Part of an ongoing series of 29Secrets stories, taking a deep dive into the history of legendary beauty products and iconic fashion and pop culture moments…

By Christopher Turner

Illustration by Michael Hak

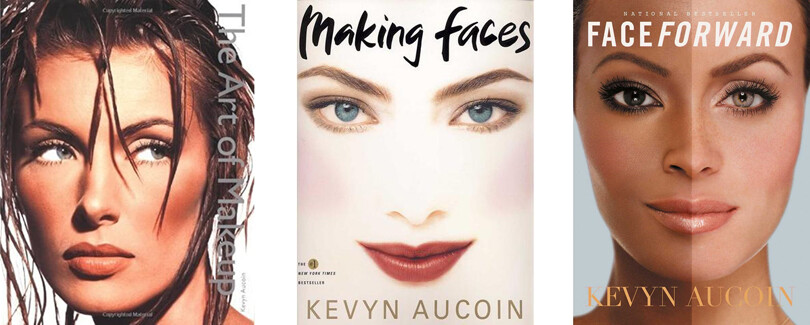

Throughout his short career, Kevyn Aucoin painted the faces of some of the world’s most famous women, worked on countless fashion magazine covers, and authored three bestselling books on beauty (The Art of Makeup in 1994, Making Faces in 1997 and Face Forward in 2000) – all of which earned him the nickname the “Michelangelo of maquillage.” As the makeup artist wholly responsible for the “sculpted” look of many celebrities and top models, and for introducing makeup contouring to the general public, he truly changed the beauty industry.

Described by friends and celebrities as “teddy bear-like,” the 6-foot, 4-inch Aucoin was outspoken about diversity, gay rights, gun control and race relations. In October 2000, two years before his death, he told Time magazine, “If all it says on my gravestone is ‘DID GOOD LIPSTICK,’ I’d rather it say nothing at all.”

His story is inspiring, and heartbreaking. Read on for more on the most celebrated makeup artist of his time.

Valentine’s Day baby

The day Aucoin was born in Shreveport, Louisiana – February 14, 1962 – “was my best Valentine ever,” recalled Thelma Aucoin, who adopted him one month later. He was the first of four children the Aucoins adopted because they could not have biological children.

Aucoin often said he knew he was gay from the age of six. In The Art of Makeup, he wrote that his mother “even let me buy a pair of lime-green, patent-leather penny loafers with gold buckles.” He wore them to school every day – until his father found them and threw them away.

As a child, he was effeminate, loved Vogue magazine and all fashion magazines, blasted Barbra Streisand and was completely fascinated by makeup. He was relentlessly targeted by bullies for much of his childhood but, despite this adversity, his passion for makeup always prevailed. He borrowed makeup artist Way Bandy’s 1977 instruction manual entitled Designing Your Face: An Illustrated Guide to Cosmetics from the local public library (failing to ever return it), and increasingly saw physical transformation through makeup as his way out of small-town life, once saying: “If I could just make things look better, things would be better.”

Aucoin started stealing makeup from local stores, as he was too embarrassed to buy. Then he would then spend hours practising makeup application techniques and transforming his younger sister Carla to look like a model (he gave his first makeover when he was 11 and she was five). At age 15, he dropped out of high school after two classmates tried to run him over with a car. Shortly after, he enrolled in cosmetology school – and it wasn’t long before he surpassed his teacher’s abilities and began teaching the classes himself.

Perhaps it was his perception of his own appearance that made Aucoin such an empathetic makeup artist. “I got called ugly most of my childhood,” he would later say. “I was told I was ugly constantly.”

Bright lights, big city

In 1982, Aucoin met Jed Root, with whom he moved first to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and then on to New York City. Hoping to get noticed, Aucoin did pro bono makeup on models for test shoots (one of his early canvasses was ’80s supermodel Paulina Porizkova). His most daring stunt to get noticed was arguably when he dressed Root as his agent in a suit from the Salvation Army, and the two of them brought his portfolio to the offices of Vogue. “He would just plant himself in front of me,” recalled Linda Wells, an editorial assistant at Vogue’s beauty department at the time. “He was more passionate and more obsessed than any other person I’ve met in my life.”

Eight months after moving to Manhattan (where he spent his first winter in an unheated Hell’s Kitchen walk-up), Aucoin got his big break when he was booked to do Meg Tilly’s makeup for a spread in Vogue, which would be shot by acclaimed fashion photographer Steven Meisel.

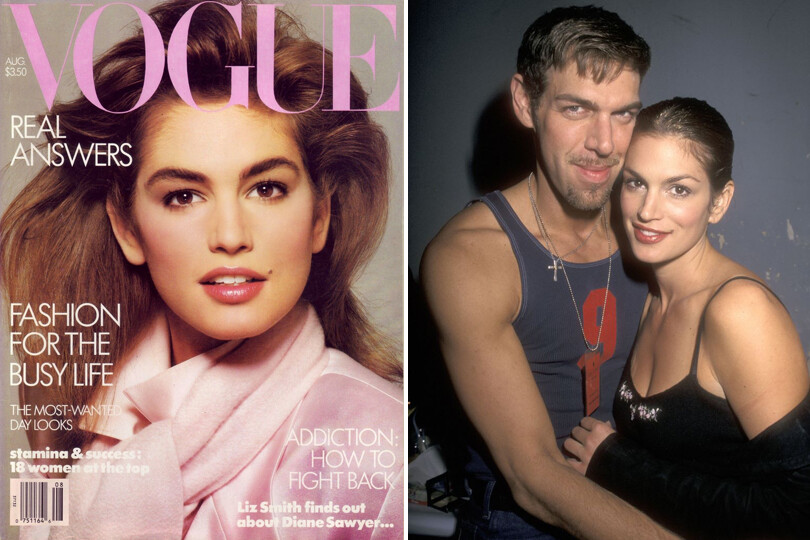

In 1986, Vogue’s sittings editor Polly Mellen booked him for a cover shoot that would be shot by the legendary fashion photographer Richard Avedon. The virtually unknown model was young, with bombshell brunette hair, pillowy lips, and what was to become her signature beauty mark…a young Cindy Crawford. This cover – and, more specifically, Crawford’s meticulously painted face – pushed Aucoin’s career into gear.

“It was such a big deal for both of us. We worked together a lot after that. If I worked five days in a week, three or four of them were with Kevyn,” Crawford recalled years later.

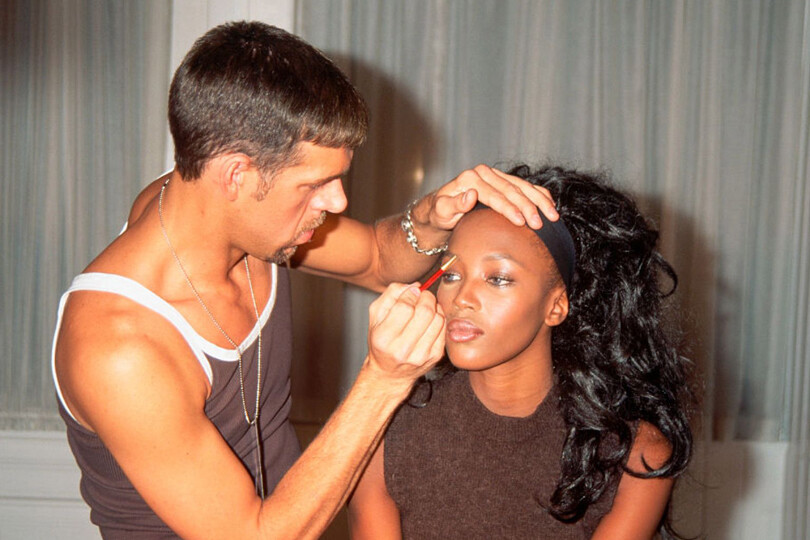

Over the next three years, Aucoin did the makeup for 18 American Vogue covers as well as numerous covers for other fashion magazines, including Harper’s Bazaar and Cosmopolitan. In fact, between 1987 and 1989, he did nine Vogue covers in a row as well as seven Cosmopolitan covers. He was part of a movement that pushed fashion into the mainstream in the early 1990s, and it was Aucoin who changed the way high-profile models did their makeup, ultimately transforming Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, Christy Turlington, Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista and Paulina Porizkova into supermodels and cultural icons.

“I was not going to go to any other person but Kevyn’s chair,” Campbell said of working with him, adding that he was the only makeup artist in town who understood Black skin. Of collaborating with Aucoin on shoots with photographers Steven Meisel, Irving Penn and Francesco Scavullo, Evangelista explained: “Magic didn’t happen on the set – it happened in the dressing room, in front of the mirror, with Kevyn.”

It wasn’t just the supermodels who had Aucoin on speed dial. As he began to divide his time between New York and Los Angeles, he quickly grew a celebrity client roster that included Madonna, Cher, Courtney Love, Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Gwyneth Paltrow, Liza Minnelli, Isabella Rossellini, Sarah Jessica Parker, Barbra Streisand and Tina Turner. He almost single-handedly created the category of celebrity makeup artist.

“Kevyn was ahead of his time – [he] somehow gravitated toward celebrities,” explained famed hairstylist Orlando Pita of the makeup artist’s game-changing instinct to build relationships with Hollywood icons and pioneer the industry’s red-carpet culture.

By the mid-’90s, Aucoin dominated the beauty industry and had become a household name – all before he ever had a namesake brand, which he eventually launched in 2001.

Cher once recalled walking into beauty store Make Up For Ever with Aucoin: “It was like Brad Pitt walked in.”

At his peak, he would often be booked months in advance, and he could command as much as $6,000 for a single makeup session.

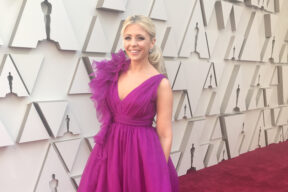

He appeared in countless interviews on The Oprah Winfrey Show, made regular appearances on CNN and MTV, and could be spotted backstage at the Academy Awards. Years later, he played himself in Zoolander (2001) and the infamous Sex And The City fashion show episode where Carrie falls on the runway.

Changing faces, starting trends and the introduction of contouring

Aucoin’s legacy was his ability to changes faces with makeup and usher in some of the biggest beauty trends of the 1990s. One example: it was Aucoin who revived the 1920s pencil-thin eyebrow trend (made famous by Marlene Dietrich, Carole Lombard and Joan Crawford), when he rebelled against the minimalist grunge trend and plucked the brows of a host of supermodels at an Isaac Mizrahi runway show in the ’90s. “He decided that everyone needed to look like Carole Lombard and have really skinny eyebrows,” said Mizrahi. It was a radical move – Cindy Crawford’s agent threatened to sue. “It was a real crisis for her career,” Mizrahi recalled. “But then she started getting more jobs because she had skinny eyebrows. Then everybody started tweezing their eyebrows! Kevyn invented so many things that we look at today as just stuff that exists. He was a completely brilliant experimental risk-taker.”

Skinny brows weren’t the only one of Aucoin’s moves to change the face of fashion: he was also a pioneer of the makeup tutorial. Today, YouTube and Instagram are filled with countless makeup artists sharing their tips on how to get the perfect smoky eye, but before the internet Aucoin was really the only one sharing his wisdom. After years of high-profile Voguecovers, runway shows and endless editorial shoots, he released a series of coffee table books, each sharing his makeup tips and tricks. In the first, 1994’s The Art of Makeup, Aucoin used only his brushes to turn a 50-something Martha Stewart into a dead ringer for 1940s femme fatale Veronica Lake, and transformed his own 66-year-old mother into Marlene Dietrich. “This was the first time that you really saw those kind of makeover books,” according to makeup artist Lisa Eldridge. “The transformations were mind-blowing.”

But, ultimately, Aucoin’s legacy will be taking makeup sculpting mainstream and introducing makeup contouring to the everyday woman.

Long before YouTube makeup tutorials showed how to use light and dark pencils to accentuate shadows and highlights, and long before Kim Kardashian started selling contour kits to the masses, Aucoin was blending backstage, using lines to thin out a nose or boost the cheekbone. Then, in his most popular book, 1997’s Making Faces, he began to show readers how to contour, and displayed the techniques needed to create different looks. There’s a reason why it’s often referred to as the beauty bible.

But Aucoin didn’t stop there. In October 2000, he published his industry-defining cosmetics book, Face Forward, which became a New York Times bestseller. The book was widely noted for introducing makeup sculpting and contouring to the general public.

Kardashian’s makeup artist Mario Dedivanovic, who these days is regularly credited as the king of contouring, defers to Aucoin…rightfully so. “Kevyn was the first one to put that out for the world to see,” he says.

Aucoin was also one of the first makeup artists to champion diversity in the beauty industry, starting in 1983 when he was made a creative director at Revlon and pushed to create a line of foundations called The Nakeds. It was a revolutionary moment in makeup as the shades in this line catered to all skin tones, something that wasn’t the norm.

In the years that followed, he was courted by MAC, Vincent Longo, Laura Mercier and Shiseido to collaborate.

In 2001, he launched his own makeup collection, Kevyn Aucoin Beauty. Many of the products in the collection have since achieved cult status: in fact, his Sensual Skin Enhancer, Neo-Highlighter and Sculpting Contour Powder are still sell-out products in today’s saturated markets.

He anticipated 24/7 social media

One of the most interesting things about Aucoin was his compulsion to document his every move. He was obsessed with a constant self-documentation: his daily video diaries, a habit that began in his teens, ranged from staged skits and mockumentary news videos to behind-the-scenes footage of his makeup sessions with the world’s most famous women. He recorded and kept everything, including answering machine cassettes and videotapes, and created meticulous scrapbook collages of his Polaroids, appointment book pages and notes.

In 2018, years after his death, a feature documentary titled Larger Than Life: The Kevyn Aucoin Story hit screens, chronicling the extraordinary life of the first celebrity makeup artist. Directed by Tiffany Bartok, the film relied heavily on Aucoin’s detailed video diaries, complemented by countless celebrity interviews singing his praises.

“Maybe this film is the point, but when Kevyn was shooting [his daily video diaries], who knows what he was thinking? He was just documenting, documenting, documenting…. It is like a time capsule to be able to look back and see those moments…what kids we all were,” Cindy Crawford reflects in the documentary.

His death

Aucoin’s tragic death in May 2002 was at first attributed to a metabolic disorder, but shortly afterwards details began to surface that suggested it was actually a severe addiction to painkillers that killed him. That was later confirmed by a coroner’s ruling.

In September 2001, after having increasing amounts of back pain and headaches, Aucoin was diagnosed with a tumour on his pituitary gland. He had been suffering for much of his life from acromegaly because of this tumour, but it had gone undiagnosed. The tumour meant that the brain continued secreting growth hormones long after his teenage years. In fact, during the last five years of his life, Aucoin grew two inches and went up two shoe sizes. Shortly after his diagnosis, he underwent a successful surgery and had the tumour removed, but he continued to experience pain. To ease his physical and mental suffering, he began taking increasing amounts of prescription and non-prescription painkillers, including Vicodin, Lorcet, Xanax and Soma.

Aucoin’s partner, Jeremy Antunes (whom he began dating in 1999, married in an unofficial ceremony in Hawaii in 2000 and thereafter referred to as his husband), implored Aucoin to get help. But while Aucoin tried to recover, he could not entirely stop his drug use. Antunes went to Paris for a week to be alone, and in that time, Aucoin became ill and was hospitalized at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, New York. He died on May 7, 2002, of kidney and liver failure due to acetaminophen toxicity caused by prescription painkillers.

The fact that Antunes left Aucoin for what became the last week of his life created animosity between Aucoin’s family and Antunes, resulting in Antunes being locked out of the home he shared with Aucoin. Despite Aucoin’s instructions that his ashes be scattered in Hawaii where he was married, the family had his remains buried with his mother in Louisiana.

The beauty and fashion industry was devastated by the loss. The industry also has never seen or celebrated a makeup artist the same way it has Aucoin. Naomi Campbell perhaps put it best when she reflected, “There will never be another Kevyn Aucoin. Never. Never. Never.”

![]()

Want more? You can read other stories from our The Story Of series right here.