her, monitored her visitors and rarely let her out of the house. In fact, Lillian was the one who sold her daughter’s paintings at the local department store.

It wasn’t until her 50s that Andrews began to take control of her life when she turned to writing fiction, channelling her reclusiveness into characters who also lived hidden, secretive lives. Her first novel, written in 1972 and titled Gods of Green Mountain, was a science fiction effort that remained unpublished during her lifetime (it was eventually released as an e-book in 2004). There were other salacious tales that she said she published under a pseudonym. (One sample title of an early unpublished manuscript: I Slept With My Uncle On My Wedding Night.)

Flowers in the Attic: a forbidden fairy tale

Andrews’ breakout novel, Flowers in the Attic, was written in 1975. After she sent her initial manuscript to Simon & Schuster for review, the publisher returned it with the suggestion that she “spice up” and expand the story. In later interviews, Andrews claims to have made the necessary revisions in a single night, although this statement is widely recognized as a fabrication.

When Flowers in the Attic was eventually published in 1979, it was an instant success, reaching the top of the bestseller lists in only two weeks. With its blend of gothic melodrama, Victorian tropes and controversial subject matter, it shocked critics and captivated readers, selling over 40 million copies globally to date. Fame followed almost instantly after the book’s publication, and at the age of 57 Andrews became one of the most famous authors in the world.

For those in need of a refresher, Flowers in the Attic follows the beautiful and doomed Dollanganger children – Chris, Cathy, Carrie and Cory – who are locked away in an attic while their mother, Corrine, desperately attempts to reclaim her inheritance after the children’s father, Christopher, dies in a car accident, leaving Corrine in debt with no means to support them. Because Corrine’s father, Malcolm, is unaware that Corrine had children by her marriage to Christopher, Corrine’s mother, Olivia (called only “the grandmother” in Flowers in the Attic), hides the children in a secluded upstairs room of the enormous Foxworth Hall in Virginia until Corrine can break the news to her father. Corrine assures her four children that they will only be in the room for a few days. Over the next three years, the children use the attic as their playground and face cruel treatment from their ruthless grandmother as their mother supposedly tries to win back the affections of her father. (Spoiler: While the children are locked upstairs, Corrine goes on a European honeymoon with her new husband, Bart Winslow; the elderly Malcom dies unbeknownst to the secluded children; and the grandmother puts rat poison on doughnuts that she then gives to the children, which leads to the death of little Cory. Oh, and Chris and Cathy fall in love.)

The narrative, told from Cathy’s point of view, is a slow descent into psychological horror: betrayal, starvation, poisoned pastries, illness, death, and an incestuous romance between the two eldest siblings.

Though the book was banned multiple times after its initial release, and was often dismissed by critics as sensationalist or even trashy, Flowers in the Attic found something more important: a rabid audience. While Andrews’ novels are not classified by her publisher as “Young Adult,” their young protagonists have made them popular among teenagers for decades. For many readers, especially young women and teens in the ’80s and ’90s, reading Flowers in the Attic became a rite of passage – a battered paperback passed from friend to friend, dog-eared at the “good parts.”

But where did the idea for the story come from?

In her pitch letter to her publisher Simon & Schuster, Andrews claimed that the story behind Flowers in the Attic was “not truly fiction,” leading to long-standing rumours that the novel may have been based on true events. For many years, no evidence was found to support this claim, and the book was passed off as completely fiction. In fact, there was no real explanation for the inspiration until Neiderman released The Woman Beyond the Attic: The V.C. Andrews Story in 2022. In the book, Andrew’s cousin Pat explained that while the future author was undergoing surgery at the University of Virginia hospital for her spine troubles at the age of 17, Andrews became infatuated with a handsome young doctor, who was equally infatuated with her. One day, he told her a shocking story: he and his sisters had spent six years hidden away in one of Charlottesville’s huge mansions to preserve an inheritance. The tale stuck with Andrews for decades and one day she sat in front of a typewriter and made it her own.

Andrews claimed that she wrote Flowers in the Attic in two weeks, combining the doctor’s tale with a dash of fairy tale horror and some of her own experiences (the fire-and-brimstone church her grandfather made them attend in Portsmouth, and her own entrapment after her accident). A virgin, she consulted medical books and her teenage niece to help give the sex scenes in the book their technical and emotional veracity.

Controversy and cult status

Immediately upon its 1979 debut, Flowers in the Attic (which was published by Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster) became an instant bestseller – but not without backlash. It was challenged or banned in schools and libraries across North America because of its incest plot and depictions of child abuse.

There was also the seemingly never-ending criticism from critics. In an interview for Twilight Magazine in 1983, Andrews was questioned about the critics’ response to her work. She answered, “I don’t care what the critics say. I used to, until I found out that most critics are would-be writers who are just jealous because I’m getting published and they aren’t. I also don’t think that anybody cares about what they say. Nor should they care.”

In fact, the controversy and criticism only heightened the book’s appeal, and Flowers in the Attic and its follow-ups flew off the shelves.

What some dismissed as pulp fiction, others read as a metaphor for inherited trauma. Cathy’s journey – from powerless child to vengeful woman (a focus of many of the Dollanganger family series books that followed) – is as much about reclaiming agency as it is about revenge. In an era when mainstream fiction rarely centred complex, angry, sexually autonomous young women, Andrews broke the mould and offered readers something both taboo and, perhaps, cathartic.

Back to the idea of art imitating real life…

Andrews dedicated Flowers in the Attic to her mother, but Lillian – hearing that the bestselling book featured incest – refused to read it, or any of the other novels her daughter would write. Still, she remained a steadfast presence at her daughter’s public events, accompanying her on book tours to France and England, and sitting beside her during all her signings.

In 1981, journalist Stephen Rubin of the Washington Post noticed that during an interview, Andrews “always returns to the subjects that seem to preoccupy her most – her wheelchair and her mother.” When Rubin questioned her about her relationship with her mother, who had been fussing constantly over her throughout the interview, Andrews told him, darkly: “Mothers wear two faces like most people.”

As for her romantic life? Andrews would reportedly flirt with men during her book tours, perhaps trying to make up for the decades that she spent shut away from the world, but her mother’s constant presence made any real relationship impossible. In fact, when the money started rolling in after the initial success of Flowers in the Attic, Andrews bought a house for the two of them in Virginia Beach in 1980. Their co-dependence started rumours – which Andrews fuelled – that the fraught relationship between Cathy and her scheming mother in Flowers in the Attic was based in some truth.

After the attic

Flowers in the Attic was a bona fide success, and readers around the globe wrote letters to Andrews begging for a follow-up. So, she quickly churned out more. The following year, in 1980, Petals on the Wind hit bookshelves, detailing the events immediately after Flowers in the Attic as Chris, Cathy and Carrie travel to Florida after escaping Foxworth Hall. If There Be Thorns followed in 1981, and then Seeds of Yesterday in 1984. She then started working on Garden of Shadows, a prequel to the saga.

“I think I tell a whopping good story. And I don’t drift away from it a great deal into descriptive material,” she stated in 1985 to Douglas E. Winter in Faces of Fear, a book where the author interviewed 17 contemporary British and American horror writers about their life and art. “When I read, if a book doesn’t hold my interest in what’s going to happen next, I put it down and don’t finish it. So I’m not going to let anybody put one of my books down and not finish it. My stuff is a very fast read.”

Ghostwriting from the grave: the Andrew Neiderman era

Tragically, Andrews’ time in the spotlight was brief. She died of breast cancer on December 19, 1986, in Virginia Beach, Virginia, at age 63, only seven years after her debut novel. (Seven years later, her mother, Lillian, passed away in Naples, Florida, where her two sons had set her up in a house with a caretaker.)

At the time of Andrews’ death, she had fully completed and published seven books credited to her name: Flowers in the Attic, Petals on the Wind, If There Be Thorns and Seeds of Yesterday, as well as My Sweet Audrina from The Audrina Series and finally Heaven, and Dark Angel from the Casteel Family Series. She also had written outlines for several other future books and series.

But the demand for her stories was insatiable.

At the time of Andrews’ death, she was working on her fifth “Flowers” book – the prequel Garden of Shadows – and her publisher asked Andrew Neiderman, a gothic novelist in his own right (he penned The Devil’s Advocate), if he could finish it. So, with the family’s approval, Neiderman did. Then, with permission from the Andrews estate, he continued writing novels under her name. A lot of them. Neiderman has now written more than 80 novels under Andrews’ name – transforming V.C. Andrews into not just a person, but a brand. He even fittingly penned the above-mentioned Andrews’ biography.

Thanks to Neiderman, the Dollanganger family series is now an 11-book series that includes: Flowers in the Attic(1979), Petals on the Wind (1980), If There Be Thorns (1981), Seeds of Yesterday (1984), Garden of Shadows (1986), Christopher’s Diary: Secrets of Foxworth (2014), Christopher’s Diary: Echoes of Dollanganger (2015), Secret Brother(2015), Beneath the Attic (2019), Out of the Attic (2020) and The Shadows of Foxworth (2020).

That’s not to mention the multiple other series written entirely by Neiderman, of which there are dozens. All new “V.C. Andrews” work published subsequent to 1988, while credited solely to Andrews, is the work of Neiderman, under licence from the V.C. Andrews estate.

While purists argue that nothing compares to the haunting lyricism of Andrews’ original voice, Neiderman-era books have expanded her legacy to include dozens of sagas across generations and geographies, almost all of them featuring classic Andrews tropes: domineering matriarchs, hidden siblings, traumatic secrets and lavish decaying mansions.

Pop culture resurrection: from paperbacks to Lifetime

Flowers in the Attic made the jump to the big screen with a 1987 film directed by Jeffrey Bloom and starring Louise Fletcher, Victoria Tennant, Kristy Swanson and Jeb Stuart Adams. Though it was released after her death, Andrews was involved in the film. She demanded, and eventually received, script approval and even appears in the film, uncredited, as the window-washing maid that the children encounter towards the end of the film.

Bloom’s original early cut of the movie, which was screened to a test audience in December 1986 in San Fernando Valley, was met with negative reactions, mostly because of the scenes of incest between Chris and Cathy. The outrage is peculiar in retrospect…because incest is, like it or not, at least part of the reason for the book’s success. Regardless, the studio brought in an unknown director to film the new ending after Bloom refused to re-shoot, and the film was severely re-cut.

The revamped Flowers in the Attic opened in theatres across North America on November 20, 1987, and received mostly negative reviews from critics and fans of the book, who both disliked the film’s slow pacing, acting and, most of all… drastic plot changes.

The film has been a point of contention among Andrews’ fans for decades.

In the 2010s, a new generation rediscovered the Dollanganger saga when Lifetime announced that it was adapting the original Dollanganger family series into a series of made-for-TV films, and committed to stay loyal to the original source material. “It’s faithful,” executive producer Michele Weiss told The Hollywood Reporter in 2014, just days before Flowers in the Attic (starring Kiernan Shipka, Heather Graham and Ellen Burstyn) aired on January 18, 2014. “We tried to be very true to the plot of the book although we had to add some stuff in because it’s a movie, it’s all about action.”

Though slightly tamer than the books, the Flowers in the Attic adaptation retained the gothic visuals and familial dysfunction that defined the book. It was also a made-for-TV hit, and subsequently Lifetime released an adaptation of Petals on the Wind, which premiered on May 26, 2014. Two more adaptations from the series, If There Be Thorns and Seeds of Yesterday, both aired in 2015.

The Lifetime network continued its association with books by (and inspired by) author V.C. Andrews with a new four-part limited series, Flowers in the Attic: The Origin in 2022, which was based on the prequel book Garden of Shadows. (There is some dispute over whether this particular novel was written in part by Andrews before she died, or whether it was written entirely by Neiderman.)

More recently, the V.C. Andrews cinematic universe has expanded with miniseries based on other Andrews books – including the Landry and Casteel series – drawing in fans of campy, bingeable family drama. Think Succession meets The Secret Garden meets American Horror Story: Gothic South Edition.

Meanwhile, her novels – some long out of print – have enjoyed a resurgence among nostalgic millennials and TikTok-era readers who trade annotations and gasp over plot twists as if they’re discovering them for the first time.

The feminine grotesque: Why she still matters

Andrews’ stories have endured through the decades not just because of their plot twists or their shock factor, but because they tap into something elemental: the strange, stifling experience of being a girl in a world obsessed with beauty and obedience.

Her heroines are almost always caged birds, dolls in glass cases, ballerinas with bruised feet. They are at once fragile and feral: angels with teeth.

In a literary landscape where the gothic is being reclaimed and re-examined – by authors such as American author Carmen Maria Machado, Canadian author Silvia Moreno-Garcia and American author Ottessa Moshfegh – Andrews’ legacy feels more relevant than ever. Her work was one of the earliest popularizations of what we might now call “the feminine grotesque”: narratives that acknowledge the rage, desire and rebellion living beneath the surface of girlhood.

Final petal

Today, V.C. Andrews is both a real woman and a literary myth…one of the most popular authors of all time. She’s the grandmother of modern gothic melodrama, the woman behind the locked attic door. Whether you discovered her in the bookstore or at the library as a teenager, through a guilty-pleasure Lifetime marathon or via a viral TikTok rant about Petals on the Wind (Cathy does WHAT?!), one thing remains clear: no one does beautiful, twisted family secrets quite like Andrews. And just like the attic, her stories are dark, strange, and impossible to turn away from.

“Yes, Virginia Andrews had a difficult life,” says Neiderman. “But the thing about her is: she overcame it all – and went on to have one of the biggest successes of commercial fiction.”