Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

When you think of iconic royal wedding dresses, some gowns probably come to mind instantly. Maybe you remember the elaborate ivory silk taffeta and antique lace gown designed by David and Elizabeth Emanuel and worn by Diana, Princess Of Wales, in 1981; or maybe it’s the impeccable long-sleeved lace and silk gown designed by Sarah Burton for Alexander McQueen that was worn by Kate Middleton in 2011; or even the sophisticated boat neck gown designed by Clare Waight Keller for Givenchy worn by Meghan Markle in 2018. But one royal wedding dress made an even bigger statement: the royal wedding dress worn by the ever-stylish Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) at her wedding to the dashing naval officer Philip Mountbatten, Duke of Edinburgh, on November 20, 1947, at Westminster Abbey. Designed by Norman Hartnell, the stunning gown has the most remarkable story behind it – starting with the fact that given the rationing of clothing at the time, the then-Princess Elizabeth had to purchase the material for her wedding gown using ration coupons.

Queen Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning monarch in British history, died at her Balmoral estate on September 8, 2022. She was 96 years old. In tribute to Her Majesty the Queen, we take a look back at the wedding everyone was waiting for in post-World War II Britain and the moving story of her satin with tulle wedding dress, which helped bring joy and unity to a nation.

Young love

Princess Elizabeth of England and Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark first met at the Britannia Royal Naval College in July 1939, when Elizabeth was 13 and Philip was an 18-year-old cadet. The two began to exchange letters as Philip served with the Royal Navy in combat in the Mediterranean and the Pacific from 1940 until the end of World War II. Upon his return in 1946, their relationship blossomed, with Elizabeth saying that she had fallen in love with the young naval officer. On February 28, 1947, Philip became a British subject, renouncing his right to the Greek and Danish thrones and taking his mother’s surname, Mountbatten. It’s presumed that he proposed in June that year, on the grounds of Balmoral, and the couple’s engagement was officially announced on July 9, 1947. Elizabeth was 21.

“To have been spared in the war and seen victory, to have been given the chance to rest and to readjust myself, to have fallen in love completely and unreservedly makes all one’s personal and even the world’s troubles seem small and petty,” Philip wrote in one of his letters in 1946, according to Vogue.

Rationing

At the time of their engagement, the war had been over for two years but the British government was still recovering and millions of Britons were living in the aftermath of bomb-damaged cities. Rationing was in effect for everyone, including the Royal family, and following her engagement, the future Queen began saving clothing coupons to purchase the materials needed for her wedding dress. In recognition of the morale boost that the upcoming nuptials would give the country, Elizabeth was granted 200 extra ration coupons from the government for the fast-approaching celebration.

As excitement began to build across the country, Elizabeth received hundreds of clothing coupons from everyday citizens from across the country to help her purchase the scarce (and expensive) materials needed to bring her gown to life. It was a touching show of support for Elizabeth and the monarchy. However, each ration coupon was returned to the sender with a thank-you note, as it was illegal to transfer them, and the princess was determined to make her post-war budget work.

The dress

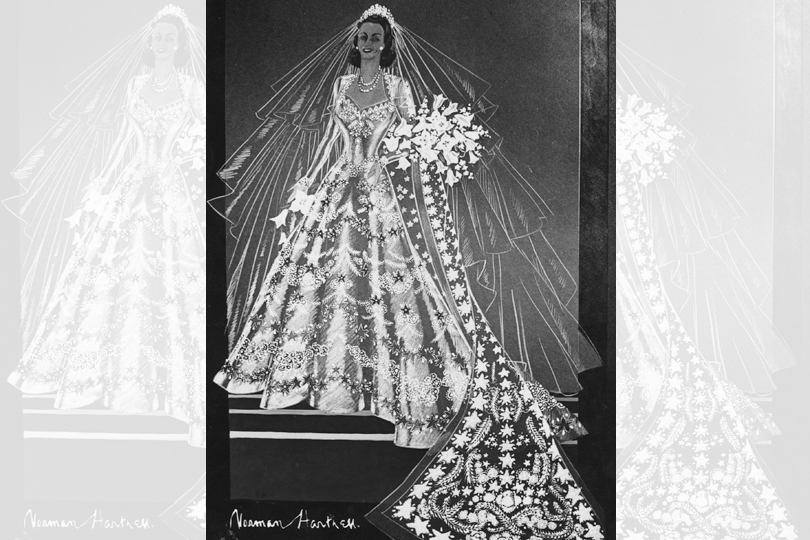

Elizabeth’s royal wedding dress was designed by British couturier Sir Norman Hartnell (1901–1979), whose designs were generally romantic in their sensibility, featuring lots of embroidery. Hartnell, who was actively designing for the Royal family, was commanded by the Queen to design her daughter Elizabeth’s wedding dress, and later recalled that he set out to produce “the most beautiful dress I had so far made” for the nuptials.

The timeline was quick. In fact, according to the Royal Collection Trust, Elizabeth’s gown wasn’t even started until August 1947 – less than three months before her November nuptials.

It took the hard work of 350 women to pull off creating the intricately detailed piece in such a short time frame, and they were all sworn to secrecy to protect any details about the dress from leaking to the press. The dress’s final design was kept secret, although much speculation surrounded it.

Betty Foster, a then-18-year-old seamstress who worked on the gown in Hartnell’s London studio, told the Telegraph in 2007 that “Americans had rented the flat opposite to see if they could get a glimpse of the dress, and that [Hartnell] had to cover the workroom windows with whitewash and muslin to stop snoopers.”

According to the Royal Collection Trust, one of Hartnell’s inspirations for Elizabeth’s wedding gown was Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli’s “Primavera,” which was made in the late 1470s or early 1480s (datings vary). Hartnell hoped the wedding dress, like the painting, would symbolize “rebirth and growth” in Britain after the war. The word “primavera” means spring in Italian, and the painting features Flora, the goddess of spring, and Venus, the goddess of love and beauty: a perfect way to combine the new beginning of a wedding and also a fresh start after the war.

As for the dress itself: it featured a high fashionable sweetheart neckline, tailored bodice, long tight sleeves, full skirt and a beautiful 15-foot star-patterned train. It was made from ivory silk and satin that had been produced in Britain (including Lullingstone Castle in Kent, and Dunfermline in Scotland). Interestingly, the palace had to reassure the public at the time that the silkworms had come from China, and not from one of the countries Great Britain had fought in the war, like Japan or Italy.

The pricey fabric had been especially difficult to acquire at the time, as bridesmaid (and Philip’s cousin) Lady Pamela Hicks told People.

“Tulle could easily be acquired, whereas duchess satin was so difficult to get in those days,” she said, adding that the bridesmaids wore tulle dresses while the princess’s gown was made of satin with tulle accents.

The wedding gown was also covered in an astonishing 10,000 seed pearls that had been imported from America, all hand-sewn onto the gown in a floral pattern. There were also intricate crystal embroidered flower and leaf motifs throughout, much like the floral-trimmed dresses in Botticelli’s famous painting. According to Hartnell, “the motifs had to be assembled in a design proportioned like a florist’s bouquet.” And, unknown to the princess, Hartnell added a good luck charm. Amid floral emblems signifying the nations of the UK and the countries of the Commonwealth, he added an extra four-leaf shamrock on the left side of the skirt so that her hand could rest upon it during the ceremony.

The big day

Although members of the Royal family obviously have wedding dress fittings like other brides-to-be, it turns out Elizabeth didn’t actually have one, and so no one knew if her gown would fit properly until the morning she got married.

Foster, the aforementioned seamstress, told the Telegraph that Elizabeth’s gown was delivered to her on the wedding day, “respecting the tradition that it would be unlucky” to try it on beforehand.

Thankfully, it fit.

On the big day, Elizabeth did her own makeup. She paired Hartnell’s gown with a pair of satin heels trimmed with silver and seed pearl that had been made by Edward Rayne. Elizabeth’s father, King George VI, gave her a wedding present of a pair of pearl necklaces that had once belonged to two English queens from the 17th and 18th centuries, and the diamond and pearl cluster earrings that she wore were also family heirlooms, passed down from her great-grandmother. On her head, she wore a silk tulle veil held in place by a diamond fringe tiara that she had borrowed from her mother, Queen Elizabeth (later known as the Queen Mother).

Adding a little drama to the wedding day, the tiara broke as Elizabeth was getting ready for the ceremony; a royal jeweller was brought in immediately to make the repairs so Elizabeth could wear it to the ceremony.

Her wedding bouquet consisted of white orchids with a sprig of myrtle that was taken from “the bush grown from the original myrtle in Queen Victoria’s wedding bouquet.” The bouquet was returned to Westminster Abbey the day after the service so it could be laid on the tomb of the Unknown Warrior, following a tradition started by Elizabeth’s mother at her own wedding in 1923.

Elizabeth and Philip were married at 11:30 am GMT on November 20, 1947, at Westminster Abbey, in front of 2,000 people. (The ceremony was recorded and broadcast by BBC Radio to 200 million people around the world.) The wedding was the first major celebratory event since the end of the war, and both the service and Elizabeth’s beautiful dress served as an escape from post-World War II austerity in the UK.

“I had forgotten how beautiful it was, with that exquisite train – and how small the princess was,” Betty Foster, the seamstress who had worked on the dress, told the Telegraph after viewing the gown, which was on display at Buckingham Palace back in 2007.

“On my way home from the wedding celebration, I remember everyone on the train was talking about the dress, and I felt so proud to have worked on it.”

Hartnell worked closely with Elizabeth and continued to design clothes for her for a number of years before his death in 1979. He designed some of her most important looks, including her 1953 Coronation dress, which mimicked her wedding dress neckline and skirt, and countless ensembles that she wore on her overseas tours. Hartnell more than earned his Royal Warrant. In recent years, his work has been a large part of royal exhibits featuring the Queen’s clothing. And, most recently, Princess Beatrice wore a vintage Norman Hartnell gown borrowed from her grandmother the Queen for her own wedding to Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi on July 17, 2020. “It was an honour to wear my grandmother’s beautiful dress on my wedding day,” Beatrice said on Twitter.

After the wedding

The young couple had been married a mere five years when King George VI fell ill, then grew sicker and died on February 6, 1952. In an instant, Princess Elizabeth became Queen, and Philip became Consort. At the Queen’s coronation on June 2, 1953, he knelt before her and swore to be her “liege man of life and limb.”

Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip’s relationship was one of love, respect and long-lasting admiration. Although the couple had their fair share of very public ups and downs throughout their marriage, their connection was one-of-a-kind. Together, they shared sons Charles (now King Charles III), Prince Andrew, Prince Edward and Princess Anne.

On November 20, 1997, the night of her 50th wedding anniversary, Queen Elizabeth made a speech at London’s Banqueting House in front of Tony Blair, the longest-serving Labour prime minister of Great Britain, and dozens of distinguished guests. It was relatively short and succinct, as her speeches usually were, but ended with Elizabeth praising her husband with a profound and heartwarming tribute:

“He is someone who doesn’t take easily to compliments but he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years, and I, and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know.”

Twenty-four years later, the Royal family announced that Prince Philip had passed away peacefully at the age of 99 on the morning of April 9 at Windsor Castle. On September 8, 2022, Queen Elizabeth would follow.

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.