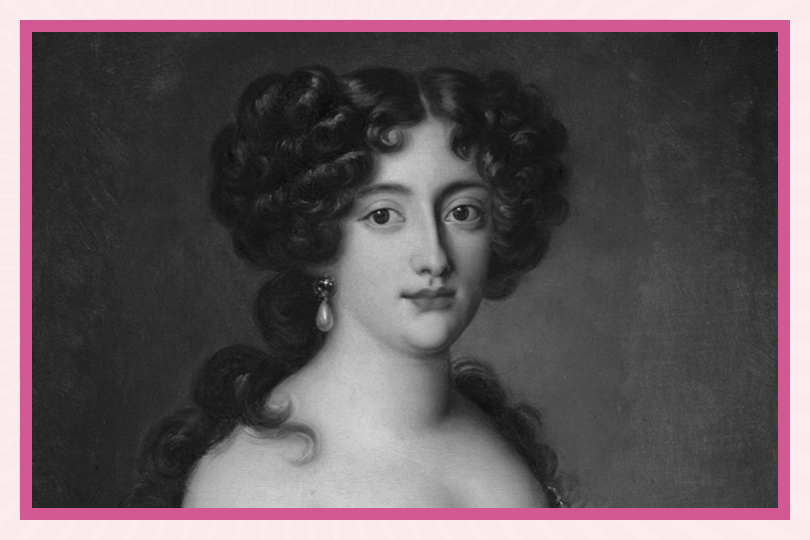

On New Year’s Eve in 1675, a cavalier in ragged men’s apparel rode into London. The mud-covered, weather-beaten figure was at first mistaken for a postman, but the rider’s beauty and elegance gave her away: it was Hortense Mancini, the legendary Duchess Mazarin, who had fled her cruel husband and had been on the run across Europe. The scandal mongers adored her, and her every move was watched by seventeenth-century gossip columnists. As the English diarist John Evelyn famously noted, “all the world knew her story.”

During the last two decades of her life in England, the Italian-born, French-bred woman went on to establish a legendary salon of artists and intellectuals at her London residence and went down in history as one of the mistresses of the pleasure-seeking Merry Monarch himself, King Charles II. But how did she come to this point in her life, in England at the age of 29 years old? Without further ado, here is a look at the life and legacy of the scandalous and sympathetic Duchess Mazarin, who became an icon for women seeking legal separation from their husbands.

The early years

In 1646, Hortense Mancini was born to Roman nobleman Lorenzo Mancini and Hieronyma Mazzarini, the sister of the powerful Cardinal of Mazarin, the first minister of the French King Louis XIV. As described by her biographer Elizabeth C. Goldsmith, the Cardinal invited Hortense and her four sisters and two cousins to live at the Palais Mazarin in Paris, to be brought up at the French court. Instantly celebrated for their beauty and lively demeanors, they become known as the charming Mazarinettes.

Hortense, the second youngest of the group, later described her fairy-tale childhood at the centre of the French royal court, where she had access to a good education and regularly mingled with the young coming-of-age Louis XIV himself (in fact, her older sister Marie was famously his first love, before he was forced into a royal marriage himself and they were torn apart).

But the fairy tale didn’t last long. One by one, the girls were married off in strategic alliances to fortify their uncle’s political position. The Cardinal developed a particular fondness for little Hortense and decided to name her as the heir to his massive fortune, and so her marriage held particular importance.

To his later regret, Mazarin rejected an offer from the young English exile, Charles Stuart, because at the time he was just a penniless royal fighting to regain the throne his father had lost in the Civil War. Marriage negotiations with the Duke of Savoy and the Duke of Lorraine both fell through as well.

Right before his death in 1661, Mazarin hastily arranged a marriage for 14-year-old Hortense with 29-year-old military man Armond-Charles de la Porte, Duc de la Meilleraye.

Duchess Mazarin

After her uncle’s death and her marriage, Hortense and Armand-Charles took on the titles of Duc and Duchess of Mazarin. According to Goldsmith, “they were positioned squarely at the center of the most favored social circles in the city and at court,” their residence being in the cardinal’s sumptuous Mazarin palace, near the Louvre.

They could have had a happy life.

But unfortunately, it was a match made in hell. Armand-Charles turned out to be a religious extremist and a deeply jealous man—definitely not the right fit for the young, party-loving, flirtatious, intelligent, and beautiful Hortense. He insisted on travelling around his lands, with Hortense, even when she was very pregnant. (Together, they had three daughters and a son.) Armand-Charles became more and more possessive of her as the years went on, forcefully confining her to palaces and convents, and moving her whenever she made friends or began to enjoy herself.

On the run

By 1666, Hortense began the long process of trying to obtain a legal separation from her husband–a quest that would last a lifetime.

By 1668, she was, according to an essay by Claudine van Hensbergen, “stretched to the limits of marital obedience” and she fled into exile, disguised in men’s clothing, leaving her children behind. She went to Italy for a few years, for a time living with her older sister Marie, who was then the Duchess Colonna in Rome, then to Savoy, where she found refuge with her former suitor, the Duke of Savoy, who it was rumoured became her lover. Hortense was able to secure a pension from Louis XIV and lived at the Chateau Chambery for another few years.

It was in this period that she wrote and published her memoirs. Scholar Courtney Beggs credits Hortense as the first woman in France to publish a memoir in her lifetime. And according to Sarah Nelson, who edited and translated a recent publication of the memoir, Hortense undertook the writing of her life story as a maneuver to win the right to live independently, determining her own destiny by defining her public image.

Her memoir was widely read at the time and increased her already notorious reputation as a scandalous woman, but also as a sympathetic victim of her husband. In the meantime, she continued to pursue legal means to gain freedom from her husband and to be granted enough money to live independently.

Unfortunately, the Duke of Savoy died in 1675 and Hortense needed a new home.

She looked across the waters to England. There, King Charles II sat on the throne (the suitor her uncle had, perhaps short-sightedly, rejected), and one of her Italian-born cousins, Maria Beatrice d’Este (known as Mary of Modena in England) and her husband Prince James, the king’s younger brother and heir, granted her support and lodgings.

Hostess and Royal Mistress

Hortense instantly made her mark in England. She brought the French tradition of salons (in which women presided over esteemed gatherings of the time’s movers and shakers) over to London. Her residence became, according to Beggs, “one of the most famous intellectual and literary salons of the Restoration.”

Furthermore, Charles, who had sought her hand all those years ago when she was still a young girl, was intrigued by the daring 29-year-old woman who had travelled Europe, often disguised as a man.

It wasn’t long before she joined the ranks of his famous royal “harem,” where English actress Nell Gwynn and French aristocratic Louise de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, currently reigned supreme. Hortense was quickly added to the royal payroll, and Charles could often be found with his new mistress.

For a time, Hortense succeeded in replacing Louise as Charles’ principal mistress—in fact, her presence in England had been encouraged by a political faction of men eager to redirect power away from Louise, who was thought to be a French spy for Louis XIV; they hoped she would take her place. And she did, for a time.

The later years and legacy

She might have maintained her position as Charles’ mistress, but for her own promiscuity–with both other men and women.

A liaison with the visiting Prince of Monaco, and a scandalous, very public affair with Anne, Countess of Sussex (the illegitimate teenage daughter of Charles himself through one of his earlier mistresses), cooled their relationship and Charles temporarily cut off his support.

While they never resumed their affair, they remained close friends until his death in 1685.

When Prince James and Hortense’s cousin Mary were crowned King and Queen of England, Hortense continued to live in England at the centre of the political world and as an influential hostess. Even after James and Mary lost their crowns in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and fled into exile to Paris (where Armond-Charles was still fighting in the courts to force his wife to return to him) Hortense stayed in London, far away from her husband’s reach.

In her later years, her salon became known as a centre for gambling and eventually her drinking habits dangerously increased. She began to lose the beauty she had relied on and she became increasingly lonely, save for a close friend she had in fellow exile and intellectual Charles de Saint-Evremond. According to Denys Potts, who researched Hortense’s later life, in November 1699 she “drank herself to death in what was widely perceived as an act of suicide,” having “finally given up the struggle to survive in a world in which the conditions were always dictated by men.”

In the end, Armand-Charles finally succeeded in regaining possession of his wife—not in the way he had wanted, but he made the most of it. According to Nelson, Armand-Charles had her remains shipped to him in France, and for a year he paraded across France to his various lands, bringing his wife in her coffin along with him like a trophy.

Though she did not succeed in gaining a legal separation from her husband like she wished, she managed to carve out a place for herself on the run and left a lasting legacy through her memoir. As noted by her biographer, “in her bold roles as writer, traveler, salonniere, gambler, and runaway wife, Hortense Mazarin became a cultural icon.” Ultimately, her memoir and her divorce trials became important steps in the long process of redefining marriage rights for women.